Republished with permission from the GAY & LESBIAN REVIEW. For more information and related articles, please check https://glreview.org/

A traveling exhibition titled Breaking the Rules, now at Memphis’ Dixon Museum, presents an enlightening narrative about the groundbreaking work of two remarkable gay artists: Paul Wonner and Theophilus Brown, who ignited an artistic flowering known as the Bay Area Figurative Movement from their Berkeley studio. Wonner and Brown, whose 56-year relationship was forged during the McCarthy era, did break many rules, but they paid a high price for it. Their tendency to focus on the male figure discouraged critical attention and commercial success. Only now, through this retrospective, is their artistic contribution being duly recognized.

Paul Wonner (1920–2008) and William “Theophilus” Brown (1919–2012), despite being recognized as Bay Area artists, hailed from Tucson, Arizona, and Moline, Illinois, respectively. They met in 1952 while pursuing a master’s degree in art at UC-Berkeley, and the rest is history. And yet, they had very different personalities. Wonner, who was shy and soft-spoken, thought the gregarious Brown was a bit of a snob, and he had a point. Brown graduated from Yale and had mingled with influential cultural figures like Picasso and Stravinsky during the postwar years, when Elaine and Willem de Kooning took him under their wing.

It wasn’t love at first sight. It took six weeks for Wonner to invite Brown to his apartment for lunch, a simple gesture that catalyzed a profound personal and artistic partnership that lasted five and a half decades. Living openly as a gay couple during the perilous climate of 1950s America posed significant personal and professional risks. A 1953 Executive Order barred homosexuals from employment in the federal government, resulting in numerous dismissals and the outing of thousands without legal recourse.

These prosecutions had a chilling impact on the art world, forcing most gay artists to abandon homoerotic imagery and figurative art altogether. Queer artists had to adopt strategies of concealment during this period to survive. This is when Abstract Expressionism was the dominant American school, and it provided a convenient outlet. Artists like Ellsworth Kelly and Agnes Martin avoided scrutiny by living discreetly and creating exclusively abstract works. When Bay Area artist Richard Caldwell Brewer dared to create explicit homoerotic imagery, he paid the ultimate critical price: complete erasure of his work. Another San Francisco artist, Bernice Bing (1936–1998), had three strikes against her as a queer Asian woman; only now is she getting the recognition she deserves.

Wonner and Brown shared a studio in Berkeley that became the nerve center for an artistic revolt against the repression of the times. It all started the day the artist Richard Diebenkorn, who also had a studio in their building, showed up freezing at Wonner and Brown’s door, asking if they had a heater. Wonner and Brown’s studio was large, and they invited him in. It was around this time (1955) that Diebenkorn and other artists—such as Elmer Bischoff, David Park, James Weeks, and Nathan Oliveira—began to gather for drawing sessions centered on the human figure at Wonner and Brown’s studio. Brown relished these sessions because he experienced a camaraderie very different from the vibe in New York, where he felt only rivalry among the up-and-coming artists.

This creative association gave birth to what came to be known as the Bay Area Figurative Movement, which challenged the dominance of Abstract Expressionism and offered an alternative trajectory. David Park was the first to break away when he trashed his abstract canvases at San Francisco’s city dump in 1949. His painting Kids on Bikes (1950), depicting two male figures, set the tone for what was to come: a resurgence of figurative art in place of abstraction. In 1957, The Oakland Museum mounted a groundbreaking show titled Contemporary Bay Area Figurative Painting, which put the movement and these painters on the map.

The title of the current exhibition, Breaking the Rules, also refers to Wonner and Brown’s frequent depiction of male nudes, despite galleries’ reluctance to “sell anything with a penis.” Brown persisted because “his mission was to bring parity to female and male nudity in galleries and museums.” His male nudes, including his daring self-portraits, are the most overt manifestation of his sexuality, but—perh=

Joint exhibitions of Wonner and Brown’s work faced rejection until 1999, when Wonner was 79 and Brown was eighty. The reluctance stemmed from fears of alienating potential buyers due to nature of their relationship. The prudery of the early days compelled them, like numerous contemporary artists, to embed queer themes in their art through creative subterfuges and coded imagery that could be recognized by gay viewers (and a few others) while eluding everyone else.

