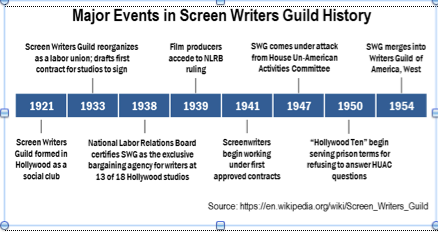

The Screen Writers Guild – the first and most radical of the Hollywood “craft unions” formed in the 1930s – was one of the most disruptive forces ever to hit the motion picture industry. It won a bitter battle with producers to become screenwriters’ official union, only to face congressional investigations into whether Communists had infiltrated Hollywood and infused movies with their propaganda.

This is your front row seat to that period, courtesy of the unincorporated community of West Hollywood, home to some of the Guild’s founders and many of its members who would be “blacklisted” during the so-called “Red Scare.”

Four of the Guild’s 10 founding members lived in this town, along with five of the “Hollywood Ten” who went to prison for refusing to answer questions from the House Un-American Activities (HUAC) about whether they were members of the Communist Party – or whether they belonged to the Guild, for that matter. Nearly five dozen blacklisted actors, directors and screenwriters altogether were West Hollywood residents. (See charts / lists below)

Says It All

Miranda Banks, author of “The Writers: A History of American Screenwriters and Their Guild,” http://www.amazon.com/The-Writers-History-American-Screenwriters/dp/0813571383 asked producer Norman Lear (“All in the Family”), “Why do you think writers have been at the forefront of labor disputes in Hollywood?” He replied, “Maybe because they’re paid to think.”

Look for the Union Label

First, let’s get caught up on a few key pieces of background, and one that’s just bizarre.

• Who remembers screenwriters’ original goal when they formed a protective union? Answer: They wanted to keep the status quo on salaries and working conditions. That doesn’t sound radical, but the studios had forced pay cuts of 50 percent on screenwriters and other creative workers. According to Banks, the Guild was formed to restore salaries to previous levels.

• Many screenwriters’ careers were ruined when they wound up on a “blacklist” generated by the HUAC. But did you know that the first Hollywood blacklist actually came from the studio heads themselves in 1936 – at least a decade before the HUAC’s so-called investigation? When word of the informal blacklist leaked, the Guild went underground, as no screenwriter could afford to be caught carrying its membership card.

• Dalton Trumbo is widely known as an Academy Award-winning screenwriter and arguably the most talented of his time. But he also was just as well-known as a left-wing political activist whose sympathies coincided with those of the American Communist Party, which hewed to the line set by Moscow.

That’s why it’s hard to believe that, as a high school student in Grand Junction, Colo., Trumbo once asked his father for five dollars so he could join the Ku Klux Klan, a mass organization formed after World War I. He didn’t get the five dollars, according to the Internet Movie Database.

A quick note about the temper of the times: New Deal reforms pushed through Congress by Franklin D. Roosevelt in his first year as president favored union organizing. The studios, in contrast, were beginning to feel the effects of the Great Depression full force, just as they were completing an expensive transition to new technologies like sound-on-film.

The “WEHO Founding Four”

You couldn’t ask for a more talented or accomplished group of screenwriters than the 10 screenwriters who founded the Guild. These four were West Hollywood residents.

• John Bright was best known for co-writing the script for “The Public Enemy” (1931), which earned him an Academy Award nomination for Best Story. The movie was one of the first of the gangster genre to examine the sociological roots of crime in a serious way – a subject he knew first-hand from his days as a soda jerk at a Chicago drugstore.

Many of the city’s most notorious gangsters hung out at the drugstore where Bright worked. It was there Bright met Al Capone. Bright was present at a banquet at Chicago’s Commonwealth Hotel when Capone ordered the murder of two attending Mafiosi who had displeased him. The men were immediately beaten to death with baseball bats in front of Bright, an incident later dramatized in Brian DePalma’s “The Untouchables” (1987).

In the early 1950s, when the HUAC investigated what it termed Communist subversion of motion picture production, Bright moved to Mexico to avoid congressional scrutiny and was subsequently blacklisted.

• Frances Marion, one of Hollywood’s most renowned and respected screenwriters of the 20th century, served as the Guild’s first vice president. She won Oscars for her writing on “The Big House” (1930) and “The Champ” (1931).

Marion wrote the stories and scenarios for more than 300 films. According to a biography by JoAnne Ruvoli. She excelled at writing scripts that accentuated the strengths of specific actors and is often credited with defining the careers of Marie Dressler, Greta Garbo, Marion Davies and Mary Pickford as well as her husband, cowboy star actor Fred Thomson.

