In this article for the GAY & LESBIAN REVIEW, Ignacio Darnaude discusses Federico Garcia Lorca’s intimate relationship with Salvador Dali, shedding light on Lorca’s vivid portrayal of queer desire in his writings and drawings alongside Dali’s provocative surrealist masterpieces, which subtly hint at his own exploration of sexual identity. For more information and related articles, please check https://glreview.org/

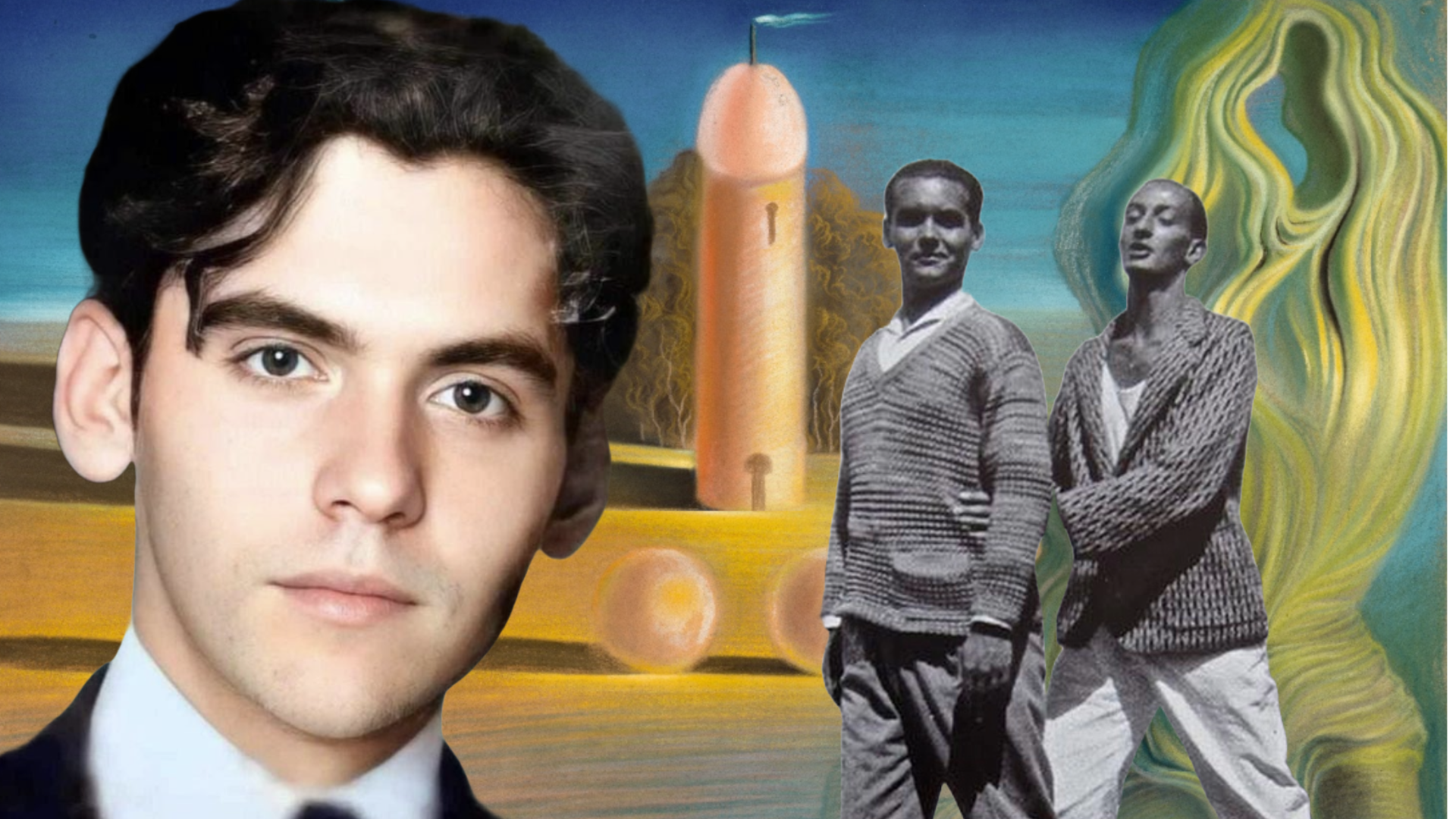

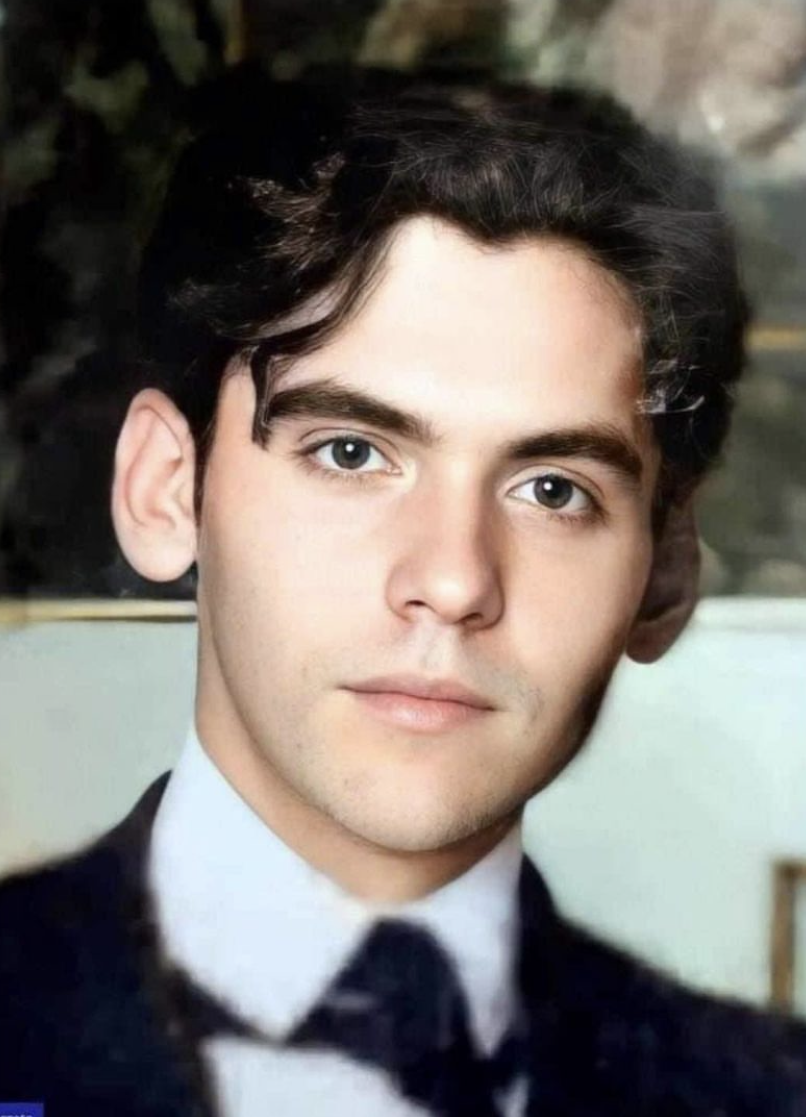

In the heart of Madrid, amid the vibrant cultural hub of the Students’ Residence, fate orchestrated a meeting in 1923 that would forever alter the trajectories of two towering figures in Spanish culture: Federico García Lorca (1898-1936) and Salvador Dalí (1904-1989). Lorca would soon become one of Spain’s most important writers and poets and a universal queer icon with timeless classics such as Blood Wedding (1932) and The House of Bernarda Alba (1936). Dalí would turn into a world-renowned surrealist painter. This is the story of their extraordinary relationship, an impossible love story for the ages.

Having been born just three years after the Oscar Wilde Trials, which imprinted homosexuality on the social consciousness of Europe, Lorca struggled with his homosexuality, which became a constant source of anguish. As a youngster, a teacher called him Federica for not being boyish enough. At the age of twenty, he wrote to a friend confessing that “in the presence of others I feign a sexual leaning that isn’t in my heart’s truth.”

Lorca grew up at a time when homosexuals could be imprisoned in Spain for up to twelve years. This changed dramatically under the 1932 Republican Penal Code, which only penalized homosexuality in cases of abuse. Spain’s social reality, however, didn’t live up to the new legislation. When Lorca became the artistic director of La Barraca, a theater group that brought classical Spanish plays to rural audiences, a right-wing critic called him “a faggot surrounded by a nest of homosexuals.” It’s no surprise that Lorca always dreamed of leaving Granada and Spain’s suffocating sexual morality.