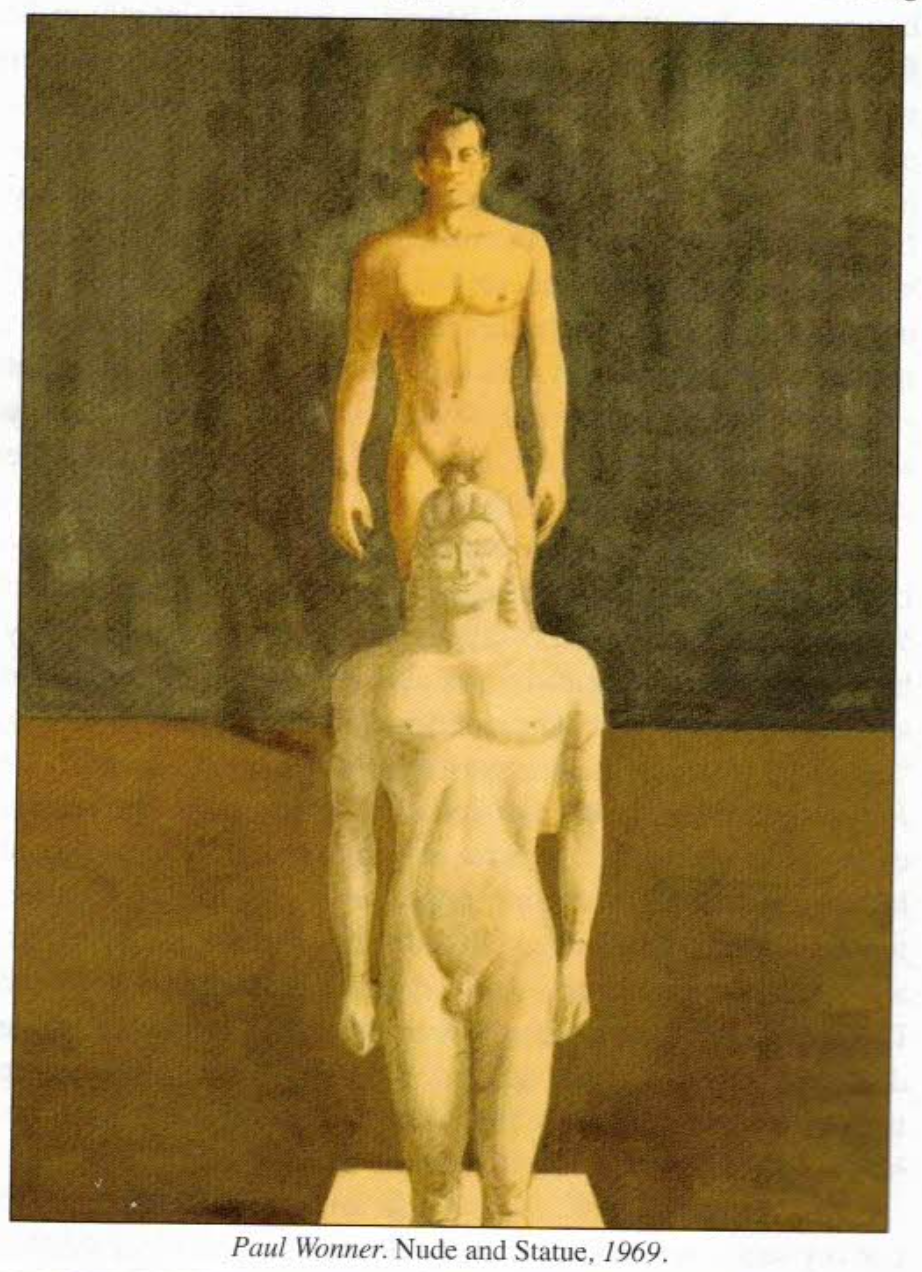

Classical imagery provided an ideal cloak for their homoerotic expressions. Wonner’s depictions of Greek sculptures with harmonious proportions allowed him to show his appreciation of the male form with impunity. Brown’s surreal and ambiguous homoerotic classical imagery, often untitled to encourage varied interpretations, navigated a delicate balance between visibility and defiance. Both artists also created mythological images, another popular trope with which to depict alluring males on the pretext that their nudity was taking

place in the realm of fantasy. Wonner’s 2007 painting Five Models as Bacchus is a great example.

