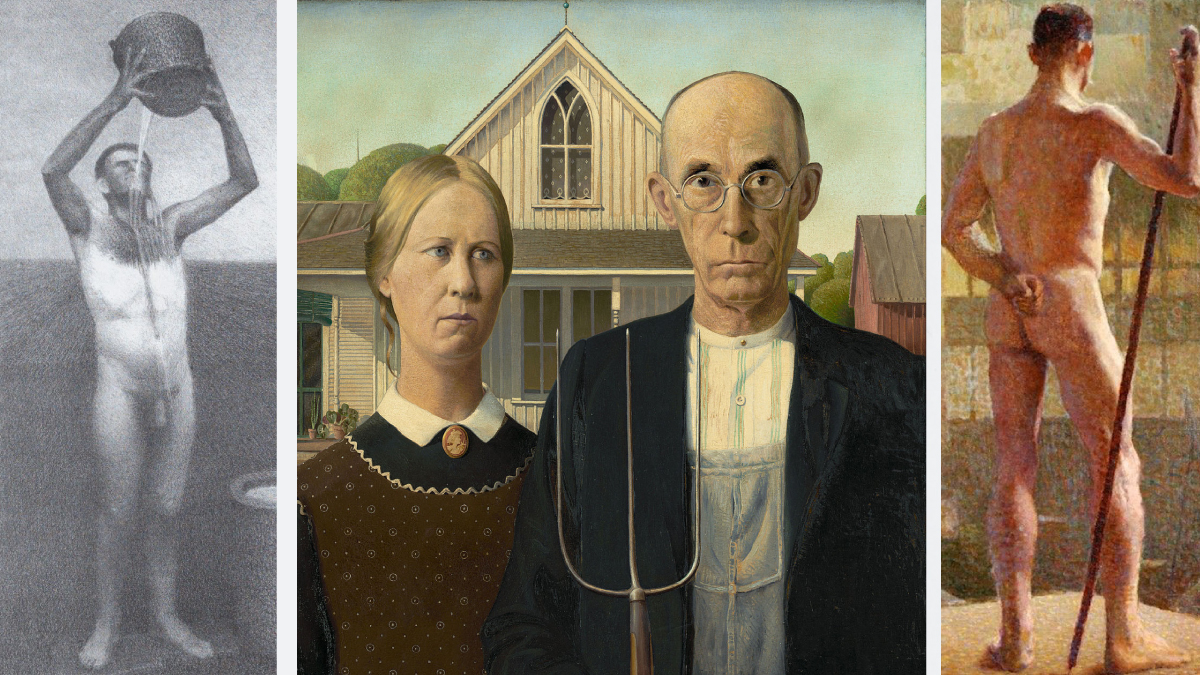

In this article for the GAY & LESBIAN REVIEW I discuss the extraordinary triangle between Grant Wood, the queer creator of the iconic painting American Gothic, his numerous male assistants, and Wood’s oppressive sister Nan, who posed for the painting and denied her brother’s homosexuality until her death. Their tangled relationships transformed American art. For more information and related articles, please check https://glreview.org/

When you talk about the painter of American Gothic, Grant Wood (1891–1942) it’s easy to buy into the irresistible image he created of a homespun artist of rural America. But, just as in his archetypal painting, there’s much more than meets the eye.

Having researched Wood for a decade, I’ve seen how publications and exhibitions tend to stick to the official version of his life, keeping him in the closet. This fable was finally blown to smithereens by a recent retrospective at the Whitney Museum, which dared to declare that “Wood’s homosexuality is the code that unlocks the truth to his art.”

Here is the extraordinary story of the unconventional triangle between the iconic artist, his numerous male assistants, and Wood’s oppressive sister Nan (1899–1990), who posed for American Gothic and denied his sexuality until her death. Their tangled relationships ended up defining and transforming American art.

The seeds of Wood’s queer (in more ways than one) life were planted in his childhood. His father was a stern and unemotional Quaker who believed all artists to be sissies. His mother Hattie encouraged Wood’s creative abilities behind her husband’s back.

Mortified by the fact that he looked nothing like his two brothers, Wood was thrilled when his sister Nan (for Nancy) was born and she looked just like him. This marked the beginning of Wood’s lifelong, unbreakable bond with his mother and his sister. While his brothers took after their father, Grant, who was pudgy and clumsy, rarely worked on their farm. Born right when the term “homosexuality” was first used in the U.S., Wood used his quirky sense of humor to navigate his challenging life. In his unfinished autobiography, filled with none-too-subtle homoerotic stories, he recalls a preacher pointing at him during a chilling sermon about Sodom and Gomorrah “just when he was daydreaming about joint snakes.”

