“The most effective way to destroy people is to deny and obliterate their own understanding of their history.” — George Orwell

Have you ever heard the term “excusable homicide”? Neither had I. A scary term, isn’t it, particularly for any vilified and persecuted minority? In 1969, that term was found in the California Penal Code.

In April 1969, just two months prior to the Stonewall Rebellion, “excusable homicide” was the term used in a ruling by the Los Angeles Coroner’s office after a handcuffed, gay man had been “beat, kicked, and stomped” to death by the LAPD’s Vice Squad at the Dover Hotel. That deadly violence has a present day resonance, doesn’t it?

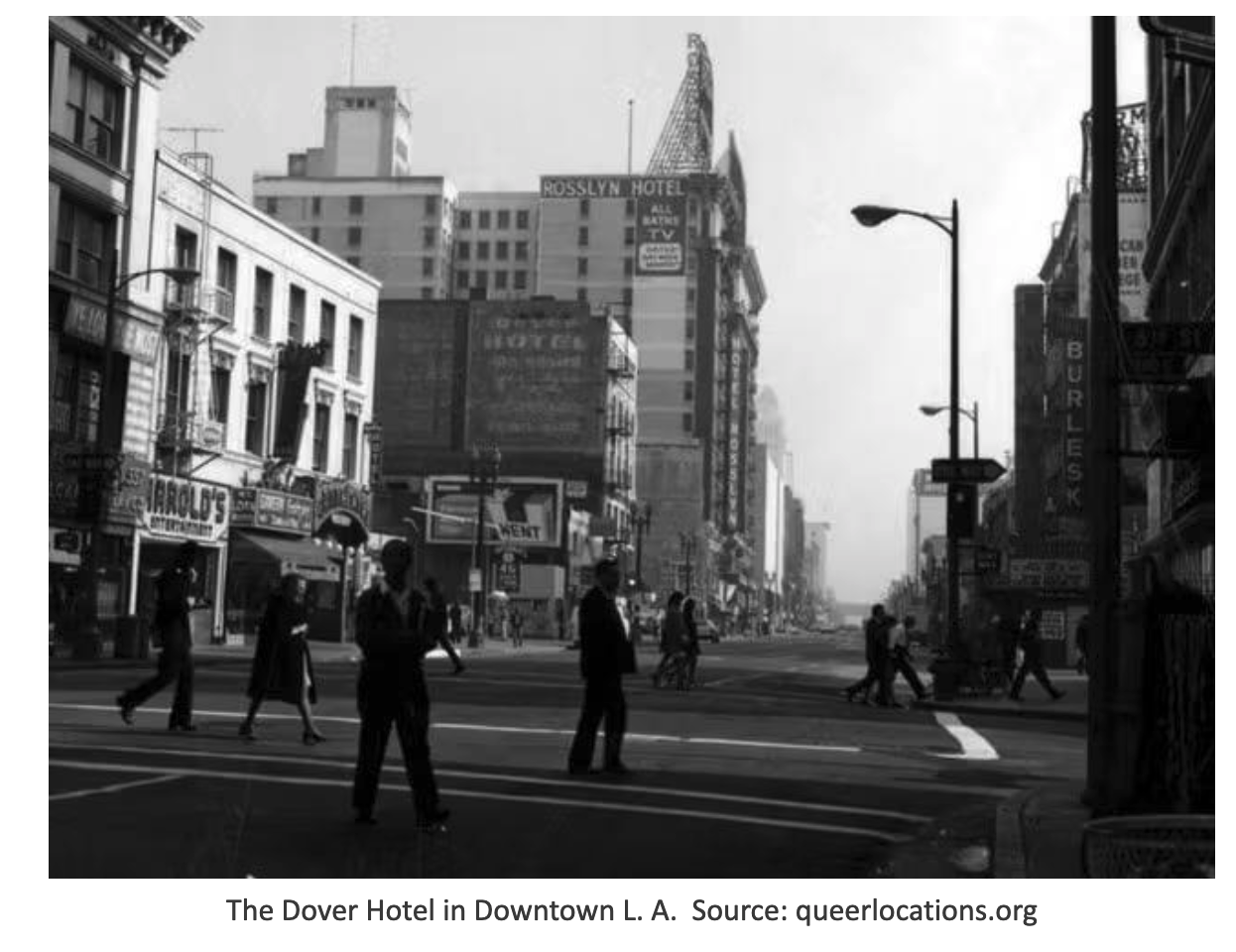

By 1969, the Dover Hotel located at 525 S. Main Street in downtown Los Angeles had become a gathering place for ordinary gay men due to its inexpensive rates and close proximity to the few pioneering gay bars on S. Main St. and the cruising in Pershing Square at night, a scene memorably described by John Rechy in the classic gay novel City Of Night.