Their portrayal of nudes in arcadian settings, a long-standing tradition among gay artists and writers, also hinted at same-sex desires. Wonner created his own version of Arcadia in a series of modern-day park scenes in which male figures enjoy an environment of absolute peace and freedom, a gay paradise. Meanwhile, Brown’s arcadian images celebrated hetero- and homosexual relationships alike in scenes that he called “Fantasies of a beautiful, harmonious world. Brown created dreamlike or surreal scenes in settings such as beaches, which provided a pretext for nudity. He got inspiration from photos of nudist magazines, which were cheaper than paying a model and featured people interacting.

Christian images were also a common smokescreen. Wonner created multiple sensual images of angels, Saint Sebastian, St. John of the Cross, and even Christ—in a scene in which he’s tempted by a naked man. He also gave Daniel in the Lion’s Den a homoerotic twist, portraying Daniel as young, beefy, and naked. Most of these mystical scenes have a tinge of surrealism that encodes their obvious homoeroticism.

Both artists also mastered the art of hiding gay imagery in plain sight. Early in his career, Brown painted football scenes infused with male intimacy. What’s fascinating is that Brown didn’t know anything about sports. When Life magazine ran an article about these paintings, the writer noted that “Brown was unconcerned with the tactics of a game, even putting a same-colored jersey on members of opposite teams.” He was right; all Brown cared about was men in close quarters in a way that was acceptable to heterosexual viewers.

Brown, who was the most symbolist artist of the Movement, infused his work with tension and a sense that there’s more here than meets the eye. The totemic figures in his arcadian compositions are not distinct individuals but archetypes imbued with psychological and sexual undertones. The poses in Nude Figures on a Beach with Horse and Dog (1986) create a charged atmosphere in which intimate connections are established among certain figures while male nudes are presented as outsiders, reflecting his personal journey as a gay man. Once again, critics avoided discussing their homoeroticism, choosing to highlight instead how “the human figure seamlessly integrates into nature.”