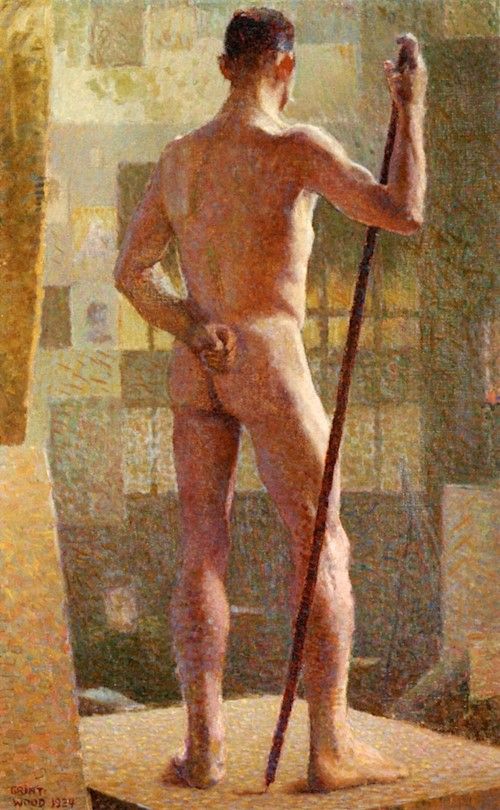

In 1916, after his father’s passing, Wood, Hattie, and Nan moved into a one-room shack in Cedar Rapids, the Iowa town that would become the center of his personal and artistic life. Wood became the surrogate head of the family with the scant income he received from jewelry designs and his work in a metalwork shop. In these days, the United States was considered a cultural backwater, but Wood was determined to become a reputable artist. He knew that studying in Europe was essential, so he proceeded to make four trips abroad throughout the 1920s, starting with France to study Impressionism. Chubby, shy, and with a bit of a Peter Pan complex, Wood was unable to use his only social tool, his wit, because he didn’t speak French. In Paris, he experienced gay culture for the first time in the company of fellow artist Marcel Bordet, whom he nearly brought home to mother. In those joyful days, he painted a large male nude, The Spotted Man, one of only two of his paintings that he kept until his death.

Back in Iowa, he told a friend “I guess I’m not interested in women,” and his life revolved around his devoted relationship to his mother and sister. Wood’s first art patron, David Turner, offered him a 975-square-foot hayloft behind his funeral home as a rent-free studio. Wood gladly accepted and, a true Renaissance man, designed furniture that could be stacked and concealed, creating an open studio that anticipated the design of today’s SoHo lofts

After some prodding, his mother moved in and took care of all his domestic needs. His sister spent long periods with them, sharing their bedroom space even after she got married, because of her husband’s bad health from tuberculosis. In spite of this tight living arrangements, with the mingled smell of oil paint and fried bacon, the decade they spent there would become the most productive and successful of his career. When he arrived in 1924, he was just a local artist. When he left, he was a star of the art world.

Wood’s homosexuality was an open secret in Cedar Rapids, where a tiny gay and lesbian subculture was tolerated, so long as it remained invisible. Coming out would have threatened his reputation, freedom, and income. He winkingly carved in a school bench: “The way of the transgressor is hard.” As the owner of his favorite bar put it: “Grant Wood is gay only when he is drunk.” His armor started cracking when the Des Moines Tribune mentioned his bachelorhood, his feminine tastes, and his appearance. As a protective mechanism, Wood downplayed his worldliness and fabricated a new persona, branding himself the farmer-artist of America, wholesome, and of course heterosexual. He shaved the bohemian beard he’d grown in France and adopted denim overalls as his uniform, flaunting them in photographs and interviews, once proclaiming that “All the really good ideas I’ve ever had, came to me while I was milking a cow,” even though he hadn’t lived on a farm since childhood.

In 1927, Arnold Pyle (1909–1973), one of Wood’s former students, became his assistant. Pyle was eighteen and Wood, 36. Good-looking, tall, athletic, with thick black hair, the heterosexual Pyle epitomized the type of man Wood continued to fall for, over and over, throughout his life. In all of his intimate but unrequited relationships with his young protégés, Wood would disguise his desire under the façade of paternal affection toward an admiring pupil. This alibi allowed his status quo to remain unchallenged, keeping scandal at bay.