Shortly after midnight on March 9, 1969, a loud ruckus was heard on the second floor of the Dover Hotel, causing guests on the third floor

to race down to the second floor to investigate. They witnessed a 37- year-old, handcuffed, gay man, being severely pummelled—kicked and stomped— by five men who identified themselves as LAPD officers. His name was Howard Efland (he registered as J. McCann, an alias), a married man who frequented the gay friendly hotel weekly. Those who knew Efland described him as “quiet” and “timid.” He was dragged to a police car. Witnesses reported that Efland screamed out as he was kicked into the back seat of the police vehicle, “Help me! My God—someone help me!”

At 2 a.m., a half hour after the LAPD hurried Efland away from the Dover, a nearby hospital declared him dead.

Howard Efland’s fate was replicated innumerable times in cities, towns, and rural areas across the United States after World War II, an especially virulent and deadly time for the ideology and practice of systemic hetero supremacy. During the war, younger gay men found each other on the battlefield and in rest and recuperation situations, and after the war they did not want to go back to the small towns and small minds of the U.S. they had come from—places that were soul deadening to closeted gay men.

A significant demographic relocation of gay men happened in the post-war period. These ex-GIs congregated in large cities along the East and West coasts of the U.S. with their clandestine gay bars and secretly expanding gay friendship networks. In the process, gay men became much more prevalent and easier targets for hetero supremacist violence in the vicinity of places like Pershing Square, West Lake Park (now MacArthur Park), and the Echo Park lake area in L.A. after dark—places like the Dover Hotel.

Unless a gay murder victim was white, rich, and famous, gay homicides were rarely mentioned or cared about by newspapers or other media. Civil rights organizations were totally disinterested in such cases and appalled at the suggestion that they get involved. Police departments refused to investigate such cases and their own culpability, and civic officials couldn’t care less. The only good fag was a dead fag.

This time, in early 1969 in L.A., however, there was a significant difference. A historic pivot point had been reached. At this juncture, a short historical detour is required which will connect with Efland’s murder in a critical way.