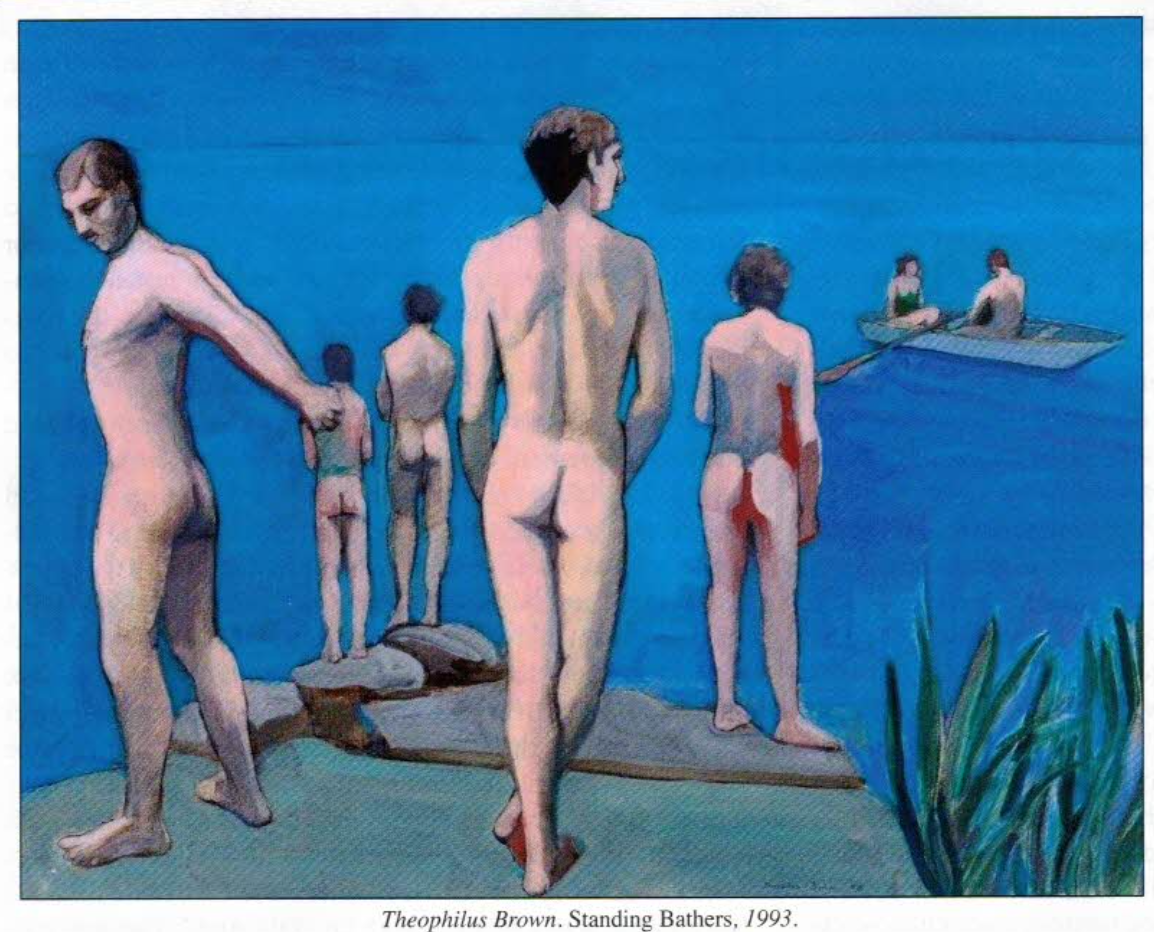

Wonner and Brown frequented Yuba River, indulging in naked swims. Wonner’s paintings of nude bathers went unquestioned because they aligned with the established tradition of men bathing together. Drawing inspiration from Paul Cézanne, Wonner portrays the bathers as a dynamic mass of interwoven, predominantly male figures. Wonner sent a touching Christmas card to Brown in which he referred to himself as “Paul Cézanne,” an acknowledgment of the influence of the French artist on their work. In contrast to Wonner’s

approach, Brown’s bathers, such as “Standing Bathers” (1993), which is the official image of the exhibition, stand as iconic, solitary figures within a surreal frieze reminiscent of classical and neo-classical artists. David Park, another member of the Movement, also explored nude bathing motifs that exuded sensuality but avoided overt eroticism. While they may seem tame to our eyes, Park’s portrayal of male nudes amid the stifling atmosphere of the 1950s was an act of defiance.

Early in their career, Wonner and Brown came to the conclusion that the division between abstraction and figurative art was largely arbitrary. Rather than eliminate one or the other, they broke artistic boundaries by fusing these seemingly disparate styles into a new form of painting which, in Wonner’s words, “offered a psychological experience.” A case in point is River Bathers (1961), in which the semi-abstract features of two sitters engaged in an ambiguous relationship allow Wonner to hint at homosexuality, providing a glimpse into his world while keeping us at a distance. Their prolific depiction of swimming pools, a motif they explored upon moving to Malibu in 1963, predated David Hockney’s iconic pool paintings. What’s more, their style diverged sharply from that of Hockney with his inviting turquoise waters. Compare that to Brown’s foreboding, shadow-laden scenes in works like Swimming Pool (1963).

Wonner and Brown employed an array of coded imagery to convey same-sex desire, such as flowers, a historical symbol used by queer artists to represent unspoken desires. A well-known example is the green carnations that were used by gay men during the Oscar Wilde era to identify one another. By the end of the 1950’s, Wonner began painting male nudes holding flowers. In these coded images, he subverted the aggressive masculinity of the Abstract Expressionists (think Jackson Pollock), offering a portrayal of virility that was gentle, vulnerable, and sensual. Another example, and one of his best-known paintings, is the large triptych Seven Views of the Model with Flowers (1962), which can be interpreted as another one of his arcadian landscapes or even as a religious image. All seven men have halos, echoing Jesus and his disciples.