When Wood got the commission for a stained-glass window in the Veterans Memorial Building, Pyle modeled for the image of a bare-chested cannoneer, next to whom stands a soldier with a strong resemblance to Wood. In 1928, Wood traveled to Munich to supervise the glass manufacturing. The gay community he experienced in Paris was open but marginalized. In Weimar Germany, however, gay men were at the center of society, completely accepted and assimilated. With his plump physique and reddish hair, Wood blended seamlessly into this society. This is a shock to his system, forcing a dilemma: stay in Europe and abandon his mother, sister, and that whole world, or give up his newfound sexual freedom and return to Iowa. In German museums, he was dazzled by medieval artists such as Dürer and Memling, who painted their simple surroundings and created detailed and realistic portraits in which the sitters posed as archetypes, holding symbolic props.

This revelation transformed him as an artist. When he returned to Iowa, he saw the landscapes and people he had taken for granted in a whole new way. Realizing that his early Impressionistic work made him appear less than manly, he pretended that he never took it seriously, calling it “wrist work.” Instead, he applied the newly discovered ultra-detailed European technique to his American roots. This style, eventually labeled Regionalism, glorified rural America and pushed aside the artistic influences of Europe and the East Coast.

Wood embraced it when it became widely popular with conservative critics and patrons, and he never left the U.S. again.

