EDITOR’S NOTE: The is another in a series of occasional stories titled “The Grownups” about West Hollywood residents 75 years old or older who are active in civic life.

She’s been called one of the 100 most influential LGBT people in America. Her work has had an impact on the LGBT rights movement in countless ways, everything from fighting anti-LGBT ballot initiatives and AIDS to improving police sensitivity about LGBT issues and even starting a housing organization for aging gays and lesbians.

At 91, Ivy Bottini is one of those aging lesbians, but she’s not slowing down. Her eyes may not be working perfectly and her knees are not holding up as well as they once did, but she’s still forging on.

She’s still busy with her activism – she just helped get the California statute of limitations for rape and sexual assault removed. She’s still busy with her paintings – she just had an art show in Paso Robles. She’s still busy as a performance artist – she’s working on a new one-woman show. But she’s also taking time to reflect on her 91 years – she just finished working on a memoir about her life and activism.

Few can claim all the accomplishments that Ivy Bottini can. Although she’s been in the spotlight often in the past 50 years, she doesn’t especially crave the limelight. She just sees things that need to be done, underdogs that need a champion, and dives in.

“Ivy is a starter,” explains her longtime girlfriend Dottie Wine. “She has no ego investment in what she does. She probably at some level wants credit where credit is due, but she has no ego investment in terms of ‘this is my project and it will go my way.’ She finds a cause she believes in, she gets it going, she gathers other people who maybe have different skill sets than she does, maybe more energy than she has and then she either becomes an advisor or she bows out and it goes on and has a life of its own.”

Bottini finds activism exciting, exhilarating and fulfilling.

“Activism is the only way to fly,” Bottini says. “It’s very satisfying because you actually have a chance to fight back against unacceptable things. You not only get work done, you can change minds because they can see you. I believe in feet on the street to get the fight done.”

Born a Fighter

Bottini’s father, Archie Gaffney, had been a boxer and taught her the sport from an early age, telling her, “you’re a girl and you’re going to have to defend yourself.” Since she was an only child, Bottini’s father treated her like the son he did not have.

“My father taught me to box, gave me a BB gun and took me fishing,” she recalls. “All these things you normally associate a father doing with a son, my father did with me. I loved it. I was very appreciative. I had a wonderful childhood with my father.”

Growing up in Malverne on Long Island in New York, Bottini was a tomboy. In fact, she was the leader of the neighborhood gang.

“I was the ruler of the gang on my street,” she recalls. “They were all boys on my street, except for me and one other girl, who was interested in make-up and hair, so she didn’t join in with us.”

She knew she was attracted to women, but accepted a marriage proposal from Eddie Bottini nonetheless because that is what society expected. Shortly before the wedding in January 1952, she went to a psychiatrist to talk about her attraction to women. He advised her to ‘cleave’ to her husband and her married friends.

The couple had two children, Laura and Lisa. Although most women in the 1950s were housewives, Bottini had a full-time job as an art director for Newsday, where she worked from 1955-1971. Thus, she was already rebelling against the conventional norms, even before she became an activist.

National Organization for Women

In the 1960s as the women’s movement was getting underway, Bottini joined the National Organization for Women (NOW) and became the president of the New York City chapter.

“It was the first organization that cared about women,” she recalls. “It focused on women and their issues; not kids, not guys, but women.”

As part of her NOW job, Bottini used a then-new technique called “consciousness raising,” holding workshops where feminist issues and the way society treated women were discussed.

“I felt passionate to spread the feminist consciousness raising because it so changed women’s lives,” she says. “The groups I lead were political in nature. They lasted eight weeks with the goal of creating new activists at the end of it.”

When New York City NOW held a press conference in 1968, Bottini inadvertently came out on TV while answering a question. “I said, ‘As a lesbian, I think . . .,’” she recounts. “I didn’t even realize I’d said it at first. But the rest of the room did.”

Once publicly out, she pushed to include lesbian rights in the women’s movement, an idea that was not well received by Betty Friedan, who wrote “The Feminine Mystique” and was considered the mother of NOW.

Bottini soon found herself voted out of office, losing by just seven votes. She says it was part of a larger effort, orchestrated by Friedan, to expunge lesbians from NOW.

“They wanted to keep lesbianism out of feminism,” recalls Bottini, who also designed the logo that NOW still uses today. “And there were a lot of closeted lesbians in NOW.”

