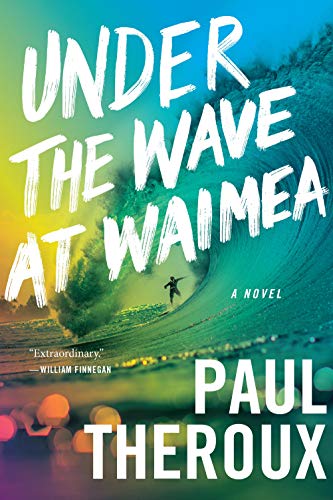

Travel writer and novelist Paul Theroux will discuss his bestselling newly released 52nd novel, Under the Wave at Waimea, at 6 p.m. Wednesday at Book Soup at 8818 Sunset Blvd, West Hollywood.

The novel, which follows Houghton Mifflin Harcourt` released Tuesday follows “a big-wave surfer as he confronts aging, privilege, mortality and whose lives we

choose to remember.”

Prospective participants may register at https://www.crowdcast.io/e/paul-theroux-discusses.

Theroux is also hosting a social media giveaway contest to celebrate his new book, with a grand prize of a three-night stay with breakfast for two in a Water Villa with pool at Four Seasons Resort Maldives at Kuda Huraa including return speedboat transfer for two.

Luxury surf company Tropicsurf will also sponsor three days of complimentary private guiding and coaching to the winner, with all day access to any North Malé surf break via a private speedboat with a personal Tropicsurf guide, and all necessary equipment for a truly luxury surfing experience.

More prizes from Four Seasons Resorts Bali, Silversea Cruises, Cathay Pacific, Turtle Bay Resort, Herringbone, and signed bookplates by Paul Theroux available!

Here are the steps to enter:

- Order your copy of Under the Wave at Waimea on Amazon, Indiebound or your local bookstore

- Snap a photo of yourself with the book or of the book in your favorite spot to read, post to Instagram and tag @Paul.Theroux by April 30.

- Check back to The Surf Wall page to see your photo featured.

“Under the Wave of Waimea,” by Paul Theroux (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 421 pages, $28)

Here’s an excerpt from Under the Wave at Waimea:

The Island of No Bad Days

The one wild story that everyone believed about Joe Sharkey was not true, but this was often the case with big-wave riders. It was told he had eaten magic mushrooms on a day declared Condition Black and dropped left down a forty-five-foot wave one midnight under the white light of a full moon at Waimea Bay, the wave freaked with clawed rags of blue foam. He smashed his board on the inside break called Pinballs and, and unable to make it to shore against the riptide, he swam five miles up the coast, where he was found in the morning, hallucinating on the sand. More proof that he was a hero; that he surfed like an otter on acid.

His being found on the beach at dawn near Banzai Pipeline was a fact, and he’d taken LSD, not mushrooms. But so much of the rest of his life had been outrageous, and sometimes heroic, glowing with sensuous happiness, that his fellow surfers never questioned whether the wave had been a monster, or if he’d been on it, or broken his board, or swum alone to Pipeline, nor did they accuse him in pidgin of bulai — lying. Sharkey had shown himself the equal of the best of them. When he’d first been asked about the Waimea story, he’d been young — eager to make an impression, and prone to embellish. In time he learned that exaggeration was always a side effect of fame and fiction a feature of every surfer’s reputation, the yearning to be a dog off its leash.

The appeal of surfing to Sharkey was that it was improvisational, a question of balance; of staying on your board on a radical feathering wave, a dance on water, at its best a display of originality, perhaps not a sport at all but a personal style, a way of living your life, a game without rules, incomparable. And some of the greatest rides, on the biggest waves, were never seen by anyone except the surfer. The surfer rode the wave, the wave blobbed softly, and it was over, the epitome of performance art. The surfer paddled to shore, the wave was gone, there was no trace of the ride — something like a fabulous death.

His lover, Olive Randall, knew the truth, because (being new to his life, and English, and a nurse) she’d asked in her forthright way, “So what about it, then, you grinning numpty?”

And she looked for more. Sometimes—the way the earliest humans studied a stranger—she examined his body to read his history and know him better. He slept naked, and often in their first month together she woke beside him and searched for meaning in the ink on his skin. Much of the imagery was obvious, some of it obscure, a great deal was a record of risk; his disfigurements were those of a warrior, battle scars and scabbed wounds and the sutures from wipeouts and jellyfish stings and face-plants.

In the early hours of muted sallow daylight his tattoos were mottled like bruises, but after sunup they were sharpened, as he lay, facing away from her, his back exposed, a great blue wave covering it like a dragon’s mouth, fanglike foam on its jagged crest tipping past the top of his spine, the well-known print of the Japanese wave at Kanagawa that most people recognized, except that in this depiction Sharkey was surfing the great curved face of it. In his tattoo he was crouched on his long board, one arm extended, as he had surfed a forty-five-footer at Waimea or the great wave at Cortes Bank. But Cortes was so far offshore — a submerged island more than a hundred miles in the ocean west of San Diego — only the boatman had seen him, and few people knew that it was one of his triumphs.

Tribal slashes of black, licks and ribbons, covered his upper arms and deltoids, and the syllable Om in complex Tibetan brushstrokes on each declivity of his shoulders. His arms—“full sleeves”—were enclosed by bands of sharks’ teeth, stylized, triangular. A snake circled his left wrist like a bracelet, an ouroboros, its tail in its mouth. On his right arm more sharks’ teeth, a frigate bird on the back of his hand — his power animal, he called it — flattened, his wings outspread, also serving as the image of a compass. Some were faded, some were fresh, all had meaning.

Hawaiian dots, many of them like pinpricks, a constellation of them on his fingers, and balancing that pattern the Southern Cross on his right foot, below an anklet of dolphins. Tattoos hammered into his skin, rat-tatted with blunt inky spikes in Tahiti and Samoa and poked into him with a chattering needle in Santa Cruz and Recife and Cape Town; Devanagari script from India, a lozenge that looked Egyptian, single words, like the name on the meat of his thumb — an old girlfriend? Olive had finally asked him, but no. “My mother,” and he seemed lovable saying that.

“Your mum,” she said. She cocked her head at him and kissed him. “Your muvva.”

UNDER THE WAVE AT WAIMEA

By Paul Theroux

409 pp. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. $28.

Copyright 2021 © by Paul Theroux

Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.