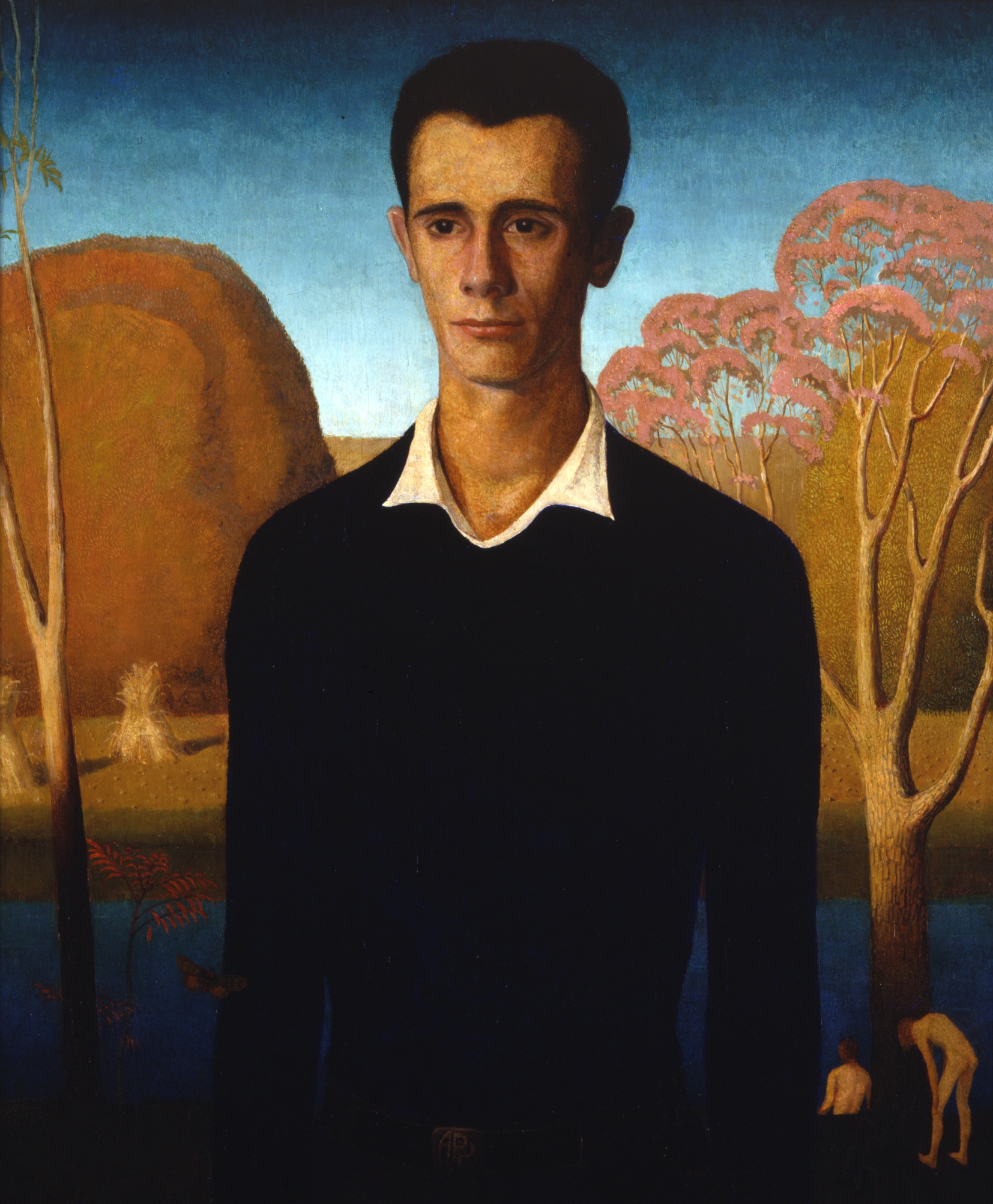

Wood and Arnold Pyle spent their days in the studio inside his small house, watched over fastidiously by Nan and Hattie (then in her seventies). One of Wood’s first paintings after his artistic breakthrough was Arnold Comes of Age, which Wood created as a loving gift for Arnold’s 21st birthday. In one of his last appearances in Chicago, Wood admitted that he poured his emotions and longings into his art. Arnold Comes of Age, which on surface appears to be just one of his new Regionalist portraits, is a perfect example. One of the only three portraits that he created out of love in his career (the other ones being of his mother and his sister), Wood’s gift reveals his desire for Pyle in a coded way. Its melancholic mood expresses Wood’s sadness at being unable to consummate their relationship.

There is a theme of couples in the painting (two trees, two haystacks, two bushes), alluding to his yearning for Pyle. The painting brims with intimate images, which Arnold would have been able to decode. Pyle’s dark sweater casts a gloomy shadow on two nude young men skinny-dipping in the corner, evoking Adam and Eve expelled from paradise. In the painting, where one of them thrusts his buttocks backward provocatively, they have become Adam and Adam, far away from the prying eyes and the laws that could have sent Wood to prison for up to ten years had his feelings for Pyle become widely known.

To the left, a butterfly lands on Pyle’s sleeve. The traditional interpretation would be Arnold’s transformation into a mature man, but this visual has many layers. The Butterfly Teashop was their favorite hangout in town, and just as a butterfly camouflages its beauty from predators, Wood had to do the same as a gay man. Wood signed his name next to Arnold’s belt (probably crafted by Wood), featuring Arnold’s initials, so that, at least in his painting. they could be together forever.