• Dorothy Parker, a founding member of the celebrated Algonquin Hotel Round Table group of New York writers, critics and actors, was forever the sharpest wit in the room. She also was a master of short fiction and very highly regarded for her work on “Little Foxes” (1941) and “Saboteur” (1942). Parker was an Academy Award nominee in 1937 for “A Star Is Born.”

All of that counted for nothing during the “Red Scare” concocted by the House Un-American Activities Committee

(HUAC) in 1947, though. She was blacklisted for her involvement with the Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA) in the 1930s. Still, Parker is fondly remembered for lines like:

Q: Give me a sentence using the word horticulture.

A: You can lead a horticulture, but you can’t make her think.

And then there’s this ditty:

Once in her long-running feud with Clare Boothe Luce, Mrs. Luce held the door open for Mrs. Parker to walk through and said, “Age before beauty.” Mrs. Parker walked through and said, “Pearls before swine.”

• Donald Ogden Stewart won an Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay for “The Philadelphia Story” (1940). Other notable movies on which he worked include “Holiday” (1938), “Life with Father” (1947) and “Love Affair” (1939) – all sophisticated, witty, light, romantic comedies and melodramas that became his trademark during Hollywood’s Golden Era.

His co-founding of a Communist front organization in 1936 called the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League (HANL) drew much different kinds of attention, though. The HANL was one of the first groups targeted by the HUAC. Stewart acknowledged being a member of the Communist Party-USA during an HANL meeting and was blacklisted in 1950. The following year, he and his wife emigrated to England, where they lived until they died in 1980. Stewart’s HANL co-founder, by the way, was fellow screenwriter Dorothy Parker.

What Did the Screen Writers Guild Accomplish?

The Guild was an unlikely winner in its unionization fight with producers, who outmaneuvered writers time and again. Plus, dissension permeated the Guild’s ranks, nor was the fledgling union able to unite similar organizations under its wing so all writers spoke with a single voice.

Given up for dead, the Guild gained new life when the National Labor Relations Board certified it as the exclusive collective bargaining agency for writers at 13 of 18 Hollywood studios in 1938. A dissertation by Christopher Dudley Wheaton http://digitallibrary.usc.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/p15799coll24/id/349140/rec/2 says the Guild’s success (1) established it as the first large “craft guild” or union for creative workers; (2) created a minimum basic agreement for creative talent contracts; and (3) injected political radicalism much further to the left than previously seen in Hollywood.

Authors Larry Ceplair and Steven Englund (“The Inquisition of Hollywood”) say the Guild served “as the prototype for other talent guilds; its members were the backbone of every other political and social organization in the film community and three times within the first decade and a half of its existence it seriously shook the studio front offices.”

A Slight Case of Communism

When the political pendulum swung far right in the late 1940s, Congressional conservatives began a full-scale assault on those who had promoted political change and social reform since the start of the Great Depression. Union organizing from 1929 to 1939 was considered a radical political activity that landed many screenwriters on the official Hollywood Blacklist. The Guild specifically was portrayed as a haven for communists according to “SAG and the Motion Picture Blacklist” by Larry Ceplair .

The committee mainly was concerned with investigating centers of communications, including universities, the publishing community and the motion picture industry.

“It was no coincidence that the vast majority of those blacklisted had been in the forefront of organizing unions,” states an analysis of the period by the Screen Actors Guild. http://www.cobbles.com/simpp_archive/linkbackups/huac_blacklist.htm The “Hollywood Ten” emerged, consisting of those who served up to one year in prison for refusing to state whether they were Communists.

“WeHo Five” among the “Hollywood Ten”

Of more than 300 people on official and unofficial blacklists, at least 58 lived in West Hollywood at some point during the “Red scare” investigations, according to a WEHOville analysis. Of those on the Hollywood Ten list, five were West Hollywood residents.

• Lester Cole was best known for “Blood on the Sun” (1945), “Objective: Burma” (1945) and “Among the Living” (1941). After he got out of prison, Cole began collaborating on screenplays using an assumed name. One of his scripts, written under the pseudonym “Gerald L.C. Copley,” was made into the popular movie “Born Free” (1966).

• Albert Maltz labored as a screenwriter for Warner Bros., which had made its reputation in the 1930s for socially aware dramas. He worked on the classic “Casablanca” (1942) and wrote the Oscar-winning documentary “The House I Live In” (1945), a plea for racial tolerance, and was nominated for an Oscar for writing “Pride of the Marines” (1945). Maltz joined the Communist Party in 1935 and was unrepentant about his progressive politics until his death in 1985.