Like many queer artists before and after him, Lorca used coded language that allowed him to share his unique life experience in a way that passed unnoticed right under the gaze of intolerant observers. Lorca’s dance of veiled metaphors gave birth to his most personal, intimate, and innovative works. Many of his plays are coded allegories about the repression of sexuality. The Butterfly Curse (1920) is a barely concealed expression of his sexual yearnings. The cry for sexual freedom in Blood Wedding implies that to deny your sexuality is tantamount to dying. The other theme in Lorca’s plays is unfulfilled desire for something one can’t have. In Once five years pass (1931), a woman longs to marry a closeted gay man. Yerma (1934) is about a woman’s desperate desire to have a child. The title character in Doña Rosita the Spinster (1935) dreams of having a boyfriend, while The House of Bernarda Alba tackles five sisters’ desire for freedom from a tyrannical mother.

Lorca centered many plays on women because he loved spending time with them and he couldn’t write openly about men’s desires. In doing so, he anticipated queer writers such as Tennessee Williams whose female characters experience the same persecution that he experienced in a patriarchal and sexist culture. But there’s also overt homoeroticism in Lorca’s literary work. Gypsy Ballads (1928) is a book of poems that joyously celebrates male beauty and virility. In Lament for Ignacio Sanchez Mejias (1935), another poetry collection, he proclaims his admiration for larger-than-life men such as the title bullfighter.

A watershed moment in Lorca’s life came in 1919 when he joined Madrid’s Students’ Residence, a cultural institution that welcomed Spain’s brightest young thinkers, writers, and artists, exposing them to progressive ideas from abroad with the goal of forging the leaders of modern Spanish society. But even in this progressive environment, Lorca found that it was difficult to be gay. He knew that some students avoided him because of his “defect,” and he used his talents as an artist to counter this rejection. He could gather a crowd with his hearty laughter and funny stories, or with his skills at singing and playing the guitar and piano. One of those who fell under his spell was film director Luis Buñuel. They became inseparable despite Buñuel’s open homophobia. In his autobiography, Buñuel says that he loved to beat homosexuals outside of Madrid’s public urinals.

Surrealist painter Salvador Dalí joined the Residence in 1923. Desperate for attention, he let his hair grow and glued it to his skull with varnish and used his mother’s eyeliner to make himself look like Rudolph Valentino, the silent movie star who represented the ideal of male beauty at this time. Lorca was dazzled by Dalí’s eccentricity and enigmatic allure. The fascination was clearly mutual. After Dalí first laid eyes on Lorca, he wrote: “The ultimate poetic phenomenon suddenly emerged before me in sublime flesh and blood vibrating with a thousand fireworks.”

Despite their divergent personalities—Dalí was very shy, while Lorca was described as “a fountain of laughter and music”—and even though Lorca was 25 years old and Dalí just nineteen, they became instant friends, united by shared passions and struggles. They were both anticlerical, champions of social justice, and artistically ambitious. And both had a rather complicated relationship with their sexuality.

Dalí’s favorite place on Earth was his family home in the idyllic Catalonian seaside town of Cadaques. Dalí invited Lorca to join them during 1925’s Easter break. Dalí’s parents and his seventeen-year-old sister Anna Maria embraced Lorca with the kind of love that he never received from his own family. Then the unexpected happened: Lorca fell madly in love with Dalí. The infatuation was apparently mutual, as Dalí’s paintings from that period depict Lorca obsessively.