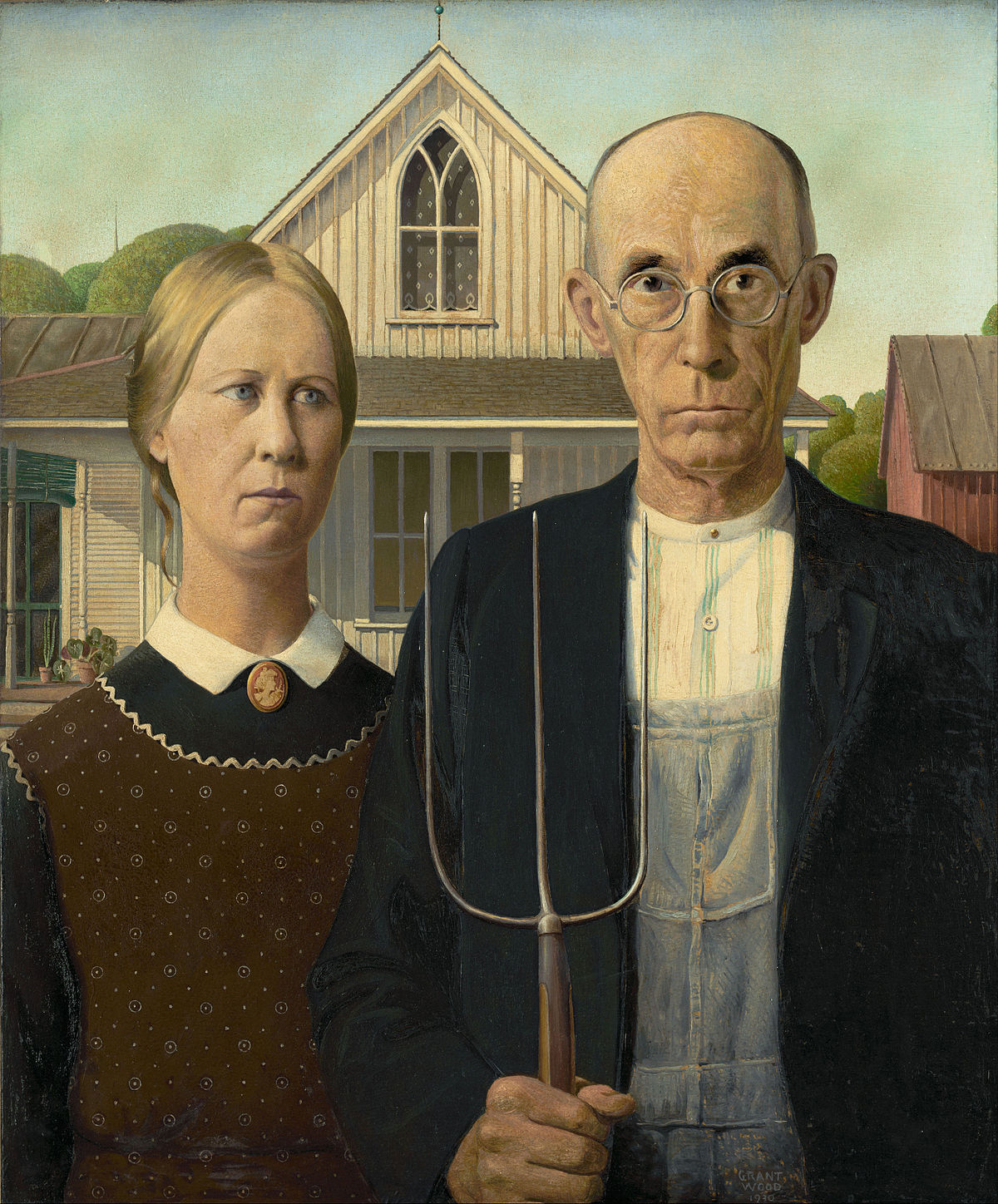

Nineteen-thirty was a banner year for Wood. In addition to Arnold Comes of Age, he painted American Gothic, which turned him into an instant celebrity. There are only a few paintings that are recognizable around the world: Leonardo’s Mona Lisa is one; American Gothic is another. They both share the enigmatic expression of their subjects, provoking an inquisitive reaction in viewers.

On a teaching trip to Eldon, Iowa, Wood became entranced with a small house, built in Carpenter Gothic style, with a window that mimicked the windows in European cathedrals. He decided to create a painting with two figures standing in front of it, a pitchfork-wielding farmer and a stern, black-clad woman, both featuring elongated faces to match the window. Nan, who was thirty at the time, modeled as the woman, wearing their mother’s outmoded clothes. Wood’s dentist, 62, posed separately as the farmer.

The painting was an immediate sensation. Its subversive and ambiguous possibilities elicited a barrage of questions. Were they father and daughter? Husband and wife? If so, why was he so much older? Some critics described it as a bedrock of American values, while others accused it of mocking rural life and of being creepy (after all, it was created at a funeral home).

Wood allowed the controversy to brew because it stirred publicity and interest. A Boston critic stated: “Wood must have been tortured by these people, who couldn’t understand the joy of art within him and tried to crush his soul.” He may have been on to something. Considering that Arnold Comes of Age was created at the same time, it’s not farfetched to suppose that what American Gothic truly depicts is Wood being watched like a hawk by his sister (wearing their mother’s clothes), with Wood’s dentist as his alter ego.

Time magazine hailed Wood as the inventor of “a truly national art.” Gertrude Stein called him “the first artist of America,” because, “before him, American artists simply imitated the European ones.” For Wood, a man with a secret, sudden celebrity was a mixed blessing. Major publications described him as “a shy bachelor’’ who maintained “a discreet silence about marriage,” while mentioning his high-pitched voice—obvious allusions to his homosexuality. Fame also brought unwelcome guests, including visitors who stormed in clamoring to see Wood’s family eating and sleeping and even a young man who blackmailed Wood for reasons that are never clarified.

Taking a respite, Wood founded the Stone City Art Colony, where he spent time with a homosocial crowd of students and teachers away from his family’s supervision. For two summers, Wood fostered local artists and shared uninhibited days, as well as the ice wagon he slept in, with Pyle, who became a Regionalist artist in his own right.