Being kicked out of NOW was a crushing blow. By this point, Bottini and her husband had divorced, so she decided to start her life fresh and moved to California with her girlfriend. Upon arrival in Los Angeles, she learned a state NOW conference was underway, so she dropped by. When she walked into the conference hall, the attendees gave her a huge round of applause.

While that applause was terribly satisfying, the incidents surrounding her ouster from NOW are still some of the most painful in her life. She reports that even today, national NOW officials still maintain there was no larger plan to expel her, that she was merely voted out of office.

But in March 2016, some 45 years after being ousted, she was honored for her activism at a ceremony sponsored by the Hollywood chapter of NOW. During that ceremony, Hollywood NOW and the California state NOW presented her with a letter apologizing for the way she was treated.

“I was dumbfounded,” Bottini recalls. “I was totally caught off guard. I didn’t know anything about it. I could expect it from Hollywood NOW. But state NOW, California? The whole state? They had to vote on that. All the California chapters, they had to vote on that. It was fabulous that someone in NOW finally acknowledged that I was forced out, that the vote was a set up.”

That letter is now one of her most cherished possessions. She keeps the letter framed on a table in her West Hollywood condominium on Kings Road and happily shows it to her guests.

Falling in Love

In 1974, Bottini developed Grave’s Disease, a thyroid condition, and moved back to New York so her mother could take care of her. After she got better, she intended to stay in New York, but fate intervened.

While attending a NOW conference in San Francisco in April 1975, she was a facilitator for a consciousness raising workshop titled, “Is Lesbianism a part of Feminism?” During that workshop, a voluptuous 30-year-old in a green dress came in late and immediately captured Bottini’s heart.

“We were doing introductions, and I said, ‘I’m by experience heterosexual only, but I’m open,’” recalls Dottie Wine, the 30-year-old in the green dress. “Ivy had already spotted me, and she decided to check out whether that was a true statement and the rest is history.”

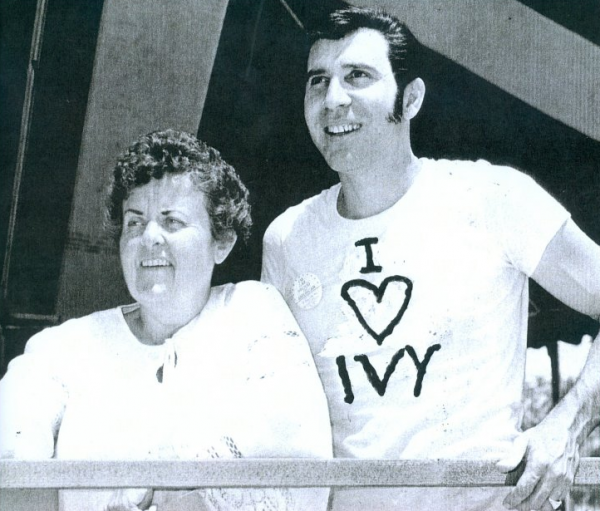

Bottini says she was instantly smitten. “I saw [Dottie] and it was all over for me,” recalls Bottini. “She was just stunning. Still is.”

Madly in love, Bottini returned to California and the two moved in together. In the ensuing 42 years, they have had an on-again-off-again relationship, although mostly on. Even during the periods when they’re not together, they have remained close friends.

“There’s always a push-pull with Ivy,” Wine observes. “We’re both stubborn, strong-willed women. When we can let each other be who we are and find some way to compatibly spend time, it works. And when we can’t, it doesn’t.”

LGBT Rights

By the time she and Wine moved in together, Bottini had started a career as a performance artist. She was represented by the Williams Brothers (of which singer Andy Williams was a part) and performing a one-woman show, “The Faces of Women.” She and Wine traveled all across the country doing shows.

Fate intervened once again to bring her firmly into the LGBT rights movement. She was hired as a grassroots organizer to help defeat the Brigg’s Initiative, the 1978 ballot initiative that would have banned lesbians and gays from teaching school. Her organizing also helped defeat Lyndon LaRouche’s 1986 ballot initiative to quarantine people with AIDS.

Her grassroots efforts continued when the Los Angeles Police Department seemed especially insensitive to LGBT issues, and she started the Los Angeles Lesbian/Gay Police Advisory Board. The many projects she worked on included launching Gay & Lesbian Elder Housing, which built Triangle Square, the affordable housing complex for gay and lesbian senior citizens in Hollywood.