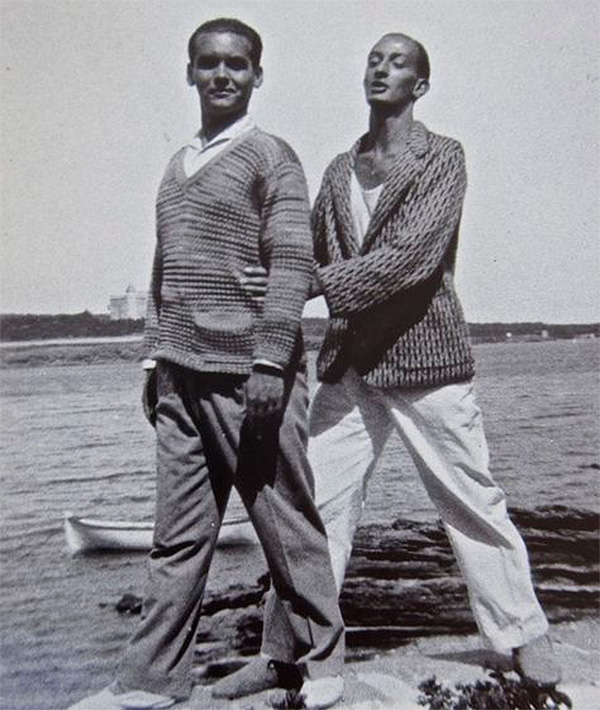

Lorca was convinced that Dalí was also gay but afraid to accept it. He tried to seduce Dalí with a long poem titled “Ode to Salvador Dalí” (1926) in which he addresses him as “Dalí of the olive-skinned voice” while imagining them living together as a couple. In his letters, Dalí calls Lorca “His little Federico” and signs them: “With all the tenderness of your little child Dalí.” Few letters from Lorca to Dalí remain, alas, because Dalí’s future wife Gala destroyed them out of jealousy. The photo in which Lorca places his hand lovingly on Dalí’s knee, however, leaves no doubt about the intimate nature of their relationship.

To understand the complexity of this bond, we need to address Dalí’s ambiguous and elusive sexuality, which found frequent expression in his paintings. His fear of sex started in childhood. His father left books around the house showing macabre photos of people with venereal diseases, which traumatized Dalí and made him terrified of physical contact and of female genitalia. He portrayed himself in public statements as impotent and a virgin when he met Gala. “I tried sex once with my wife Gala,” he reported. “It was overrated.” He began living with Gala in 1929, the year that he created his iconic painting The Great Masturbator, which reflects how, since he was a teenager, Dalí used masturbation as his sexual outlet “because it was more peaceful than making love” always followed by tears.

