They’re surprised when the staff, which knows the history, tells them about the police raid on the original Black Cat and its gay patrons on New Year’s Eve 1967 and the protest that followed six weeks later.

Far from being unlucky, they learn, the Black Cat in Silver Lake is the site of an important moment in the LGBT history of Los Angeles.

Designated a historic and cultural monument by the City of Los Angeles in 2008—just as the passage of Prop 8 was leaving the LGBT community reeling—the building this week was adorned with a plaque that marks the site’s significance. Here’s what it says:

The Black Cat

Site of the first documented LGBT civil rights demonstration in the nation

Held on February 11, 1967

Declared 2008

Historic Cultural Monument No. 939

Cultural Heritage Commission

City of Los Angeles

It was the first time that LGBT people in the United States organized a protest against police persecution. The raid and the arrests that accompanied it inspired the first legal argument that gay people were entitled to equal protection under the law.

“We need a plaque to look at and go to,” said Alexei Romanoff, 77, one of the few known survivors of the 1967 protest that followed the raid. “I want some young person to go and say, ‘That’s where my civil rights started.’ ”

The Black Cat is at 3903 Sunset Blvd. at Hyperion Avenue. In the late 1960s it was one of a dozen gay bars along a one-mile stretch of Sunset ending at Sunset Junction.

“Most are beer bars, with pool tables, juke-boxes, coin-operated game machines,” gay activist Jim Highland wrote in a 1967 article in Tangents, a gay magazine published in the late 1960s. “The buildings housing the bars are shabby, the rents cheap, and business failures are common. But when one bar closes another soon opens.”

They may have been run down, but those bars were among the few places where gay and lesbian people could gather. Evelyn Hooker, a UCLA psychologist who studied homosexual men in Los Angeles during the 1950s and 1960s, described the gay bar as the central institution of the homosexual subculture of the time. The bar was a place where “the protective mask of the day may be dropped.”

Lillian Faderman, a co-author of ” Gay LA: A History of Sexual Outlaws, Power Politics and Lipstick Lesbians,” recalled her bar experience in a 2008 speech.

“I came out in the 1950s, at a time when lesbians and gays were made to feel like outlaws by society, and especially by the Los Angeles Police Department,” she said.

“… That gay bar scene in the ‘50s was absolutely crucial for us lesbians and gays—because it was virtually the only place we could be who we were in terms of our sexual identification. It felt like the bar was our little piece of the world… Except that we were often reminded that it wasn’t a safe little piece of the world. Raids were frequent in L.A. gay bars …This was the situation in gay bars throughout the 1950s and much of the 1960s, in Los Angeles and big cities throughout the country.”

That was the case on New Year’s Eve 1967, when a dozen undercover vice officers positioned themselves in the crowded Black Cat.

Highland described the scene in a gay magazine called Tangents: “Midnight came. 1967. ‘Happy New Year!’ A bartender pulled a string and the balloons showered down. The Rhythm Queens yelled a jazz-rock version of “Auld Lang Syne.” Noisemakers squawked. Confetti flew. Kissing is a New Year’s Eve tradition. Did it happen here? If so, it didn’t go on for long,” he wrote.

“Witnesses report: An officer who had been standing next to the Black Cat’s short-order cook suddenly grabbed the cook’s arm and tried to lead him out the back door. It was locked. He turned and steered the cook through the crowd toward the front. Alarmed, a man in woman’s clothes clutched for the front door. The butt-end of a pool cue felled him, one ear split and bleeding …

“[A bartender] went quietly … Maybe not so quietly, but others went too. A dozen of them. For the most part they were the transvestites. The police were trying to build a case. If drag is no longer illegal, juries tend to think it should be. To the public mind it suggests degeneracy. A youth in taffeta, forced to bend across the hood of a patrol car, tore the paper leis from his neck and dropped them into the gutter. They were for happy times and this was not.

“A stout man in a red wig, second-hand movie-star gown and high-heel shoes that were a dazzle of crushed sequins, tried to look inconspicuous. He woke on his stomach on the floor. An officer knelt on his back. Handcuffs clicked. The raid was over. It had taken ten minutes.”