• Samuel Ornitz, screenwriter best known for “Little Orphan Annie” (1938), “A Doctor’s Diary” (1937), “Three Faces West” (1940) and “Army Girl” (1938). As a screenwriter, Ornitz never lived up to his early promise as a writer. He did have a major impact on Hollywood, however, as an early organizer and board member of the Screen Writers Guild. The SWG was the first and most radical of the Guilds, and despised by the powers that be in Hollywood for its success in organizing labor.

• Adrian Scott, a screenwriter, made his biggest impact on Hollywood as a producer, helping to create the genre later

known as “film noir.” In the mid-1940s at R.K.O., working with director Edward Dmytryk and screenwriter John Paxton, Scott produced “Murder, My Sweet” (1944), a detective thriller based on Raymond Chandler’s’ “Farewell My Lovely” with Dick Powell as Philip Marlowe.

But it was for the gritty noir masterpiece “Crossfire” (1947), the first Hollywood film to deal with anti-semitism, that the group is best known. “Crossfire” was nominated for five Academy Awards, including Best Actor in a Supporting Role (Robert Ryan), Best Actress in a Supporting Role (Gloria Grahame), Best Director (Dmytryk), Best Writing-Screenplay (Paxton) and Best Picture (Scott).

For Scott, it would be the last motion picture he’d ever produce. Both he and Dmytryk were called before the HUAC in 1947, where they refused to name names. While blacklisted, Scott survived by writing for television under an assumed name, including such all-American fare as “Lassie.”

• Dalton Trumbo was an Oscar-winning screenwriter and arguably the most talented and most famous of the blacklisted film professionals known as the “Hollywood Ten.”

Trumbo won his first Oscar nod for RKO’s “Kitty Foyle” (1940). By the time of America’s entry into World War II, Trumbo was one of the most respected, highest paid screenwriters in Hollywood. He had also established a name for himself as a left-wing political activist whose sympathies coincided with those of the American Communist Party (CPUSA), which hewed to the line set by Moscow.

After his blacklisting and the failure of the Hollywood 10’s appeals, the Trumbo family exiled themselves to Mexico. While there, chain-smoking in a bathtub where he always wrote, usually with a parrot given to him by ‘Kirk Douglas’ perched on his shoulder, Trumbo wrote approximately 30 scripts under pseudonyms and using fronts who relayed the money to him.

Blacklisting effectively ended in 1960 when it lost credibility. Trumbo was publicly given credit for two blockbuster films: Otto Preminger made public that Trumbo wrote the screenplay for the smash hit “Exodus” (1960), and Kirk Douglas publicly announced that Trumbo was the screenwriter of “Spartacus” (1960). Further, President John F. Kennedy crossed American Legion picket lines to see the film.

On Dec. 19, 2011, the Writers Guild of America (WGA) announced that Trumbo was given full credit for his work on the screenplay of the 1953 romantic comedy “Roman Holiday,” almost 60 years after the fact. The WGA is the successor union to the Screen Writers Guild, formed through a merger in 1954.

“What’s All This Business about Being a Writer?”

This closing anecdote – also from the Miranda Banks book published this year about screenwriters’ history – shows how writers’ lack of recognition played out daily.

“Irving Thalberg, the much-celebrated head of production at MGM in the 1920s and 1930s, interrogated the writer of ‘Street of Chance’ and script doctor Leonore Coffee at a story meeting. “What’s all the business about being a writer? It’s just putting one word after another,” Thalberg said. To which Coffee responded, “‘Pardon me, Mr. Thalberg. It’s putting one right word after another.’”

Bob Bishop is a retired public relations manager and journalist who writes about local history for WEHOville. Contact him at [email protected].

Page 2 below: West Hollywood actors and director on blacklists, with their addresses and films

Page 3 below: West Hollywood screenwriters on blacklists, with their addresses and scripts.

well, someone has to be the adult here…

perhaps a less rosy view of these victims is warranted.

check out this more serious piece of journalistic analysis from laobserved.com

offers a bit of perspective and broader context of the times.

http://www.laobserved.com/intell/2015/11/what_trumbo_doesnt_tell_us.php

Yes, great resource!!!!

https://staging.wehoville.com/2013/12/10/witty-wise-dorothy-parker-life-now-weho/

Dorothy Parker lived at 8983 Norma Place, where husband Alan Campbell killed himself. Shortly after, a neighbor, seeing her, asked how she could help. Her reply – “Get me a new husband.” The shocked neighbor recoiled; Parker then said, “If not, then run down to the corner and get me a ham and cheese on rye. And tell them to hold the mayo.

Sounds like she fit right into our city.

Wonderful piece, Bob. A really shameful time in this country when every problem was blamed on secret Commies. It’s always easier to have a scapegoat (gays, Communists, feminists, immigrants), than looking within to search for solutions.