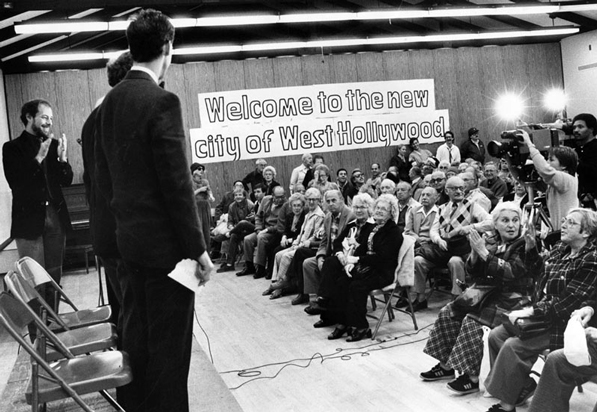

The incorporation of West Hollywood was the work of an unlikely coalition of seniors, gays, lesbians and tenants. The election of three openly gay council members was not so much a tribute to the political muscle of the gay community, but to the progressive attitudes and commitment to diversity of our entire community as all of our newly elected gay officials garnered substantial support from the non-gay citizens of the newly formed city.

The genesis of the incorporation movement was the repeal of the Los Angeles County rent control ordinance. Suddenly tenants were receiving rent increases as high as 30 percent. The repeal of rent control appeared to be a defeat for the tenants’ rights group, the Coalition for Economic Survival, (CES), but the group’s canny director, Larry Gross, immediately turned it into an advantage. Suddenly anxious seniors and gays, people who seldom had reason to interact, were talking at the laundromat, in the check out lines at Safeway and gathered at tables at the French Market, Argos or Theodore’s, debating what to do next.

In face of this devastating event, a soft spoken, bespectacled Ron Stone, a former gay staffer with Senator Alan Cranston, raised the banner of incorporation, envisioning a new city that would be a model of progressive diversity. Ron organized the West Hollywood Incorporation Committee,(WHIC), which became the vehicle for putting the issue of cityhood on the ballot. It proved to be a model of grassroots democracy.

Suddenly the inspirational vision of Stone, coupled with the organizational muscle of Larry Gross and CES, motivated hundreds of residents to ring door bells, create phone banks and register voters. Seniors and gay men were the unlikely shock troops of the cityhood movement as everyone suddenly seemed empowered to create a new city.

Once it became clear that incorporation would be on the ballot, WHIC collapsed, with nearly every member becoming a candidate. Forty candidates vied for five potential council seats, half of them being gay men and lesbians. CES planned to launch its own slate, and Ron Stone resigned as chair of the incorporation committee to run. Bob Craig, the publisher of Frontiers magazine, succeeded to the leadership of what was left of WHIC. Craig electrified West Hollywood’s gay community by announcing that “Gay Camelot” was at hand.

The 40 candidates were an interesting bunch; it was almost as if they were cast as a reality television show. One guy said if elected he would demand that his Westside neighborhood be annexed to Beverly Hills. Mary Beavers, (not a drag name) was a delightfully disconnected senior who promised to build showers for the homeless on the median strip of Santa Monica Boulevard. The city’s Old Guard, the neighborhood leaders who had worked with the Board of Supervisors, included candidates Bud Sigel, Joyce Hundal and Jeanne Dobrin.

Alan Viturbi, an intense 21- year-old whose major claim to fame was founding of UCLA’s Bruin Democrats, was referred to as the “Young Zev” in Democratic circles and was endorsed by the real Zev (Yaroslavsky). Scott Forbes, the owner of Studio One, touted the fact his father was a cantor. Bill Larkin was a former deputy district attorney who owned the property where Revolver was located. Steve Smith was a former aide to state Speaker Willie Brown. Virtually all candidates were united in their support of strong rent control, gay rights and extensive social services, reflecting the progressive values of the community.

But the field was dominated by Valerie Terrigno, the executive director of a small social service organization, Cross Roads, which did outreach to Hollywood’s homeless and street youth. Elected president of Stonewall Democratic Club in January 1984, Terrigno was a dynamically charismatic lesbian who attracted political endorsements from across the Democratic establishment.

The Coalition of Economic Survival did not have a deep bench of qualified candidates. Doug Routh, who worked for the city of Los Angeles, was one of the few candidates with real government experience. CES made a decision to only endorse three members: Routh, Helen Albert, a retired school teacher, and John Heilman, a 25-year-old attorney who had only recently passed the bar. Heilman had volunteered with the local ACLU on gay issues and was one of the few CES members with even minimal gay credentials. CES then added Terrigno and Viturbi to its’ slate to give it wider appeal. Given CES’s proven organizational capabilities and commitment to rent control, its slate had wide credibility.

Not all CES members were happy about this arrangement. Ruth Williams and Norman Chramoff split from CES to run independent campaigns. Joe Thomson ran as an independent. But for the most part, CES’s solidarity remained unshaken.

Sheldon Andelson, a prominent attorney and wealthy property owner in West Hollywood, was not impressed with the cast of candidates. Andelson dominated the West Hollywood Chamber of Commerce and was the most prominent gay person in Los Angeles, appointed by Gov. Jerry Brown to the University of California Board of Regents. He was a power within the Democratic Party. It didn’t hurt that Andelson owned the 8709, a popular gay bathhouse. Money was delivered to his home in the Hollywood Hills each Sunday in over-stuffed garbage bags.