The Los Angeles Advocate Shines a Crucial Light on the Murder

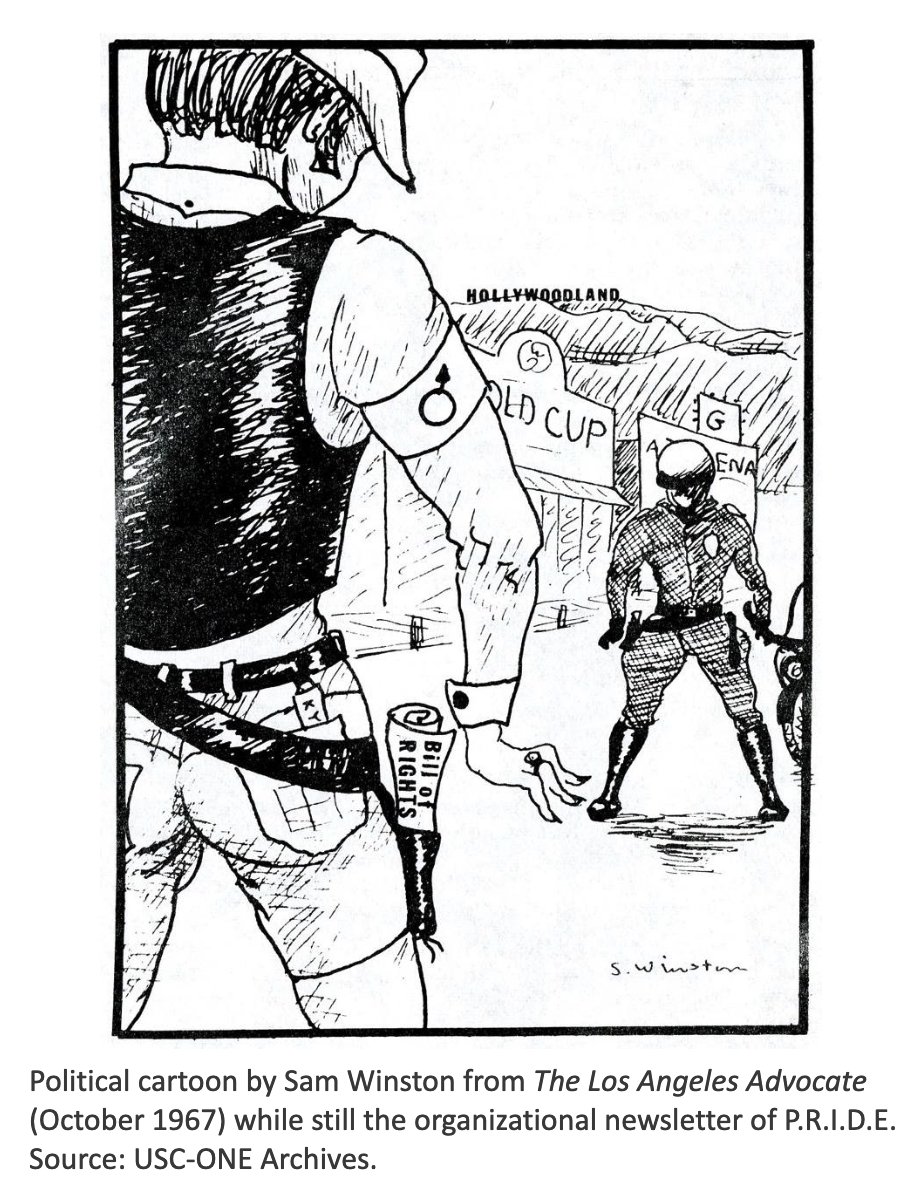

Los Angeles is often described as “the cradle of gay history in the United States.” Very importantly, in 1967, L.A. was also the birthplace of American gay journalism with the appearance of The Los Angeles Advocate, the first gay newspaper in the U.S. The Los Angeles Advocate was founded by its publisher, Dick Michaels (a pseudonym for Richard Mitch), and his companion, Bill Rand (Bill Rau), and called itself “the newspaper of the homophile community.” It grew out of the newsletter of the short-lived, proto-Gay Liberation organization Personal Rights In Defense and Education in L.A. (P.R.I.D.E., 1966-1968), a membership organization that collapsed in March 1968 and whose roots stemmed from the Society for Individual Rights (SIR), a conservative, homophile organization founded in San Francisco in 1964.

[The term “homophile,” whose usage started in L.A. and spread elsewhere in the U.S., is used in this article to refer to the period between 1953-1969. Homophile organizations can be characterized as conservative, assimilationist, law reformist, hetero imitative, “don’t rock the boat,” and emancipationist (“please accept us”). Today, since about 1985, the gay community in L.A., and elsewhere, has been in a neo-homophile period with elite capture. See my essays “Understanding Los Angeles Gay History” and “Elite Capture in the LGBTQ Community in Los Angeles (And Everywhere Else).”]

From its founding in 1967 as a monthly publication, The Los Angeles Advocate primarily covered news and other features about gays in L.A. and California; late in 1969 it became a national publication that came out every two weeks. Although coverage was still largely focused on L.A., where its core readership was located, the publication removed “Los Angeles” from its name. While actual circulation data about alternative newspapers is elusive, it is speculated, perhaps on the high side, that in the late 1960s The Los Angeles Advocate probably printed 4000 copies monthly with 4-5 people reading each copy; in the early 1970s, after going national, The Advocate claimed a print run of 20,000. At the Hoover St. Commune (1971-73), each issue was probably read by 20 gay men.

