It’s 1984, the band Devo has put out three albums since its breakout 1980 Freedom of Choice and its hit song “Whip It” is still everywhere.

Front man Mark Mothersbaugh, with more money in his pocket than he has ever seen in his life, decides to stop staying on Iggy Pop’s couch at the beach and buys a house in the hills above Sunset Plaza.

David Bowie and Brian Eno had brought Devo out to L.A. to help them secure their first big record deal. Now Devo is rehearsing and recording in Marina del Rey, and Mothersbaugh makes the bumpy commute from West Hollywood in a rattling, sputtering old Mercedes.

Each day he drives by a circular building on Sunset Boulevard, and each time thinks, “if I worked here I would be recording already!” Ringed by curve-topped windows, it looks like a miniature version of the L.A. Forum crossed with a carnival Gravitron. It’s round, it’s weird, and it’s for sale.

***

The building was then occupied by a Russian holistic medical clinic. The clinic had put rose-tinted glass in the windows. The hideous brown and maroon striped decor featured a floor tiled with cheap cake frosting textured squares. The outside had been painted a dull putty, the color of dead skin.

Others had showed interest in the building, looking to turn its unique shape into a restaurant, club or pool hall, but each plan was abandoned due to a lack of parking. Its price constantly dropped, and when it was within his range in 1995, Mothersbaugh bought it to house Mutato Muzika, his new multimedia production company. (The name Mutato is a combination of the words Mutant and Potato.)

The idea of mutation is important to Mothersbaugh. It describes how imperfections change things from one form into the next and sums up his approach to making art and music. Mothersbaugh is an artist of diverse talents and Devo incorporated a variety of artistic media. The band itself designed all the graphics, costumes, videos, performance and music–a total package. The new space at Mutato would allow him to explore all these interests under one round roof.

The interior was refinished the interior with a few small alterations so it would work for music production. Since moving in, the building has hosted names like David Bowie, Brian Eno, Iggy Pop, The B52s, Debbie Reynolds, Lou Rawls and numerous others. The outside was painted green, a shade of Chernobyl Cucumber chosen to neutralize the rose tint of the windows.

At home there for the past twenty years, Mothersbaugh successfully mutated Devo into Mutato and medical clinic into multimedia art space, with only cosmetic changes. But these are only two of a huge number of transformations that happened in this building.

Originally built for Dr. Robert Alan Franklyn and designed by Brazilian architect Oscar Niemeyer, it housed one of the top cosmetic surgery clinics in the country and was one of the birthplaces of breast augmentation.

It’s 1967, and Dr. Robert Alan Franklyn, strolling from his office to the central sky-lit operating room, stops at the door to put on his sunglasses. The room is bright and the sky above cloudless, only the tops of palm trees peek past the oculus in the ceiling. Sunbeams shine on sterilized surgical instruments.

Franklyn looks at the blonde anesthetized on the sun-faded operating table. Surgiform breast implants that seem closer kin to florist arrangement foam lie on a metal tray. Frankyn is ready to make a star.

In the waiting room, a woman whose gleaming Harley Davidson leans in the driveway, walks in and, in an apparent reference to her breasts, asks, “Hi Mac, you fix flats?”

Cosmetic breast augmentation was a novel procedure in the 1960s, and Dr. Franklyn, as one of the few doctors to focus solely on cosmetic procedures, was the go-to entertainment industry surgeon.

In his book, Beauty Surgeon, he describes the first patient who came to him seeking breast enhancement. She was a beautiful blonde striptease dancer with a flat chest, known as “the shy one” because she never removed her padded brassiere.

She was looking for help, and Franklyn felt that the kind of psychological distress her lack of bosom caused her was rampant in the United States. There had been a cultural shift in body type preference, thanks to images of Marilyn Monroe and Jane Russell that had women everywhere feeling inadequate.

“I have a great sympathy for most of the people who come to me. I may not be changing the course of the world, but my work is of inestimable value to the individuals I treat. Some of them are referred to me by psychiatrists, and sometimes they become totally different—and infinitely happier—people after an operation,” Franklyn said in his Sports Illustrated interview.

While today we might address the damage of such a perception with therapy or a larger social campaign, Franklyn treated the symptoms of those individual women who could afford it breast by breast. He even touted the reversibility of the procedure should tastes change.

No procedure then existed that could enlarge the breasts, so he invented one. Using foamed plastic he had pilfered from the seat cushions of a WWII German fighter plane he had seen in an exhibition, he developed an implant he dubbed “Surgifoam.”

After implantation of foam from the German plane, the striptease queen became known as “Chesty” and, if Franklyn is to be believed, the confidence of added bounce in her blouse helped her to leave dancing, find a husband and live happily ever after.

Franklyn had (and continues to have) a dubious reputation in the medical community. This comes (surprisingly) less from his implantation of German aviation foam in a woman’s chest than from his habit of speaking directly to the public about his work. Franklyn put cosmetic surgery into the public’s imagination.

He was more likely to be seen pushing his procedures in the pages of the Weekly World News alongside UFO abduction stories than in a professional medical journal. He was deemed reckless and unscientific.

Despite this scorn, Franklyn was wildly successful, so much so that he could afford to construct a building for his practice on Sunset Boulevard. Not one to miss an opportunity to make an impression, the media savvy doctor proposed something big, hiring Brazilian architect Oscar Niemeyer.

***

His morning cigarillo in hand, Oscar sneaks a peek at the waitress’ backside as she walks away with the coffee pot. “French women are too skinny” he thinks to himself, his mind straying to visions of baroque proportions.