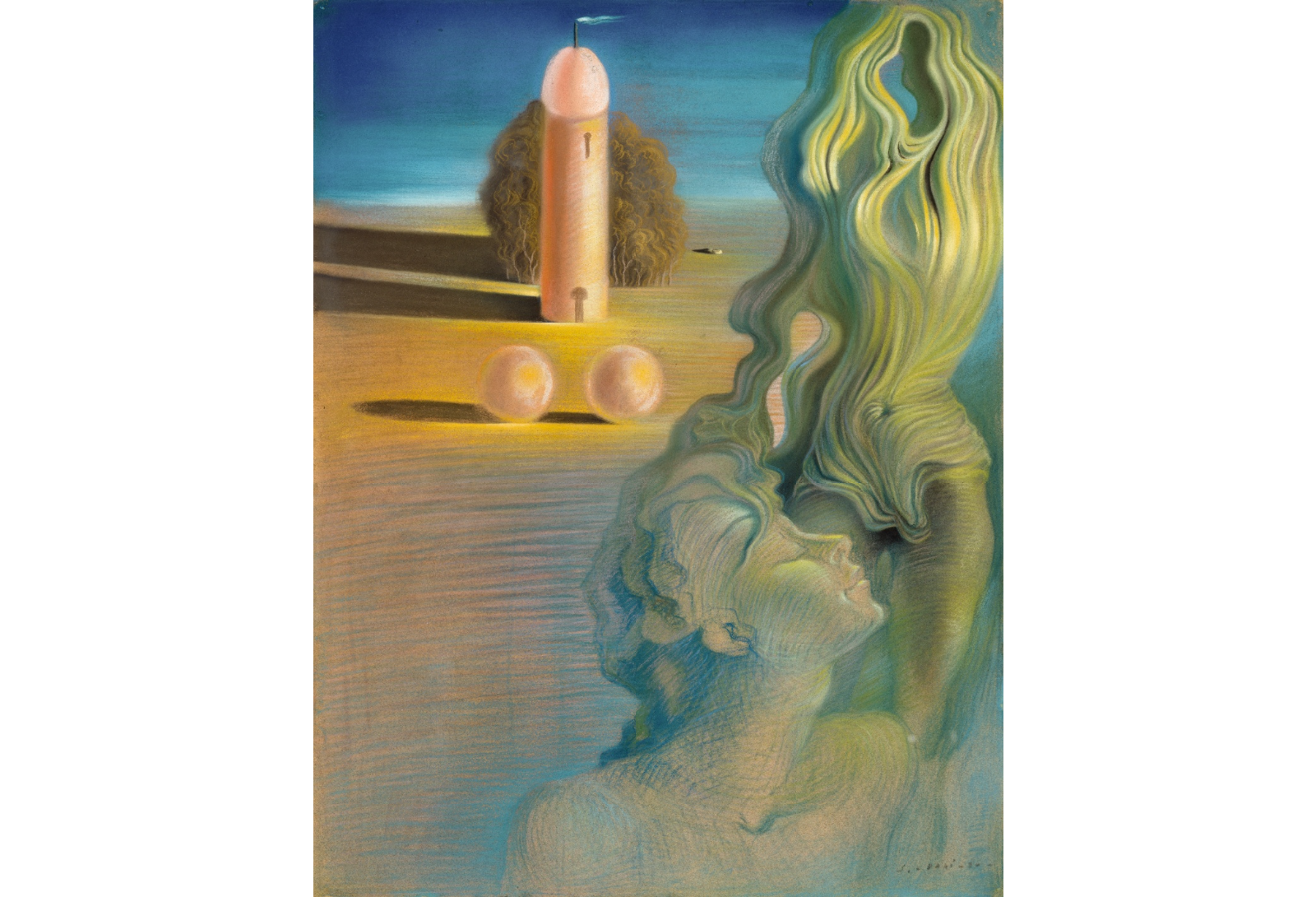

Beneath their heterosexual veneer, Dalí’s art simmers with possibilities. He painted many homoerotic images and was, according to his inner circle, attracted to men, the more androgynous the better. Gala was his shield against the specter of homosexuality, which he vehemently rejected in public, among other reasons because the leader of the Surrealist movement, André Breton, considered homosexuality to be an abomination. He was flattered by Lorca’s attention and constantly remarked on how handsome his friend was, but he recoiled from the physical intimacy that Lorca sought. In a famous interview, Dalí declared: “Lorca tried to have sex with me twice but I resisted because it hurt.” Maybe that’s what his “gay panic” painting Atmospheric Skull Sodomizing a Piano (1934) is all about

.

The extent and significance of Lorca’s homosexual orientation has come to light only slowly, long after the poet’s demise. Ian Gibson, a leading authority on the poet, revealed in his 1989 biography that until quite recently, Lorca’s family denied access to his archives to any researcher who wanted to explore Lorca’s sexuality. The poet’s siblings Francisco and Isabel published books about their brother avoiding any reference to his sexuality or to his explicitly queer work El Publico (1930). They also stopped a family friend from publishing letters revealing Lorca’s sexuality. After his death, the excuse was always the need to “protect his reputation” and “respect his privacy.” The second phase of the erasure was to pretend that his homosexuality had nothing to do with his work, stating that it was “irrelevant” and “morbid” to discuss it.

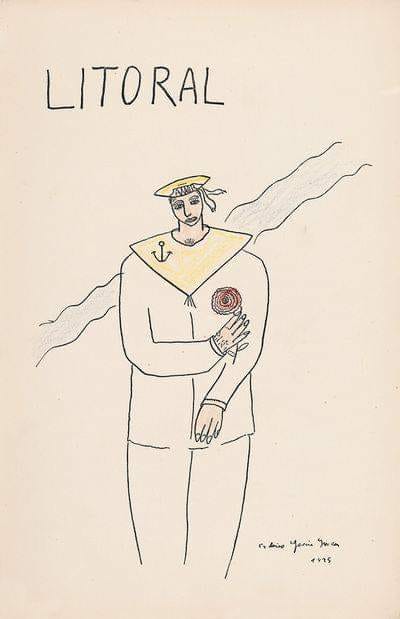

While Lorca rarely expressed his sexuality wholeheartedly in his poetry, he found an outlet in his drawings. His friend Gregorio Prieto said that “poetry was Lorca’s loyal boyfriend, but his drawings were a secret lover he was irresistibly attracted to.” There are almost 400 cataloged drawings. Most are small; many appeared in letters or books; some were gifts made for friends. Lorca said: “I feel clean, comfortable, happy, like a child when I draw.” He had no education as a painter and, while his images are unsophisticated, they project the same lyrical emotion and refined invention that his poetry exudes.