The Advocate’s founding publisher, Michaels, was a 1960s-type conservative, entrepreneurial Republican with a core of personal integrity. Initially, he was opposed to Gay Liberation’s revolutionary methods. After Stonewall, however, through dialogues with Morris Kight and me, in a 1972 editorial Michaels finally endorsed what the Gay Liberation movement was doing in L.A.

Michaels was outraged by Efland’s murder, and in April and May of 1969, The Los Angeles Advocate’s front-page coverage of the case informed its readers directly and from the scene of action for the first time of the LAPD’s violence that most gay men heard about previously only secondarily through hearsay about gay bar raids. The Los Angeles Advocate played the same important role as such newspapers fulfilled in other minority communities—reporting what the dominant culture refused to report.

The L.A. Coroner’s Sham Hearing

The Los Angeles Advocate kept a gay spotlight on the Efland case by insisting on public accountability instead of the customary manner of disposing of gay murder cases, silently and mysteriously, out of public sight or knowledge. At first, Efland’s body couldn’t be located because no one knew his real name. Through The Advocate’s insistence, the corpse was finally located, the lacerations on Efland’s kicked and stomped body serving as evidence.

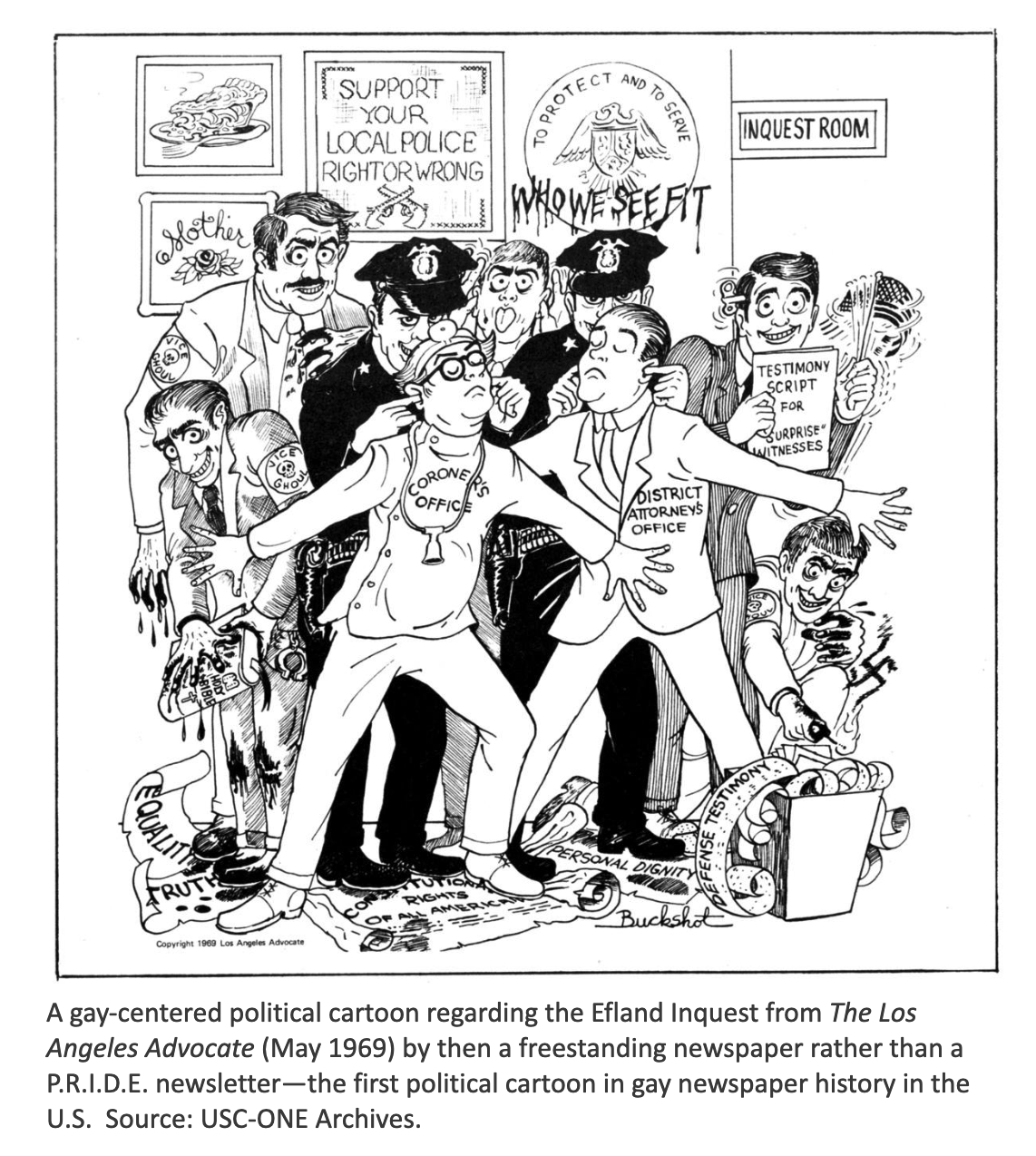

On April 4, 1969, a Coroner’s inquest was convened to investigate the cause of Efland’s death in police custody. The Los Angeles Advocate had spread word of the inquest and all 50 seats in the hearing room were filled by witnesses to the murder and advocates of justice for Efland, probably all gay men and their allies. The inquest consisted of a seven-man jury; only the head of the inquest and an L.A. Assistant District Attorney were allowed to ask questions. It was reported that the D.A. acted like a defense attorney for the police, asking questions that were skewed in the direction of exonerating the LAPD. The testimony of the men who witnessed the whole scene at the Dover was disregarded.

The five police officers claimed that Efland had been arrested on lewd conduct charges involving another gay man, a Mr. Garcia, in room 220, and he violently resisted arrest, leading to his injuries. We will never know what actually happened that night. The sex with Garcia that the police alleged to have witnessed was a lie. Garcia had not even registered yet at the hotel at the time of the arrest. The inquest jury absolved the LAPD of any responsibility for Efland’s death—”excusable homicide”—and officially ruled that his death was due to a massive hemorrhage caused by a ruptured pancreas. The LAPD told Efland’s parents he died of a heart attack.

