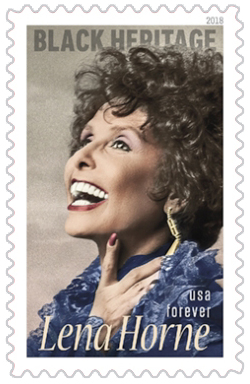

In celebration of February’s Black History Month, the U.S. Postal Service has issued a stamp honoring singer, actress, civil-rights activist and former West Hollywood resident Lena Horne.

One of just a handful of major acts discovered on the Sunset Strip, Lena Horne is the first former West Hollywood resident to receive this honor. (Hattie McDaniel, honoree in 2006, was a long-time Los Angeles resident, and Ella Fitzgerald, honored in 2007, also performed on the Strip.)

Best remembered for her live concerts in top venues like Lincoln Center and Carnegie Hall in New York and the old Cocoanut Grove in Los Angeles, Horne Horne’s forte was show tunes and jazz standards. Her signature song was “Stormy Weather.”

But it was in the movies that she made her mark. Under contract with MGM in the 1940s, she appeared in groundbreaking roles in a series of musicals, including “Panama Hattie,” “Cabin in the Sky” and “Swing Fever.”

Her big break – the break that made that MGM contract possible – came in 1942, when she was 25 years old and living on Horn Avenue in West Hollywood. In January, just six weeks after the bombing at Pearl Harbor, she made her debut before a packed audience of Hollywood A-listers and studio executives at Little Troc, a nightclub on the Sunset Strip.

A New York Times columnist later described the indelible impression Horne made that night, recalling that she stepped from darkness into a single soft spotlight, and then, without introduction, launched into “The Man I Love,” followed by “Stormy Weather” and six more standards. After her set, “The crowd got chestnut happy,” the columnist wrote. “They whistled for more.” Within weeks, an MGM exec who had been in the audience that night had signed Horne to a long-term contract.

***

Lena Mary Calhoun Horne was born on June 30, 1917, in Brooklyn. Her ancestors were descendants of the family of John C. Calhoun, a U.S. senator from South Carolina who also served as vice president under President John Quincy Adams. Because of this pedigree, Horne’s forebears had received educations and enjoyed other privileges not available to most non-whites in that era.

She began her career as a dancer at Harlem’s Cotton Club and later toured the country as the featured vocalist with jazz orchestras. Deeply disturbed by the racism she encountered on the road, Horne returned to New York and played the nightclub circuit. In early 1941 Sunset Strip impresario Felix Young caught her show at Café Society in Greenwich Village. He hired her on the spot to be his opening act at Little Troc.

After Horne’s sold-out run at Little Troc ended in April 1942, she moved down the Strip to Mocambo, where, according to a Los Angeles Daily News columnist, she caused such a sensation that “Hollywood protocol was turned on its head. Cops were called in to hold back crowds made up of screen stars – on one night a friend of mine counted 62 big names in a mob of several hundred niftily habilimented people – who had tried futilely to get in the Mocambo to see and hear Horne.”

But even as she basked in this sudden success Horne found herself confronted by Jim Crow, Hollywood style. At a party at Cole Porter’s house, Greta Garbo swooned over her, but Miriam Hopkins, a native of Savannah, took Horne aside and asked her why she was “not like all the other [blacks]” who were restricted from socializing with whites.

In movies with mostly white casts, scenes in which Horne appeared were filmed separately so that theatre owners in the South could cut them out. In the movie “Words and Music,” for example, Horne’s rendition of “The Lady Is a Tramp” was edited out in Southern theatres. “They would just snip it out,” Horne’s daughter, the writer Gail Buckley Lumet, recalled recently. “Take scissors and snip snip when it got south of the Mason-Dixon Line. She could never be in anything that furthered the plot or was a crucial moment in the movie.”

Horne was even confronted by Jim Crow at her home in West Hollywood. “A few neighbors objected so strenuously to the presence of an African-American family in their midst that they circulated a petition to force them out,” Lumet wrote in her memoir, “The Hornes: An American Family.” It was quickly quashed by Humphrey Bogart and his wife, Mayo Methot, who lived at the corner of Horn and Shoreham, and their friend, Peter Lorre, who lived a few doors down from Horne’s house.

Horne was even confronted by Jim Crow at her home in West Hollywood. “A few neighbors objected so strenuously to the presence of an African-American family in their midst that they circulated a petition to force them out,” Lumet wrote in her memoir, “The Hornes: An American Family.” It was quickly quashed by Humphrey Bogart and his wife, Mayo Methot, who lived at the corner of Horn and Shoreham, and their friend, Peter Lorre, who lived a few doors down from Horne’s house.

Another episode revealed the absurdity of Hollywood racism. When MGM was casting the musical “Showboat,” Horne was considered a shoo-in for the role of Julie La Verne, a mixed race singer. But because the role was integral to the story, Julie’s scenes could not be excised for Southern moviegoers. The part was given instead to Horne’s friend Ava Gardner, whose singing had to be dubbed.

There were good times, too. After work, Horne often dropped by Café Gala, the gay-friendly nightclub across the street from her house – in the former Spago building on Horn that has been vacant now for decades – where she would sing for the after-hours crowds. During a break between films, she was booked at Café Gala as the headliner. “There were lines of customers down the Strip,” Gail Lumet wrote, “and café regulars, including Tyrone Power and his wife Annabella, were furious because they could not get in.”

As her clout grew in the 1940s, Horne began suing restaurants and theaters that refused service to black people. In the 1950s, after she joined a civil rights group, she was blacklisted in Hollywood. In the 1960s, she toured the country on behalf of the NAACP and took part in the March on Washington led by Dr. Martin Luther King.

Over the course of her long career, Lena Horne won three Grammys and a Tony for her one-woman show, “Lena Horne: The Lady and Her Music.” She also received the NAACP Spingarn Medal and the Actors Equity Paul Robeson Award. She was a Kennedy Center Honors recipient in 1984, and is included in the International Civil Rights Walk of Fame at the Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Site.

Lena Horne died of heart failure on May 9, 2010, in New York City. She was 93.