Founded on rent control rabble-rousing, West Hollywood has earned a reputation for political and social activism that’s raging as fiercely as ever. This year alone has seen loud protests over (1) City Councilmember John Duran’s public comments about the latest round of sexual misbehavior allegations against him, (2) another drug overdose at the home of Democrat Party donor Ed Buck, and (3) union organizing attempts at the Andaz Hotel.

Needless to say, the city’s residents firmly believe that everybody has a right to his or her opinions on subjects large and small. Here’s a photo summary of the city’s long history of “community engagement” covering a variety of protests, some significant and others less so, all before the year 2000 for historical perspective.

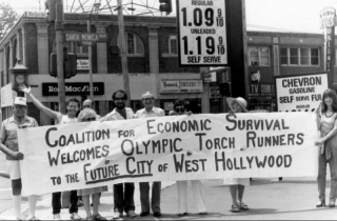

Cityhood and Rent Control

Several times between 1957 and 1966, various factions in the West Hollywood community had tried – but failed – to incorporate the area into a city, mainly to keep it from being annexed by Los Angeles. That’s what made the successful cityhood effort in 1984 so remarkable.

The driving force this time was the pending expiration of Los Angeles County’s rent control law in 1985. Estimates in the late 1970s calculated that 85 to 90% of the West Hollywood area’s residents were renters. A coalition of young leftist activists, gays, a loyal army of elderly Jewish tenants and Russian immigrants all shared a concern for renter’s rights.

Under the auspices of the Coalition for Economic Survival, they successfully pushed for cityhood. West Hollywood officially incorporated as a city in November 1984; the City Council enacted the Rent Stabilization ordinance on June 27, 1985, to maintain affordable rental housing.

‘There’s Something Happening Here’ – The Sunset Strip Hippie Riots

at Pandora’s Box to fight for their right to party, also known as a protest against a 10 p.m. curfew. (Herald Examiner

Collection, Los Angeles Public Library

The Sunset Strip scene was more grit than glamour by the mid-1960s. The former hangout for Hollywood’s elite was dominated by hippies and partying teenagers. Their drinking, doing drugs and interfering with traffic led authorities to impose a strict 10 p.m. curfew, which rock music fans saw as an infringement on their civil rights.

Tensions between police and the counterculture crowd were at a peak when more than 1,000 people gathered Nov. 12, 1966 for a vigil at Pandora’s Box, an underage nightclub at the corner of Sunset and Crescent Heights boulevards scheduled for demolition. The crowd – including Jack Nicholson, Peter Fonda, Sonny and Cher – erupted in protest against perceived repressive enforcement of recently invoked curfew laws.

The unrest continued the next night and off and on throughout November and December. In this light, Bob Gibson, manager of the Byrds and the Mamas and the Papas reflected, “If you had to put your finger on an event that was a barometer of the tide turning, it would probably be the Sunset Strip riots.”

The curfew riots characterized the anti-Vietnam War protests of following years, inspiring Stephen Stills of Buffalo Springfield to write the song “For What It’s Worth (Stop, children, what’s that sound?),” which became one of the defining songs of the era’s anti-war protests.

West Hollywood commemorated the riots’ 50th anniversary with a brochure available online.

Artists against the Vietnam War

The Peace Tower, a six-story artistic protest against the Vietnam War, was built in 1966 at the corner of La Cienega and Sunset boulevards by the Artists Protest Committee. It featured hundreds of paintings sent by artists from around the world.

The group also staged a “White Out” on Gallery Row along La Cienega on the border of West Hollywood in which participating artists and dealers covered work in white paper. Los Angeles police intervened when activists began posting signs on parking meters and lamp posts.

Another organization, the “Angry Arts” of Southern California, also took up the mantle of protesting the Vietnam War. Its creative protest activities that took place in June and July of 1967 included poetry readings, film screenings, theatrical performances, and a sale of some of the paintings that had been on display at the Peace Tower.

Electric Streetcar Strikes

West Hollywood’s place in electric streetcar history is

secured by the rail yard at Santa Monica and San Vicente boulevards built by

Moses Sherman and Eli Clark in 1897. Today it’s home to the Metropolitan

Transportation Authority’s Division 7 bus yard.

The site became part of Pacific Electric, whose management

was vehemently anti-union. Operators and conductors would strike repeatedly

during the first half of the 20th century, the most violent challenge to the

company’s open-shop policies coming in 1919 when operators were joined in

solidarity by track-layers. Owner Henry Huntington hired replacement workers

and used city police to break-up groups of protesting employees.

A rare look inside Pacific Electric’s West Hollywood car barn where streetcars damaged by striking workers were repaired. (Photo courtesy of Pacific Electric Historical Society)

A riot broke out in downtown Los Angeles, streetcar wheels were greased, and some cars were even overturned. The result was a pay increase for workers, but the company remained an open shop. This meant periodic strikes continued, particularly during the 1940s. Pacific Electric also faced strikes in 1901, 1903, 1910, 1934 and 1943, according to LAcurbed.com.

