This story by Bob Bishop originally ran in 2016. It has been updated for clarity and timeliness.

The commercialized, family-friendly, city-sponsored event we know as WeHo Pride traces its origins back more than 50 years to the radical parade of the first LA Pride.

Pride celebrations all over the world commemorate one of the most important events in LGBTQ history, the 1969 rebellion at the Stonewall Inn, a gay bar on Christopher Street in New York.

When West Hollywood became a city in 1984, it became the epicenter of pride festivities. But the road was far from smooth at that point.

Trouble emerged right out of the gate when West Hollywood’s Valerie Terrigno – the first openly gay mayor of a U.S. city – began serving a 60-day sentence in May 1986 for embezzling public funds from a counseling center where she was director. When West Hollywood was incorporated in November 1984, Terrigno was elected to the city council and chosen as its first mayor by her elected cohorts.

At least she spared the organizers of the Gay Pride Parade an uncomfortable decision by opting not to ride in a restaurant-sponsored parade vehicle the following month. A vice president of CSW said the group had hoped Terrigno would not force the issue, but noted the parade organizer was prepared to block her appearance. “There’s no way she would go down that parade route,” he said, adding: “She would disgrace herself if she tried.”

A headline in the Los Angeles Times from June 1986 summarized the city’s embarrassment succinctly: “When West Hollywood’s First Mayor Was Driven from City Hall, She Took Part of the Dream of a ‘Gay Camelot’ with Her.”

For times like that in LA Pride’s history, a blog maintained by the Los Angeles Public Library provides much needed perspective. Under the headline “Pride in the Face of Adversity: How the Herald Examiner Covered the LGBT Community in Los Angeles,” Senior Librarian Christina Rice wrote: “As a mainstream news outlet in the 20th Century, it’s probably not surprising that the Los Angeles Herald Express (later Herald Examiner) newspaper gave little coverage to the LGBT community. The Herald’s image archive, now maintained at the Los Angeles Public Library, seemingly reflected the newspaper’s attitude towards the city’s LGBT residents which in turn was more than likely a reflection of popular views at the time.

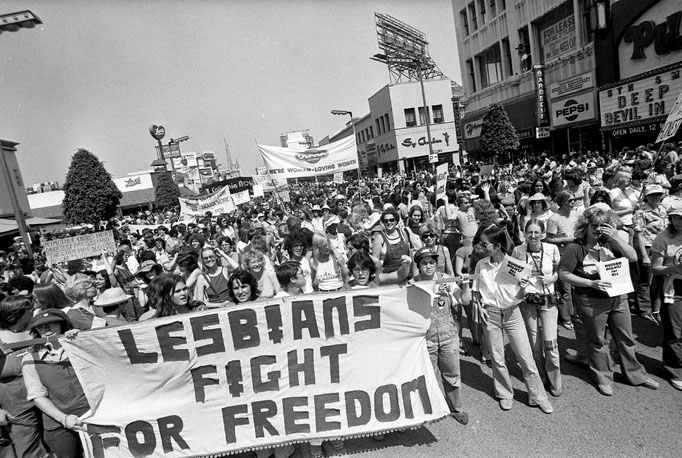

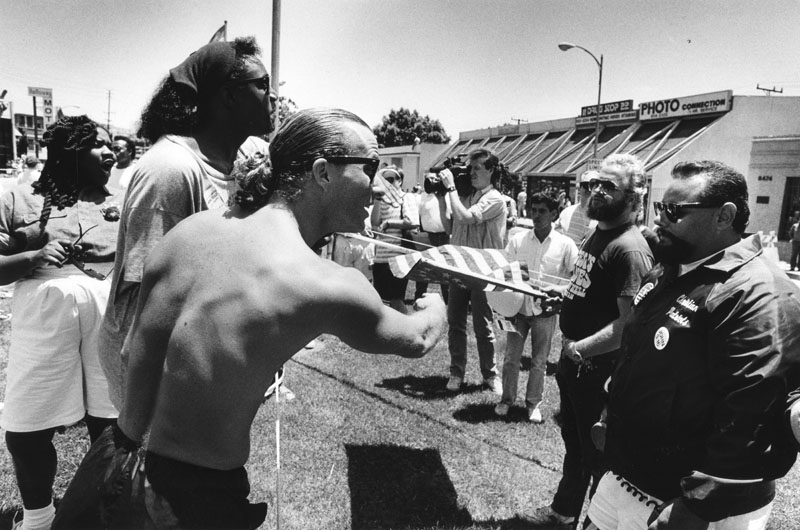

“Photos relating to the LGBT community are almost non-existent in the Herald collection prior to the 1970s. The few that have turned up focus exclusively on men being held in jail after having been arrested for ‘masquerading’ in women’s clothing with terms like ‘fairies’ written on the back of the photos in grease pencil. As public activism increased in the 1970s and 1980s, so did stories relating to issues and events. However, handwritten derogatory comments continued to appear on backs of photos and negative envelopes depicting Gay Pride parades, AIDS awareness, and other fights for equal rights.”