In 1935, Wood’s mother died, causing an acute crisis. Unable to justify any longer his bachelorhood with the excuse of taking care of her, Wood quickly married Sara Sherman Maxon, a former opera singer seven years his senior and already a grandmother. Friends and family were not—to their astonishment—invited to the ceremony.

A progressive, larger-than-life personality, Sara, who described the sex in her first marriage as repellent, didn’t care about her husband’s sexuality. In her diaries, she compared him to Oscar Wilde: “a genius in spite of the reasons behind his final degradation.” She took over Hattie’s domestic duties and treated Wood like a child who needed looking after. Rejected by Cedar Rapids’ uptight society, they move to Iowa City, where Wood got a teaching position at the university. Sara’s deadbeat 28-year-old son Sherman, his wife, and daughter moved in with them. Following his usual pattern, Wood was immediately smitten with the handsome young man, lavishing money and attention on him and nearly adopting him. In revenge, Sara made Wood wear dandy clothes. Getting defrocked from his overalls became Wood’s kryptonite, ushering in his decline as an artist.

Wood then hired the dashing 23-year-old Park Rinard to coauthor his autobiography. His constant presence at home made Sara hugely unhappy. Although not gay, Rinard recognized Wood’s attraction to him. The Regionalists had provided Wood with a masculine cover, but he remained closeted because the group’s leader, Thomas Benton, whose early career had been championed by gay supporters, was wildly homophobic. Wood sublimated his repressed desires in homoerotic paintings containing camp humor and double meanings, daring the viewer to decipher them.