He is designing a 13-story office tower and beauty clinic for a Los Angeles surgeon and must work on the road. Looking out of the cafe window, he sees a bank of clouds roll across the sky. Where most might see a bird, a puppy or a zeppelin, Oscar has Rubenesque visions. Legs, hips, breasts and nipples explode every edge, aporous vaginas flow open and closed in the wind.

Looking back down at his sketchpad, he quickly roughs out a series of shapes, structures, and forms inspired by these feminine-inspired hallucinations. A profile and floor plan emerge. He adjusts the form, the shape of the columns, adds windows, a figure for scale.

He sighs, no trip to California this year. The sketches will need to be developed, copied and mailed to L.A. from Paris. The letter rejecting his application for a U.S. visa is still in his briefcase.

***

The combination of famous architect and infamous client seems a strange fit at first and has generally been treated as myth. Why would Niemeyer, who had designed giant sculptural buildings all over Brazil, take on such a small commission in West Hollywood?

Niemeyer had been exiled and banned from working in Brazil because of his Communist activism in 1964, when a coup brought a new military government to power. He was likewise denied an entry visa to the U.S. the same year. It was during this period of exile, working from Paris, that Niemeyer designed his two California projects. Working with local architects by mail, he completed a house for Anne and Joseph Strick in Santa Monica and the Beauty Pavillion for Dr. Franklyn in West Hollywood.

While the Stricks hired Niemeyer as a protest to U.S. policies, Dr. Franklyn was more interested in Niemeyer for the design inspiration he found in female beauty and had contacted him before his exile in 1963. Dr. Franklyn, in partnership with his mother Theresa, hired Niemeyer to design a 13-story office tower on their Sunset Boulevard site in West Hollywood, a significant commission for the soon-to-be-homeless architect.

“I started following Niemeyer’s work in 1943 when he was nothing,” Franklyn told Sports Illustrated.

Zoning applications describe the tower as round, with a lobby, landscaped plaza, ten floors of office space, two floors for Dr. Franklyn’s cosmetic surgery practice and a penthouse on top.

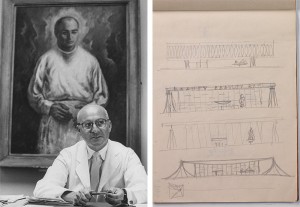

For reasons that remain unknown, the tower proposal was withdrawn by Franklyn in 1965. The project mutated into the modest two-story circular clinic that Niemeyer stayed on to design and was constructed in 1967. Drawings of the original tower remain lost, but within the archives of the Oscar Niemeyer Foundation in Rio de Janeiro, Niemeyer’s sketches for the Beauty Pavillion, or “Centro de Beleza,” show numerous versions of the two-story clinic.

***

Like Mark Mothersbaugh’s combination of the words Mutant and Potato to create Mutato, the combination of Dr. Franklyn and Oscar Niemeyer is a match that ended up producing a unique building.

Niemeyer’s oft-repeated personal dictum was that “form follows beauty,” and Dr. Franklyn clearly could not have agreed more. When it came to the topics of beauty and women, they were soul mates.

Niemeyer always had women and sex on his mind. Crude comments were a staple of his office, as were photographs of breasts and butts, everywhere he looked. Dr. Franklyn was obsessed with symmetry, circles and the banishment of physical imperfections.

The Beauty Pavillion reflects the inspirations of both men. Round and perfectly symmetrical, like a newly sculpted Dr. Franklyn breast, complete with nipple dome skylights and a facade ringed with vaginal window openings, the driveways gently curve under the backside. It is a mutant woman object.

Inspired by women but still a Modernist, Niemeyer was not out to build the womanly version of “Randy’s Doughnuts”—a building advertising what it housed. His vision was more universal, focused on beauty for beauty’s sake.

With the Beauty Pavillion, Niemeyer’s vision was mutated, outmaneuvered by a master of American media culture. His forms followed beauty but became metaphor. Franklyn’s involvement twisted Niemeyer’s vision, the clinic and what happened inside was a billboard for Franklyn’s work. The building ended up as much a surgically perfected woman as a Googie restaurant is a classic car.

This is not necessarily a distasteful conceit on Franklyn’s part, as it puts Niemeyer’s work in a unique light. Its mutant history also makes it a perfect home for Mothersbaugh, an artist who sees the value of mutants as creatures of progress, the way that things change from one into the next, combining two slightly different things to create an entirely new third being.

EDITOR’S NOTE: This is the cover story in the Spring issue of West Hollywood Magazine. To find a copy, look here: WestHollywoodMag.net.

It would be interesting to find out if Dr. Franklyn’s daughters have the blue prints of the original 10-story building. I had the opportunity to meet Dr. and Mrs. Franklyn as I have been friends with their daughters since elementary school. In 1965 Dr. Franklyn’s daughters were born so I’m wondering if that had something to do with the change of plans. Next time I see them I’m going to ask them all about the beauty pavilion.

While it’s interesting to learn of 8760 Sunset’s colorful history, design pedigree and ownership, it doesn’t necessarily negate the fact that it’s ugly, out of scale and a prime example of how many mid-century modernist buildings are sculpturally interesting but have no humanist connection to their environment or a pedestrian / streetscape connection to the public realm. Every time I walk past it I am reminded of the “void” it creates in the streetscape. I am not sure architectural misses, even those conceived by famous architects with colorful pedigrees, are worth “preserving” for posterity. If one wishes to experience mis-guided… Read more »

I love the cosmetic surgery history of this building. I also hope that the City designates this commercial building as a historic resource (if it hasn’t already) to insure preservation of the structure. Niemeyer built some amazing mid-century modernist buildings in his native Brazil and he is internationally-recognized as one of the great architects of the 20th Century.