Andelson, Bob Craig and other gay leaders decided that former Gay and Lesbian Center Executive Director Steve Schulte should run in West Hollywood. At the time Schulte was living in Silver Lake gearing up to run for Los Angeles City Council. Presented with an Andelson ultimatum, Schulte relocated to West Hollywood.

In Schulte, the gay community had a proven leader. A Yale graduate, he was strikingly handsome with a casual masculinity, radiating a quite confidence. A former Colt model and a muse of Tom of Finland, Schulte was already an icon within West Hollywood’s gay community. Schulte and Terrigno personified the hopes and awakened aspirations of the gay community, making us realize that in our little 1.9 square miles we could create a new political entity unlike anything the world had ever seen. At a time when the gay community was under attack from the likes of Anita Bryant, the idea of a gay-dominated city was a heady stuff.

I got caught up in it all right after WHIC imploded. The last step was waiting for a report from the Los Angeles County to determine if West Hollywood as a city was economically viable. The report came back positive, even though the county estimated that our municipal revenues would only be about $20 million annually. At that point most residents felt incorporation was a foregone conclusion, and the primary focus was on the City Council races. I walked precincts and made the phone calls like countless other volunteers. I was elected a founding officer in the West Hollywood Democratic Club; it was all very exciting.

The sense that we were somehow making history was palpable. Woody McBreairty, a gay CES Steering committee member, remembers two hundred people showed up at 4 a.m. to distribute door hangers on Election Day. Woody spent the day driving seniors to the polls. Woody was typical of hundred of volunteers who insured the polls were literally flooded.

On Election Day, the CES slate swept four of five seats. Terrigno decisively took the most votes, followed by Viturbi. Albert and Heilman, the two CES members, made the cut, but Steve Schulte edged out CES member Doug Routh for fifth place. With Terrigno, Heilman and Schulte, West Hollywood became the first city in the world to elect a gay majority. Born to the trumpets of international acclaim, West Hollywood was blessed and burdened with huge expectations.

Valerie Terrigno became a national figure, a rock star within the LGBT community. Her first act was to take down the “fagots stay out” sign over the bar at Barney’s Beanery. As mayor, she toured the nation touting West Hollywood’s accomplishment and potential. Terrigno became the focus of the hopes of thousands. Those hopes and expectations were soon to be crushed.

The infighting was almost immediate. Schulte joined Terrigno and Viturbi in an informal coalition. Heilman, the top CES vote getter, seemed to assume that his place at the polls should be reflected in the Council pecking order. It wasn’t. Indeed L.A.’s gay political establishment viewed Heilman as some sort of exotic upstart without any proven credentials to back up his pretensions. The blue dyed hair didn’t help. The gay community identified with Schulte and Terrigno; they didn’t identify with Heilman and they had not voted for him–his support was viewed as being among CES seniors rather than gay men. The comparisons between the iconic looks of Steve Schulte and those of John Heilman got down right ugly and homophobic.

Despite our limited resources, the entire City Council enacted a wide array of social services and passed sweeping human rights legislation that kept West Hollywood in the news. Strong rent control lifted a huge threat to thousands of residents and insured that West Hollywood would remain a funky and diverse community. Closing City Hall for Yom Kippur, after proclaiming it a legal city holiday, caught national attention. Was Harvey Milk’s birthday next?

But reality soon came crashing down. Terrigno was the subject of a heavy-handed federal investigation for pocketing $7,000 from Cross Roads during her tenure. She blamed her lack of bookkeeping skills. The board of directors of Cross Roads, which included its founder, the venerable Morris Kight, provided Terrigno with a paltry salary of $11,500 annually, which seemed to invite this sort of conduct. She was convicted and sentenced to a nominal prison sentence. Many felt the prosecution by the Reagan Administration reeked of homophobia and many felt Terrigno had been betrayed by back-biting community elders. It was certainly a heartbreaking and tragic fall for Valerie.

In 1986 CES succeeded in getting CES member Abbe Land elected to City Council as Terrigno’s replacement. The first gay majority was short lived. John Heilman moved rapidly to consolidate his CES majority and sidelined Alan Viturbi and Steve Schulte. An impotent Alan Viturbi left in 1988, followed by Schulte in 1990. Heilman and Land proved adept at incorporating Terrigno’s cult of personality and gave rise to a tradition of rule by faction. A new myth of our municipal founding omitted Ron Stone. Eventually even references to CES became minimal. After the 1990 election, John Heilman effectively emasculated CES as a political force in West Hollywood.

The fall of Terrigno was an appalling loss. The city seemed disoriented and our dreams discredited. Although West Hollywood remained a beacon, the flamed flickered.

But worse was to come. AIDS hit with full force in mid Eighties, cutting a swath of death though this community. Ron Stone, Bob Craig and Shelly Andelson were suddenly gone.

We not only lost established leaders and pillars of the community but an entire generation of potential leaders and activists. West Hollywood was no longer the news; the plague was the news. Although the city exerted itself valiantly to devote resources to fighting AIDS, running a municipality was now a luxury gay men didn’t have time for. Death stalked our neighborhoods. We needed to save ourselves and save the people we loved.

The euphoria of cityhood proved to be fleeting.

Steve Martin is an attorney and former member of the West Hollywood City Council.

I miss Shelly. He was a good friend when I needed one. RIP

Love it.

Great read. Thanks