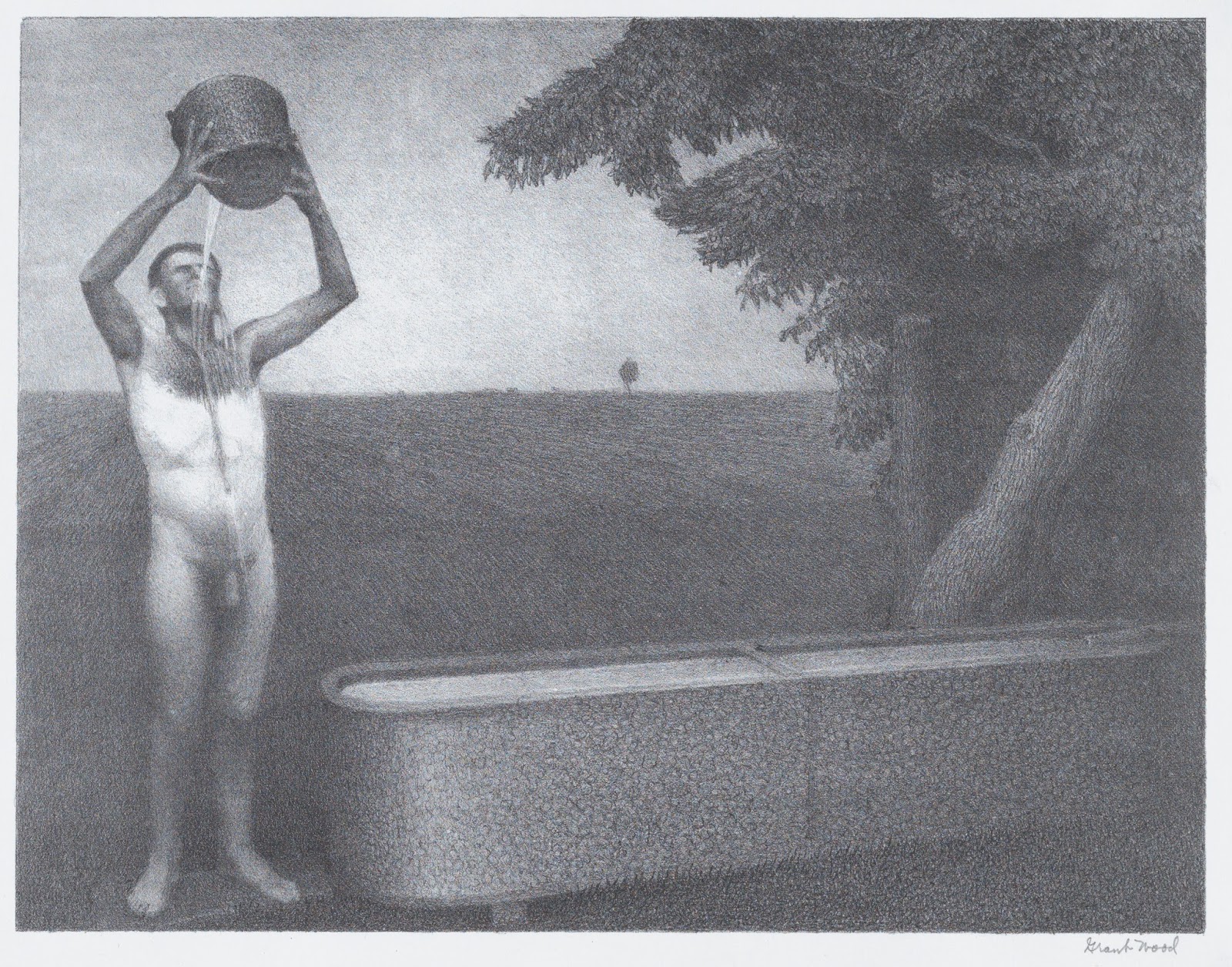

Following Stone City, a painting that conceals the tip of a giant penis hiding in plain sight (see article in the March-April 2015 issue) in 1936, Wood created his only major painting during his marriage, Spring Turning. Ostensibly a farming landscape with rippling hills, a closer inspection reveals the massive contours and sensual back of a male farmer wearing overalls. It was attacked in the press as “queer,” but Wood couldn’t stop himself. He produced the lithographs titled Fertility, featuring a penis-like silo, and Sultry Night, in which a farmer pours water over his naked body, next to a phallic trough. In an astonishing act of self-erasure, when the U.S. Postal Service refused it on the charge of obscenity, Wood sawed off and burned the nude from the painting that was the basis of the lithograph, never producing a male nude again.

Wood and Sara’s marriage, based on friendship and convenience, ended acrimoniously after less than four years. When Sara was taken away in an ambulance, Wood, who was mowing the lawn, kept at it, unfazed. They never saw each other again, and Park Rinard moved in immediately, causing an unexpected ripple effect. Five university colleagues filed a complaint against Wood. World politics had changed during World War II, and Regionalism was now considered a nationalist or even fascist style, akin to Nazi propaganda art. Wood was openly charged with “being a homosexual with a strange relationship with Park Rinard.” One accuser purposely excluded Wood from his History of Art, which would become a standard textbook. To decompress, Wood traveled to Key West, where he visited gay bars with Tennessee Williams, who described him as “very, very friendly.”

The charges were eventually dropped, and Wood kept his job, but the ordeal wreaked havoc on his health. In 1941, he became seriously ill with pancreatic cancer. Delirious from morphine, he told his sister that he wanted to move to Palm Springs, where she should “be on the lookout for an Oriental houseboy.” He died hours before his 51st birthday. R. Tripp Evans’ splendid biography of Wood reveals that his last word was “Nan.” Park Rinard was Wood’s only companion at his final moment.

Epilogue

After leaving Grant Wood in 1935, Arnold Pyle combined painting with advertising in his work. In 1973, he attended the first Grant Wood Art Festival in Wood’s birth town, Anamosa. Pyle died in an automobile accident traveling back to Cedar Rapids.

Despite Nan’s encouragement, Park Rinard never finished Wood’s biography, in all likelihood because the facts would have conflicted with the myth that Wood had created. Rinard became a tireless advocate for gay rights in the 1960s, at a time when that was extremely brave. We can only guess that he did this as a tribute to his dear friend, Grant Wood.

After their divorce, Sara Sherman worked as a cook and housekeeper for two decades, then moved to Los Angeles and New York City to break back into show business, unsuccessfully.

Nan Wood died at 91, 48 years after her brother. She relished being a minor celebrity, woefully unaware that when Wood painted her as the spinster daughter in American Gothic, she was the symbol of all that hemmed him in. In her loving biography of her brother, Nan denied his homosexuality, ignored his relationship with his assistants, relegated Arnold Comes of Age to a paragraph, and perpetuated myths about his female lovers. She continually sued biographers who “attempt to slur her brother’s good name” and burned Wood’s personal letters because “they are unimportant.”

Grant Wood had a significant impact on American art, influencing future movements such as Pop Art. Ninety years after its creation, American Gothic is still one of the most widely reproduced—and parodied—works of art in the world.