In 1999, Bottini joined the city of West Hollywood’s Lesbian and Gay Advisory Board (LGAB), a position she held for 16 years, ten of them as the board chair.

She particularly enjoyed LGAB because it had funding to get programs initiated and also the power of West Hollywood City Hall behind it.

“I liked being on LGAB because the city could supply resources,” she says. “We could come up with an idea and the city could make a program out of it, put it into the budget. So there were advantages to doing it that way. All of this stuff you could get done through the council.”

Fighting AIDS

In 1982, her longtime friend, Ken Schnorr, collapsed and was hospitalized with this mysterious new disease affecting gay men. Bottini telephoned the Centers for Disease Control trying to get answers, but the CDC was unable to help her, and Schnorr died a few weeks later.

Angry, she started researching what little information about the disease that there was at that point. She founded the AIDS Network LA, an early clearing house for disease information. Later she helped co-found AIDS Project LA. She also held some of the very first forums for gay men about this strange disease.

During those forums, she advised men to stop what they were doing sexually, saying that was what was killing them. Bottini believed AIDS (which at that point was called GRID – Gay Related Immune Deficiency) was transmitted via body fluids, long before there was medical consensus about transmission.

LGBT documentary filmmaker Glenne McElhinney included Bottini in her acclaimed 2011 film, “On These Shoulders We Stand,” which tells the story of a dozen Los Angeles area gay men and lesbians and the battles they had to fight in the 1940s-70s.

McElhinney recalls having dinner at Basix with Bottini to discuss including her in the film. When they arrived, several people applauded Bottini. Then, while Bottini was in the restroom, a man came over and told her about those forums Bottini held in 1982.

“He said to me, ‘Ivy Bottini saved my life’,” McElhinney said. “A few weeks later, we were again at dinner and once again, while she was in the restroom, another man came up and told me almost the exact same story, saying, ‘Ivy Bottini saved my life. All my friends are dead and I’m still alive because I listened to what she was saying’.”

Strong Leader

LGBT activist Sue Sexton met Bottini is 1995 when she answered an ad for a room to rent in Bottini’s Craftsman house on Coronado Terrace in Silver Lake/Echo Park. She considers Bottini a mentor, noting that it was Bottini who encouraged her to apply to become a member of LGAB.

Sexton believes one of the things that makes Bottini a good leader is her ability to see the bigger picture.

“Ivy has a clarity to see a clear path for what is the best thing for the community,” Sexton says. “Her great passion has always been for the larger community. She just always could see ahead down the road. One thing that always impressed me was how she had that ability to see where to go.”

Bottini’s friend Judith Branzburg agrees about Bottini’s clarity and ability to see the big picture.

“Ivy has tremendous political foresight,” Branzburg says. “She could tell what was going to happen and then she would organize to deal with it. She gets people organized.”

Another leadership quality that Sexton has observed is the fact Bottini doesn’t hold grudges.

“Ivy always did things for the greater good, but didn’t take things personally,” Sexton says. “For the most part, she could disagree with someone, but still respect them and work with them again.”

Indeed, Bottini notes that she and LA-based LGBT activist Morris Kight had a huge falling out in the early 1980s about how to deal with the emerging AIDS crisis.

“Morris and I didn’t speak for three years, but I always loved him,” Bottini says.

Similarly, even though she was ousted from NOW, Bottini continued to work with the organization periodically on workshops and conferences because she believed in the feminist cause.

Bottini even has a small degree of compassion toward her nemesis, Betty Friedan, saying, “I have such mixed emotions about her [Friedan]. She pisses me off really strongly, but at the same time, I really admire her.”

Anti-Assimilation

As much as Bottini has fought for LBGT rights, she has advocated against LGBT assimilation. She doesn’t believe it is necessary for LGBT culture, sensibilities and history to get swallowed up (and consequently lost) as mainstream America becomes more accepting of gays.

She feels that assimilation is imposing hetero-normative ideas onto the LGBT community. She believes the gay community should be creating its own norms and celebrating its uniqueness rather than contorting itself to match traditional heterosexual standards.

That’s why she’s long been opposed to same sex-marriage. Oh, she’s not opposed to a loving, same-sex couple being together in a long-term, committed relationship. However, she is against same-sex couples feeling like they have to fall into the traditional male and female roles and everything else that the word ‘marriage’ implies.