“What’s striking about the LGBT photos in the Herald collection is that in the face of constant adversity during the decades, the people depicted in them universally display pride, confidence, and a sense of self, whether they’re behind bars, marching in a parade, or in court fight for marriage equality.”

In the Beginning

The world’s first actual gay pride parade that commemorated the Stonewall riots a year earlier in New York city rolled along Hollywood Boulevard in June 28, 1970, attended by some 50,000 onlookers. The procession was officially sanctioned by the City of Los Angeles, but not without CSW founders duking it out with a homophobic L.A. Police Department (LAPD) to secure a parade permit. New York and other cities held unofficial “marches” but L.A. was the first city to have a police-approved event with a parade permit along with police protection.

Parade organizers were led by the Rev. Troy Perry, founder of the Universal Fellowship of Metropolitan Community Churches; Morris Kight, founder of the Gay Liberation Front and Reverend Bob Humphries, founder of the United States Mission, a gay welfare organization.

According to first-hand accounts of the first appearance before the L.A. Police Commission, Police Chief Ed Davis began by asking, “Did you know homosexuality is illegal in the State of California?” After a short debate over the issue, the chief made his position even more clear. “Well, I want to tell you something. As far as I’m concerned, granting a parade permit to a group of homosexuals to parade down Hollywood Boulevard would be the same as giving a permit to a group of thieves and robbers.”

A commission member added, “There’ll be violence in the streets.” The commission decided to grant a parade permit but only if the gays could post two bonds, one for $1 million and another for $500,000. A minimum requirement of 3,000 people marching in the parade was imposed, or else the parade would have to proceed on sidewalks.

Thanks to the help of the American Civil Liberties Union, all conditions were dropped, except for a requirement to pay $1,500 for police protection. Even that requirement was voided by the California Supreme Court, which forced the LAPD to provide the gay parade the same protection at no cost as it did all other similar marches.

Rev. Perry estimated some 50,000 people watched the parade from Hollywood’s sidewalks – a tremendous beginning. The 1970 parade’s success immediately led to talk of making it an annual event. Entries the next two years caused controversies, and disagreements within the steering committee led to no parade being held in 1973. It continued annually after that on Hollywood Boulevard through 1978, but CSW moved it to West Hollywood in 1979 because of skirmishes between gay activists and the LAPD, as well as steadily increasing crowds.

How Many Homosexuals Does It Take to Have a Parade?

In addition to controversies, another staple of LA Pride has been widely varying estimates of crowd size. Parade organizers believed an accurate headcount was derived by tripling whatever “official” figure was provided by LAPD or the L.A. County Sheriff’s Department.

In 1985, for example, news media reported the West Hollywood parade “drew between 50,000 and 150,000 well-mannered spectators.” The smaller crowd estimate came from a sheriff’s spokesman based upon surveillance by a deputy from a helicopter; the larger from event organizers, who said the sheriff’s figure was “not believable.” Nobody argued that over the 80,000 people were said to have attended the festival that year.

By any measure, the parade was a huge success and grew substantially every year. By 1989, the official crowd size was placed at more than 200,000, with some 10,000 in the parade itself along with 257 floats and contingents.

The crowd size rose to about 300,000 spectators in 1990 with some 300 groups in the parade. An additional 60,000 people attended the parade the following year, according to press reports, reaching a whopping 400,000 for 1995’s parade.

You’re Out – Like It or Not

The parade consistently has shown a knack for ginning up juicy and sometimes worthwhile political news. Politicians generally avoided the parade in the early years, but made up for it as soon as LA Pride began to resemble an episode of “South Park.” All of a sudden, it was cool to be gay, or at least, to be seen with gays and lesbians.

The most notable incident came in 1991 when parade organizers outed Los Angeles County Tax Assessor Kenneth Hahn. “A surprise awaited County Assessor Kenneth P. Hahn as he took his place Sunday with other politicians participating in West Hollywood’s annual Gay and Lesbian Pride Parade,” the Los Angeles Times said in an article published June 25, 1991. “As the dignitaries were introduced to the crowd, Hahn was ‘kind of flabbergasted’ to hear himself described as ‘senior-most elected openly gay official in Los Angeles.’

“Hahn, elected (in 1990) after a long career in the assessor’s office, said Monday that he has never denied his homosexuality when asked about it, and has been identified in the gay press and even the Washington Post as a gay politician. Nonetheless, he had never made a public pronouncement of his sexual preference, and he said Monday that he did not know that parade officials intended to do so for him.