L.A. Coroner’s declaring the murder an “excusable homicide” was an outrage. Its subtext conveyed the message that there was societal disregard for the LAPD murder of gay men. As the inquest ended, it was reported that several men, presumably gay men, stood up and shouted, “This must stop! This senseless persecution must stop.”

The LAPD‘s Garcia Accusation Hoax

On March 9, 1969, at 4 a.m., three hours after the LAPD took Efland away, the LAPD came back to the Dover Hotel and unlocked the door of room 220, where they found Garcia asleep in his bed. They arrested him for lewd conduct, claiming they had witnessed him having sex with Efland three hours previously. This makes no sense whatsoever. If the police had actually witnessed such a sex scene both would have been arrested immediately. Moreover, there was concrete evidence that Garcia had not yet registered at the hotel at the time Efland had been taken away. In police fashion, they also claimed they found two bags of “bennies” (slang for an amphetamine called Benzedrine) in Garcia’s room, which Garcia denied ever having seen.

On May 10, 1969, a court trial regarding Garcia’s arrest for lewd conduct was held, lasting 30 minutes. The arresting officer did not show up in court, usually a sign that the LAPD would have been embarrassed there because their lies had been uncovered and the Defense Attorney would have had the right to cross examine the police officer. After reading a transcript of the police officer’s testimony, the presiding judge exclaimed, “The officer’s testimony seems quite bizarre,” and he quickly dismissed the case.

Importance of Efland’s Murder to Gay History in Los Angeles And Elsewhere

The Efland case is important for three historical reasons.

First, it clearly brought into the light for the first time how the LAPD managed the scenario regarding violence toward gay men, heretofore, invisible in police orchestrated public darkness and without accountability or consequences. Even though gay men at the time reached out to newspapers, television, radio, civil rights organizations, even the ACLU, regarding the Efland murder, none showed any interest in the case. Only The Advocate shed some light.

That total lack of interest reminded me of early 1970, several months after the Efland murder, when I reached out to the progressive National Lawyers Guild office in Hollywood seeking help in L.A. GLF’s effort to combat LAPD police bar raids, arrests, and violence. Without explanation, I was told that the Guild’s assistance was not possible, and I was quickly ushered out. In the early 1970s, hetero supremacy also suffused the New Left, as it had done previously with the Old Left. As GLFs became more visible and influential, that hetero obduracy slowly changed, helped along by the Black Panthers. In August 1970, Huey Newton, leader of the Black Panthers, recognized Women’s Liberation and Gay Liberation as fellow “revolutionary brothers and sisters” in equal standing with other liberation movements at the time.