Lorca’s drawings, each line a whispered confession of his unspoken desires, are essential to understanding his poems and plays. Sometimes they express the germ of an idea that he would later elaborate in his literary work but the drawings always achieved full artistic autonomy. He manifested his homosexuality in drawings of marginal characters and victims of persecution like him, such as gypsies. He drew endless images of sailors, a popular trope for queer artists. They represent the underworld, characters who, after being on a ship for weeks, release their sexuality with absolute abandon. His sailor drawings envision a utopian world in which love between men occurs. The word “amor” (love) as well as an alluring bedroom appears in many of them. In one of his best-known images, a sailor oozing sadness holds a rose, reflecting Lorca’s absence of sexual expression.

Lorca joined the lineage of artists who used the myth of Zeus and Ganymede as a means to portray homoerotic images. He did it in a strikingly original way, linking this myth to his sailor imagery. He created an astonishing drawing while he was in in New York in 1929 in which a young, androgynous Ganymede-cum-cabin boy is grabbed by a rough Zeus/sailor while a woman screams at them, scandalized. Defiant images such as this that clearly embody Lorca’s homosexuality were a rarity in the Spanish artistic landscape of those years. He also painted androgynous harlequins, saints, and angels. When he painted a local sculpture depicting San Miguel as an ephebe dressed in lace to represent the city of Granada (in 1932), he received a huge backlash from city officers and friends such as Buñuel, who despised it.

Saint Sebastian became a crucial reference in the creative dialogue between Lorca and Dalí. Dalí admired the Saint’s erotic exhibitionism and sadistic desires. Lorca called it “the most beautiful figure of all the art that is seen with the eyes.” He sent Dalí two homoerotic drawings and a photograph of himself evoking this saint. Dalí responded with a cruel letter saying “Tied to a tree, Saint Sebastian’s ass doesn’t have a single wound,” alluding to their frustrated sexual encounter. Saint Sebastian became the homoerotic symbol of Lorca’s unfulfilled sexual longing.

One of Lorca’s most revealing drawings,”The Kiss” (1927), shows his self-portrait above which he includes Dalí’s likeness, their lips kissing. This is the clearest expression of Lorca’s desire for Dalí at a time when, not only was his love unrequited, but Dalí was moving to Paris to be with Buñuel, a fellow surrealist. Buñuel, who was fanatically jealous of Lorca and Dalí’s relationship, had finally succeeded in separating them. And if that wasn’t enough, Dalí started a relationship with his new muse Gala, which devastated Lorca. Dalí even publicly criticized Lorca’s poetry. The two would not speak again until a brief meeting in 1935.

Deserted by Dalí, Lorca began a fleeting relationship with the young sculptor Emilio Aladren. Though ostensibly heterosexual, Aladren fell under the spell of Lorca’s charisma only to abandon him for a beautiful woman in 1929, leaving Lorca adrift and in despair. He sank into a deep depression and lamented: “I deserve to be loved. I find in everything a painful absence of my true self, I need to go far away.”

Prompted by concerns for Lorca’s well-being, his father financed a journey to New York under the pretext that it would encourage his son to learn English. Arriving in June 1929, Lorca embarked on a nine-month odyssey that marked the dawn of a new chapter that included everything except learning English. Amid a bustling metropolis, Lorca struggled with profound loneliness. He wrote to his mother how he witnessed people jumping off the windows during the Wall Street crash that October. His unrest became the germ for the book of poems titled Poet In New York (1929), in which he called the city “the great lie of the world.”

Lorca explored his sexuality in the throbbing clubs of Harlem. However, his poems from this time show a profound internalized homophobia, inherited from his Spanish upbringing. At the beginning of his career, Lorca expressed disdain for what he called “the fairies of all nations.” He clashed with the effeminacy of the “fairies,” who were the most visible symbol of New York’s gay community at that time. These men challenged the sexual and gender protocols of mainstream society with a flamboyance that they presented as upper-class sophistication. For Lorca, having come from Spain, where the only type of homosexual known was the sissy, their behavior was unacceptable. In Ode to Walt Whitman (1929), he embraced what the queer poet described as “camaraderie love, manly friendships, fond, loving, pure, sweet, strong and lifelong” as his own sexual manifesto

Just when he was due to return to Spain, Lorca accepted an invitation to give a lecture series in Cuba, where he was received like a movie star. In the streets of Havana, embraced by a joyful and accepting culture, a language he understood, and music he adored, Lorca found sanctuary. The three months he spent in Cuba (March to June 1930) gave him a new lease on life. He took charge of his own destiny, living out his sexuality freely and starting to laugh again. He famously remarked: “If I get lost, let them look for me in Andalusia or Cuba.”