“’I thought I would be treated like any other elected official,’” Hahn, 51, said in an interview. ‘My sexual orientation has nothing to do with my job … I’ve never been a gay candidate, just a candidate who happened to be gay’.”

David Smith, spokesman for the Gay and Lesbian Community Center, a parade sponsor, said Hahn’s homosexuality was noted in the introduction because it fit with the parade’s Gay Pride theme (“Together in Pride”).

The Hahn incident came at a time when “outing” – the effort by some gays to expose the homosexuality of celebrities, politicians and business leaders – was dividing the gay community. But 1991 was notable for a much bigger reason. For the first time, the LAPD permitted uniformed gay officers to set up a recruitment booth among the AIDS awareness booths and disco tent. No LAPD officers marched in the parade.

Gay activists claimed that many years of pressuring LAPD over anti-gay attitudes and policies of former police chiefs Ed Davis and Darryl Gates were paying off. The gay officers staffing the recruitment booth said they were essentially “pulling back the curtains” on a secret society within Southern California law enforcement.

“One by one and step by step, Los Angeles’ homosexual lawmen and law women are publicly disclosing their private lifestyles,” the news media noted. “In doing so, they stirred controversy among colleagues, incited some hostility from elements of the public and won praise from gay activists.”

Regardless of the year, LA Pride was absolutely essential in bringing the LGBT community together to support major thrusts like securing increased funding for AIDS research and medical care, human rights domestic partnerships and the right to marry. Anti-gay legislation was a persistent focus year-in and year-out, particularly the veto by Gov. Pete Wilson of AB101, a civil rights bill that would have barred California employers and landlords from discriminating against people on the basis of sexual orientation.

Grand – and Maybe One or Two Not-So-Grand – Marshals

Long-time parade-goers are still talking about 2005 and the selection of the heterosexual daughter-mother team of “celebutante” Paris Hilton and reality TV star Kathy Hilton as co-grand marshals of the parade. The big question back then was “Why?”

The heiress starred in Fox’s reality TV show “The Simple Life,” while her mother starred in an NBC reality program, “I Want to be a Hilton.” The theme of the parade and festival that year was “How Do You Wear Your Pride?” if that helps any.

“The first thing that pops into my mind is, are there no gay people that could possibly grand marshal our own parade?” questioned Advocate.com columnist Charles Karel Bouley II

.

Former CSW president Rodney Scott pointed out that in years past the parade had featured other heterosexual grand marshals who were popular within the gay community, including 1980s rocker Cyndi Lauper (2003), actress Jennifer Tilly (2004) and comedian Kathy Griffin (2006).

“Kathy and Paris were brought forward by members of our community,” he said. “Here’s a mother and daughter that want to lend their voices to issues – like gay marriage, adoption and hate crimes – that face our community. Their response was very enthusiastic – and appropriately stunned that they would be included.” Besides, he noted, Paris lived in West Hollywood.

Other grand marshal choices needed no explanation, including San Francisco Supervisor Harvey Milk (1978); actress Martha Raye (1982); actress Patty Duke (1986); psychologist Dr. Evelyn Hooker (1986); U.S. Rep. Maxine Waters (1989); Elvira, Mistress of the Dark (1990); actors Dick Sargeant and Elizabeth Montgomery (1992); Judith Light (1995); former NBA player John Amacchi (2007); Sharon and Kelly Osbourne (2010); figure skating champion Johnny Weir (2011); and actress Molly Ringwald (2012).

Same Thing Only Different

The Hiltons were brought in because the festival and parade were losing their magic with locals, who were calling the overall celebration “pretty lame,” “predictable” and “dull.” Such comments prompted West Hollywood city officials to get involved. Their goal was to beef up the event, although the game plan had nothing to do with burly guys in tight leather shorts (for once).

The City Council convened a special task force made up of marketing and financial experts as well as gay rights advocates to study the parade. The group’s analysis: Pride needed more of a head transplant than a mere facial makeover, so it suggested organizers and the city needed to both liven up and expand the gay pride celebration.

Instead of only a weekend event, the panel of experts recommended a month-long series of arts, film, cultural and social activities that celebrate the creativity of not only West Hollywood, but all of Los Angeles.

Further, panel members suggested putting professionals in charge of marketing and promoting “Pride Month,” with the city itself coordinating the renewed festival.

One other thing: the group emphasized there should be “higher standards for participation in the parade.” Obviously, not all recommendations made the cut, but it may be helpful to see how officials attempted to reengineer the celebration once before.

More views of LA Prides past are on the following pages:

Maybe it would make sense to have two grand marshalls. One being a celebrity hetero ally/friend of the community, and the other one being an lgbt activist.