Second, The Advocate reporting, a mere tiny tip, but a pioneering, important tiny tip, of a gigantic hidden iceberg of hetero supremacist violence, began the process of revealing LAPD brutality toward gay men and awakening gay understanding of their pervasive oppression in society in a way that could not be excused or tolerated.

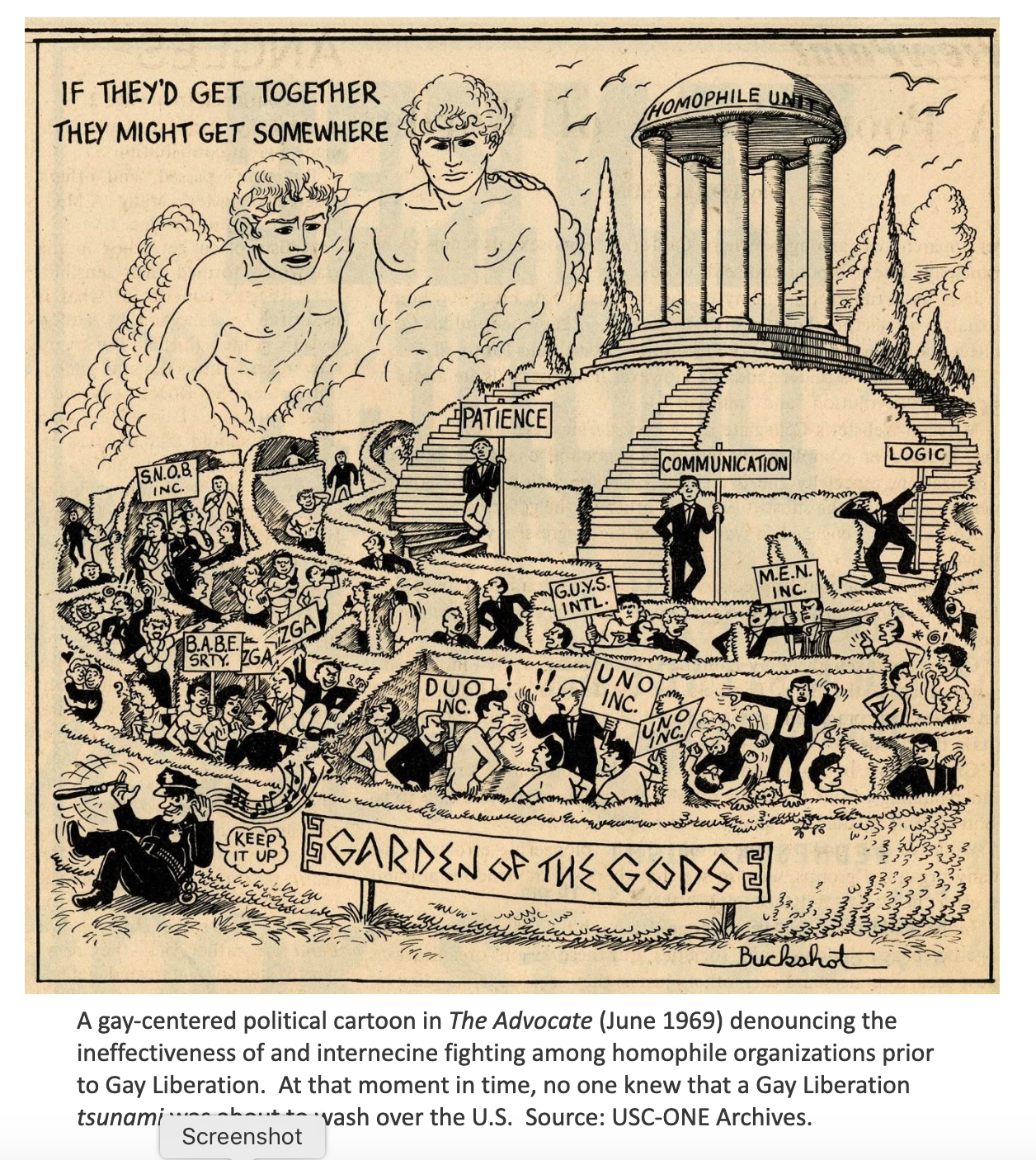

In June 1969, Michaels published a scathing, front-page editorial regarding the Efland murder, calling out a society that gave the police such unlimited power, denouncing homophile organizations for being ineffective and engaged in internecine warfare, and criticizing so-called “responsible” gay men who condescendingly looked down at “irresponsible” gay men like Efland and others that indirectly brought race and class into the picture. The Advocate continued playing a rapidly increasing role on a national level, and, because the newspaper primarily covered Gay Liberation in Los Angeles after Stonewall, it gave L.A. GLF and its innovative, successful model of gay community organizing an outsized role nationally as well.

In the historiography of liberation and decolonization movements,

a differentiation is often made between “secondary resistance” to oppression (educating people about their oppression) and “primary resistance” to oppression (directly confronting the oppressor). Using that revolutionary paradigm in Los Angeles, the pioneering Mattachine (1950-53), the Homophile effort (1953-1969), and the early The Los Angeles Advocate can be viewed as secondary resistance (education) and the non-violent Gay Liberation movement (1969-1985) as primary resistance (direct confrontation) to hetero supremacy—a liberation movement whose radical, grassroots, militant methods resulted in the liberation of LGBTQ people and began the difficult journey toward authentic freedom.

And third, the Efland murder provides an understanding of the historical field onto which the L.A. Gay Liberation Front and GLFs elsewhere were born a few months after Efland’s murder, a liberation movement replacing a moribund homophile effort. As a result of that militant Stonewall consciousness, never again would gay men stand by idly, cover their eyes, or run away in fear of arrest or even their lives.

This liberation process is what Frantz Fanon in The Wretched of the Earth called a “collective awakening” – a non-violent social revolution by means of direct action and mass civil disobedience.