Buoyed by his newfound freedom, Lorca delved into his most audacious play yet, El Público, which he described as “frankly homosexual,” probably the first time he used that word openly. The focal relationship, a romance between an older and a younger man, allowed Lorca to explore daring themes such as gender transitioning, the entrapment of homosexuals, and homophobia in general. The protagonist, Lorca’s alter ego, envisions a future in which love between two men will be accepted. As Lorca predicted, the play would not be seen on a stage for decades. When it finally opened in Madrid in 1987, it became a sensation.

Back in Spain, Lorca fell in love with Rafael Rodriguez Rapun, who worked in his theater group La Barraca. Following a usual pattern, Rapun, a womanizer, was seduced by Lorca’s personality but didn’t reciprocate the poet’s passion, causing him tremendous grief. He wrote some of his daring and explicitly gay poems for Sonnets of Dark Love (1935) in Valencia while waiting hopelessly for Rapun. It took decades of public pressure for Lorca’s family to finally allow their publication. The Spanish newspaper that got the scoop in 1984 caved to Federico’s brother Francisco, who demanded that they be published under the title “Sonnets” or “Sonnets of Love” but under no circumstances with its original title, “Sonnets of Dark Love, even though there was no doubt that they were written for a man.

In the shadow of impending political upheaval, as Franco’s right-wing regime led a military uprising in July 1936, Lorca decided to leave Madrid to seek refuge in Granada, a decision that proved fatal. The actress Margarita Xirgu had offered Lorca to go to Mexico with her, but Lorca declined. According to some sources, Lorca did so because Rapun wasn’t able to join him. Others claim that Lorca wanted to be in Granada to be with his new lover, Juan Ramirez de Lucas, whose father denied him permission to travel abroad with the poet.

Be that as it may, Lorca went to Granada, where he was arrested on August 16, 1936, by a politician who said that “Lorca did more damage with his pen than others with the gun.” He was tortured while he was in jail and then executed. One of the executors went to a bar afterwards and announced out loud: “We just killed Federico Garcia Lorca. I fired two bullets into his ass for being a queer and left him in a ditch.” Lorca’s remains haven’t been found. His death at age 38 became an instant symbol of everything the Spanish right-wing regime was trying to repress.

Dalí and Lorca met briefly at the opening of Lorca’s Doña Rosita the Spinster in 1935. They told a journalist: “We haven’t seen each other in seven years but it seems like we never stopped talking.” When Lorca died months later, Dalí was tormented by guilt, regret, and the fantasy that he could have saved him. This is when Lorca became an obsessive motif in many of Dalí’s paintings. He later reminisced: “Lorca was the greatest friendship of my life and my most fundamental experience. He felt an intense physical love for me, not platonic. I would have liked to reciprocate it but I was unable to. It was a tragic love due to the fact that we could not share it.”

Perhaps, Dalí’s greatest tragedy was not being able to fully correspond to Lorca’s affection during the happy years at the Students’ Residence where a photo of them holding hands was taken. Who knows what would have happened if, instead of Gala, Dalí had dared to live openly with Lorca but, that, as they say, is another story.

Ignacio Darnaude, an art scholar, lecturer, and film producer, is currently developing the docuseries Hiding in Plain Sight: Breaking the Queer Code in Art

Muy bien hecho Sr. Garcia.

I heartily recommend the above article about Federico Lorca and Salvador Dali.I read the article before in the print issue of The G&L Review.I just knew Salvador Dali was an abstract painter,but I didn’t know about his gay past.Glad that Weho Online was able to reprint the article,so many thanks for the opportunity for local readers to see this.

What an eye-opening and beautiful article. I love Dali’s surrealist paintings and I have read most of Garcia Lorca’s gorgeous work. This article made me understand and appreciate them even more. I didn’t know about their doomed love affair, what a revelation. It should be turned into a movie!.