“I wish we could still call it ‘domestic partnership,’” Bottini says. “‘Marriage’ comes with too many ‘shoulds’ – you should do this, you have to do that, you must do this. Just the name ‘marriage’ comes with incredible baggage – ownership, duties and roles. Just the name affects your brain. If they could have called it something else, anything but ‘marriage.’ But the people who wanted ‘marriage’ really want all of that that comes with it.”

Along the same lines, one of the first programs she worked on when she joined LGAB was an awareness campaign about domestic violence among same-sex couples. However, she opted to call it “partner abuse.”

“I just felt that gay men and lesbians, especially gay men, would not respond to the term ‘domestic violence,’ it was too heterosexual,” Bottini recalls. “So, I called it ‘partner abuse.’ That I knew they’d understand.”

Not Pushy, but Determined

Over the years Bottini has attracted a fair number of critics, who frequently call her “pushy.” Bottini responds by saying, “I don’t consider myself pushy. I consider myself determined.”

That determined attitude and unconventional way of thinking is something that her friend Marian Jones admires.

“Ivy just stands up to it all that she feels is not going on the right path or is not good for the community or the people or the women or whatever,” Jones says. “She just doesn’t take a lot of crap and I have a lot of respect for that.”

Jones met Bottini 32 years ago in an acting class for gays and lesbians and quickly hit it off with her. Later, when Jones started a theatre company to produce original works by lesbian playwrights, she named it the Ivy Theater.

“Ivy gave voice to people who didn’t always have a voice [through her activism], says Jones, “and the Ivy Theater was about telling stories that you never hear that people live.”

Still Doing Art

When she’s not busy being an activist, Bottini spends her time as an artist. However, painting has become more difficult in the last ten years due to her macular degeneration. She still has peripheral vision, but has little center vision. Yet even with failing eyesight, she still manages to paint daily.

“I don’t know how I do it. I can picture in my mind what I want to paint. I know where the lines should be and what the shapes should be,” says Bottini, who studied graphic design at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn. “I don’t watch my hands while I paint, I look at the canvas and somehow it gets done.”

Dottie Wine admires the fact Bottini has adapted to the failing eyesight but is still determined to paint.

“As her eyes have changed, her art has also changed, but she still manages to paint amazing works,” she says. “Ivy is an extremely adaptable survivor of circumstances. She’s a great role model for ‘keep on keeping on’ despite what challenges life delivers.”

Wine notes that when Bottini is busy on an activist cause, she puts the art aside. When she needs to retreat from activism, that’s when she resumes the artwork.

“She can put her creativity on the canvas or in the streets, not both at the same time,” Wine observes.

Sharing Her Story

With all that she has accomplished, it’s no surprise that Bottini has written a memoir with the help of her friend Judith Branzburg, a retired English professor at Pasadena City College.

Bottini recorded many hours of tapes about her life and Branzburg crafted those stories into a 250-page memoir, tentatively titled “The Liberation of Ivy Bottini: A Memoir of Love and Activism.” Branzburg is currently submitting the book to potential publishers.

“Her story was really amazing, she kept persisting,” Branzburg says. “She became a feminist activist, then a lesbian activist, then a gay activist. She dedicated her life to making life better for women and for gays and lesbians.”

Bottini’s life story is also the subject of a new play, “InclusIVitY: The Ivy Bottini Story,” by playwright Al Schnupp, a professor of theater at California Polytechnic State University in San Luis Obispo. “InclusIVitY,” which had its world premiere in August in Paso Robles, is written in rhyming couplets and features 18 songs about her life.

“Ivy’s story makes for great drama,” says Schnupp, who hopes to one day transform the play into an opera. “Her love of life, her humor, her gutsiness, her hutzpah, the fact she is fighting for justice, inclusivity, fighting Propositions 6 and 64, all make for a great story. She’s Saint Joan in my eyes.”

As for the future, Bottini has no bucket list. She’s taking things as they come.

She’s fighting against overdevelopment in West Hollywood, disturbed that gentrification is gradually pushing the city further away from the gay and lesbian utopia it once promised to be.

She’s also working on her new one-woman show and, of course, still doing her painting. “I’m going to work in my studio and create beauty instead of anger,” she says.

There is only one Ivy Bottini and we are lucky to have her as part of our community. Ivy is still on the forefront fighting for a better Pride and for LGBT rights.

Ivy Bottini is a class act.