By late 1969, a new, younger Gay Liberation generation, initially small but relentless, inspired and energized by the social revolutions occurring around them by other oppressed peoples, actively, directly, and decisively fought back for the first time. GLF was successful in L.A. and elsewhere. But as LGBTQ empowerment lives on, so does a wounded hetero supremacy, and something wounded can be very dangerous. The historical lesson of the Weimar Republic in Germany (1918-1933) must never be forgotten by LGBTQ people—one year dancing freely in Berlin and the next year in Nazi concentration camps.

Also, may the memory of Howard Efland be not forgotten, nor the memory of all those other gay men murdered, burned alive at the stake, and individually and communally traumatized over time by hetero supremacists—brutally, lethally, and continuously—for at least a thousand years in the Western world.

The Advocate’s Michaels will be given the last word, just as he ended his previously mentioned accusatory editorial in June 1969 (the month/year of Stonewall): “In the final analysis, it’s up to us. We can give McCann’s (Efland) death as much or as little meaning as we like. So far, it had none.”

* * *

Don Kilhefner, Ph.D., a Gay Liberation pioneer, has also been a gay community organizer in Los Angeles and nationally for over 55 years,

including cofounding the L.A. LGBT Center, Van Ness Recovery House,

and the international Radical Faeries movement.

Don Kilhefner cofounded the L.A. Gay and Lesbian Community Services Center (GLCSC) when it was on Highland Avenue just north of Santa Monica Boulevard. Somehow, when the Center moved to Hollywood it became the Lesbian and Gay, etc. Center. Not even in alphabetical order and, as I recall, neither Don Kilhefner nor Morris Kight were in favor of this. The Center ignored the founders. Then the transition to LGBT Center which states on their web site that they are the largest LGBTQ+ organization in the world. Back in the day, there was one inclusive word for us and that was… Read more »

Thank you for keeping this story alive after so many decades. The history of gay liberation in the U.S. in my mind was more important in L.A. than other cities. As important as Stonewall was, the demonstrations protesting police brutality at Silverlake’s Black Cat Tavern preceded Stonewall by two years (see Wikipedia).