Ignacio Darnaude is an art writer, lecturer and film producer. He is currently developing the docuseries Hiding in Plain Sight—Breaking the Queer Code in Art

Here’s a thought: What if…the official version is true and we don’t have to make everyone gay? Some people are just weird.

Great read // thanks.

What an exhilarating article! Reading about Grant Wood’s queerness has made me understand and appreciate his work even more. I got goosebumps reading that the Whitney Museum said that Wood’s queerness is the key that unlocks the truth to his art. In reactionary, anti-gay times like ours, stories like this, revealing how gay artists have transformed art history are essential. Bravo! Thanks, Wehoville for publishing it.

I love these little nuggets of art history. I knew next to nothing about Grant Wood other than being familiar with his painting, “American Gothic,” and it increases my interest in seeing more of his work. Much more to explore.

It appears that “Art Historian” has been removed from the thumbnail resume. That is good since it also appears that the author’s conflicted sensibilities take great liberty with and superimpose his conflicts on artists throughout history with a considerably narrow lense thus rejecting scholarly information.

Supposition is one person’s opinion but can achieve monetary goals by dispensing salacious perspectives. People can be infinitely gullible.

It’s so sad that people with a narrow lense like you refuse to acknowledge that an artist’s queerness impacts their work intimately, as this article shows in a spectacular way. That’s why articles like this are essential. If you have a different perspective, instead of criticizing from the balcony like the old farts in the Muppet Show, write your own article and publish it, we’d love to read it

Unfortunately you missed the point, that was neither stated not implied.

The splendid article mentions how the Whitney Museum retrospective of Grant Wood declared that his homosexuality is the key that unlocks the code to his art. Are you trying to say that the Whitney curators didn’t know what they were talking about and you know better ? You sound like Grant Wood’s sister, covering his homosexuality for decades after he died and burning his letters “because they were not important” We’ve had enough of homophobes like you. Time to move on and listen to the true scholars like the ones at the Whitney.

Additionally, Mr. Daraude has chosen a narrative upon which he has narrowly selected points to support himself. That practice is not a scholarly review and is not peer respected theory. Mr. Daraude caught my attention by initially speculating about Michelangelo, a subject about which I know a thing or two having extensively studied with one of the preeminent scholars on the subject. To my knowledge he never addressed any of the comments other than oddly defensive remarks under other name(s). He has also apparently liberally spread his speculations through lectures and articles presenting it as fact which it is not.… Read more »

I guess your theories are accurate but the Whitney curators indicating that Wood’s homosexuality was key to his work is “narrow and not peer respected theory”? What you describe as “narrow” is, actually, the opposite, expansive. This article has helped me understand Grant Wood and his work deeply. Your comment is what we usually hear from homophobes when one tries to discuss the impact of an artist’s queerness in their work. Your true colors are showing and nothing you say will change that. You keep referring to yourself as an expert “studying with preeminent scholars” If that’s the case, enlighten… Read more »

Twisting what was stated will not help your POV. Never indicated being an expert, however more than well informed. Strange that Me. Day side does not respond or perhaps he is responding. Homophobia as your response is not accurate, it’s just troubling to see folks misrepresenting information. Facts are facts, impressions and tentative theories are something else.

Twisting what was stated will not help your POV. Never indicated being an expert, however more than well informed. Strange that Mr. Darnaude does not respond or perhaps he is responding. Homophobia as your response in inaccurate, it’s just troubling to see folks misrepresenting information. Facts are facts, impressions and tentative theories are something else entirely.

I would appreciate reading your perspective on Michelangelo. He, Da Vici and Raphael are among my favorite Renaissance artists, do share!

Profoundly relevant to American art, social history and the powerfully intimate revelation of the psyche of artists and their development along the often tightrope walk of social mores.

I absolutely love this article! Learned a lot about a painting and artist I love, and realize there’s so much to Grant Wood and his work than I ever knew. – particularly his queerness. So happy you are bringing this to light, and that WeHoVille is featuring it. How refreshing!

Amazing story!!! So wonderful that you can bring to light the artists who were not able to reveal their stories and the hidden symbols you connect are unreal.

What an AMAZING article. It makes me understand this iconic painting from a completely different, and more accurate point of view, and it reminds us of the huge impact of queer artists in history and the pain they went thru staying in the closet. BRAVO!

good grief