Wonner’s œuvre includes frequent coded images of pansies. The word “pansy” is, of course, one of many anti-gay slurs. In his striking French Still Life (1990), a vase with pansies stands proudly above books depicting French and English artists, implicitly claiming that queer artists are at the top of the artistic canon. His landmark painting Glasses with Pansies (1968) portrays two isolated and distant pansies, mirroring the sense of isolation felt by Wonner and Brown.

Despite the tight-knit nature of their Movement, both artists knew that, as a gay couple, they would always remain outsiders to some degree. This fact inevitably impacted their work, infusing it with imagery of absence and isolation. Wonner and Brown moved to Santa Monica

in 1961 when Wonner became an art instructor at UCLA. They took morning swims and, while this should normally be a joyful activity, Brown’s painting Muscatine Diver (1963) depicts a somber landscape and an ominous sky, with a sense of disconnection as one man turns away from the other. Wonner frequently portrayed empty chairs, a recurring motif symbolizing loss.

In 1962, the two artists developed a close friendship with writer Christopher Isherwood and his partner, artist Don Bachardy. Their weekly gatherings for conversation and sketching often took place at Isherwood’s home. Works from these sessions are difficult to identify, given Wonner’s tendency to title pieces using only initials, possibly to widen their appeal or to conceal the identities of their social circle. For instance, Wonner cryptically referred to Brown as “W. B.,” and, in the enigmatic portrait Living Room at I’s (1964), the “I” refers to Isherwood. The unfocused faces in this painting allow for varied interpretations—potentially representing Isherwood and Bachardy or perhaps even Wonner and Brown themselves.

Upon their brief return to Berkeley in 1974, Brown created provocative artworks portraying explicit homosexual and heterosexual acts, which remained unseen in public until the 1990s. Wonner sought solace in literature to better understand his identity as a gay man, finding resonance in Walt Whitman’s writings. His tribute series to Whitman includes American Men Thinking of Walt Whitman (1975), which features burly men under a rainbow, three years before the rainbow flag became the symbol of the LGBT community.

In 2001, Wonner faced physical challenges when his back gave out, prompting their move to a seniors’ residence in San Francisco. During this period, Wonner delved back into the male form with a series titled “Youth and Old Age.” Through intimate gouaches, he fearlessly tackled aging and mortality, starkly contrasting portraits of himself, clothed and aged, with nude, youthful male models. Commented Wonner: “I feel that they are both me. The art connects us.” The way the poses of artist and model mirror each other underscores this connection. According to Brown, Wonner created these self-portraits as a way to be remembered for posterity.

The images created by Wonner and Brown are not their only legacy to the LGBT community. They donated over 1,800 works to the Crocker Museum in Sacramento, to be sold with proceeds supporting acquisition and exhibition of art by emerging LGBT artists, thus leaving a lasting gift of support for the community’s artistic endeavors.

Wonner once remarked: “Being gay was the greatest thing that ever happened to me. It gave me a direction that I might not have had otherwise and made me not afraid of being an outsider and being by myself. It also gave me a lot of courage to just blunder ahead and do things.” Theophilus Brown declared: “Because of the constant opposition under which we live,

we become very strong. We look deeper into things because we are forced to. In a way it’s a great privilege. I would choose to be gay if there had been a choice at all.”

Wonner and Brown were influenced by many artists, but clearly they were each other’s most important inspiration, even while also remaining independent in their work. When Wonner died in 2008, Brown declared: “Paul was the most central person in my life. He was also my best critic and I think I was his. When I did something that wasn’t very good and I wanted reassurance, I didn’t get it from Paul. He was always honest. I think that’s what I miss the most.” Brown lived four more years, creating art until the very end. I want to believe that, thanks to the excitement around this exhibition, they’ve finally become the heroes of their own stories.

Ignacio Darnaude, an art scholar, lecturer, and film producer, is currently developing the docuseries Hiding in Plain Sight: Breaking the Queer Code in Art.

Paragraph seven – the last sentence of it is cut off.

Where is the rest?

Interesting article.

Thank you.

—perhaps because few of them depicted male-to-male contact—critics sidestepped their homoerotic implications.

WOW! I knew the work of Wonner and Brown from a recent retrospective at the Laguna Art Museum but I didn’t know about their amazing story and 50-year relationship, which this article brings to life in a magnificent way. Thanks so much for an inspiring and moving story about our community.