Romanoff wasn’t in the Black Cat that New Year’s Eve. But he was one of the people who, in the wake of the raid, decided it was time to fight. He may be the only person from the protest still living. Romanoff’s husband, David Farah, 55, said that word went out in the community back when the Black Cat was dedicated as a historic site. Besides Romanoff, the only person found was Aristide Laurent, who was too sick to attend the dedication and who died in 2011.

“We would love to know anyone else, too,” Farah said.

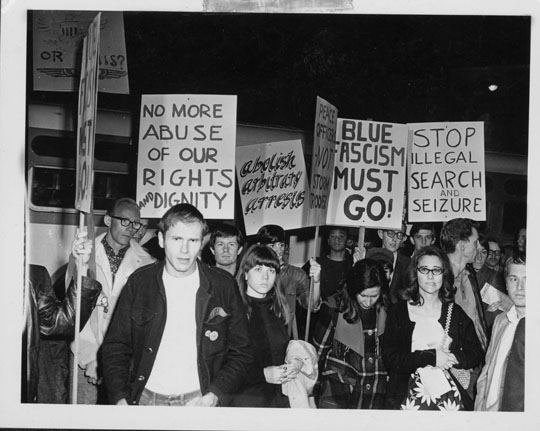

Reports vary on the number of people who attended the protest. Romanoff estimates there were 300 to 600 people there.

“We were very orderly,” Romanoff said. If so much as a leaflet dropped to the ground, it was quickly snatched from the ground to avoid offering any excuse for police to start cuffing protestors. “It was an angry demonstration—but orderly.”

The demonstration was planned by a group called P.R.I.D.E. (Personal Rights in Defense and Education). A Hollywood bar owner agreed to let P.R.I.D.E. organizers meet in the bar during hours when it was closed. A phone tree was set up, with each person calling 10 or 20 others.

People were nervous and feared further violence from the police. That’s why the protest didn’t happen until weeks after the New Year’s raid.

That’s also one reason protests were planned in communities other than the LGBT one. The organizers tried to coordinate simultaneous rallies in black, Latino and other minority communities. The strategy was to spread police forces thin with demonstrations across various parts of the city.

A letter signed by Jim Kepner, curator of the National Gay Archives (now the ONE Archives), mentions the simultaneous rallies.

“The Black Cat attack outraged gays and many others as well,” Kepner wrote. “On February 11, a protest was organized outside the bar by PRIDE, first gay organization largely oriented toward the bar community, and coordinated with similar protests on the Sunset Strip (where Sheriffs were beating hippies nightly for the 6 o’clock news), Watts, Pacoima and Boyle Heights. The overall coordinators howled at the word ‘homosexual’ on our leaflets, so, under pressure, we avoided mentioning our name during the rally, but swore that ‘the love that dared not speak its name’ would never again be silenced. Forty people marched in the picket line, and two hundred of us (and fifty incredibly armed police) participated in the rally in the lot east of the bar. We passed out 3,000 leaflets, chiefly to persons driving by who promised to join us next time.

In a newsletter for the Southern California Council on Religion and the Homophile, Kepner described the scene in court where Baker, Talley and others were on trial.

“The defendants and several supporting witnesses claimed that police, in sports clothes, had not identified themselves as officers, had dragged two of the defendants (bartenders) across the bar onto the floor, and had injured several defendants,” he wrote. “The court steadily maintained that this was not relevant to the case, limiting defense questions to whether the kissing had taken place, how the officers were dressed, and whether kissing constituted willfully lewd and dissolute behavior in a public place, under the statute.”

“[The jury] found all the defendants guilty, except one young bartender, who’d had the foresight to spend the recess in the hallway, in view of most of the jurors, kissing a young lady.”

“There is really nothing new about this story – to homosexuals, or Negroes, or Mexicans, or juveniles, or alcoholics, or others whom some policemen regard as scum. What is new is that homosexuals, who have always been dependably meek, are fighting back …

The fight continues, but in the decades since the Black Cat demonstration in 1967, LGBT people have been winning to a degree that probably would surprise some of those present at that raid. The cat didn’t run away. Indeed, to quote from Harry S. Miller’s song: “The cat came back. We thought he was a goner, but the cat came back. It just couldn’t stay away.”