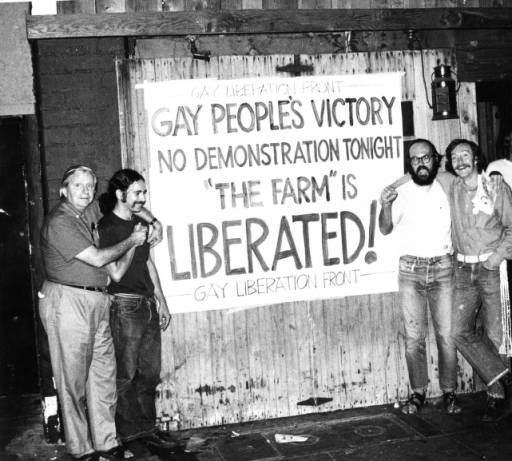

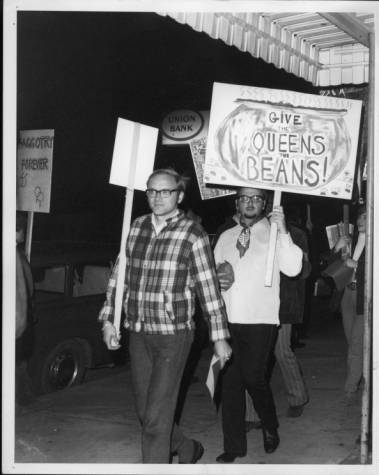

Liberating Bars & Restaurants

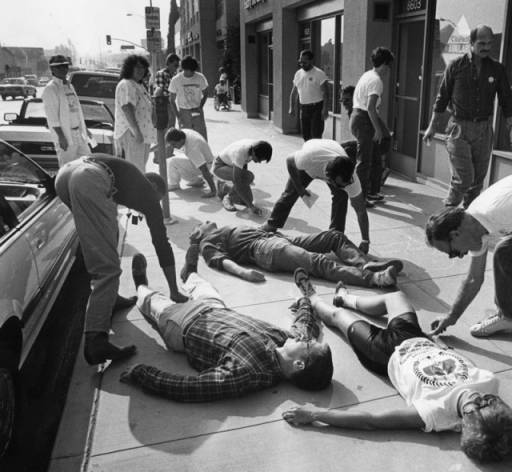

AIDS Demonstrations

Numerous demonstrations in the fight against HIV/AIDS took place along Santa Monica Boulevard, where markers tell much of the story today. Bronze plaques, part of the West Hollywood Memorial Walk, are engraved with the names of those who have died from the disease, for example.

At the intersection with Crescent Heights Boulevard is the Matthew Shepard Human Rights Triangle. That’s where Wayne Karr and Lou Lance, both HIV-positive, held a hunger strike in 1989 demanding the public release of an experimental AIDS drug.

In 1991, in support of AB 101, the California gay civil rights bill, Rob Roberts fasted on there. When Gov. Pete Wilson vetoed the bill, non-violent protests were held nightly on the site for two weeks.

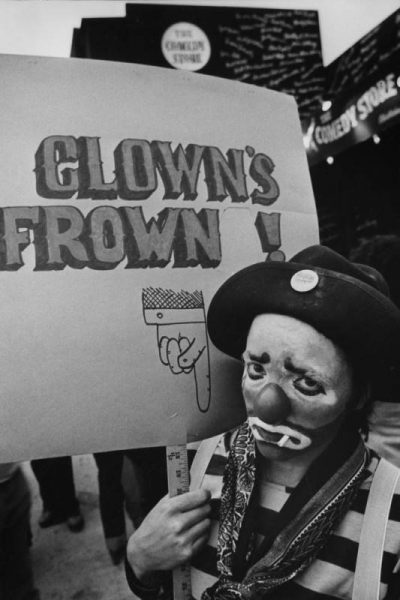

Sad Clown at a Happy Place

Comics who regularly played the Comedy Store on the Sunset Strip organized a six-week strike in 1979 because they weren’t getting paid. The owner, Mitzi Shore, considered the club a “showcase” room, an opportune place for comics to develop their acts and get discovered.

It worked well for many comics. Guys like David Letterman and Jay Leno, already flush with their first successes, picketed alongside their less well-known colleagues, according to comedyhistory101.com.

A handful of comics crossed the picket lines, simultaneously earning the owner’s enduring affection and the barbed scorn of their fellow comics. When the strike was settled, comics benefitted from a payment scheme whereby they would get 50% of the door in the Main Room or $25 a set in the smaller Original Room. Some bad vibes certainly endured, but for most of the comics, there seemed to be palpable relief that the strike was over.

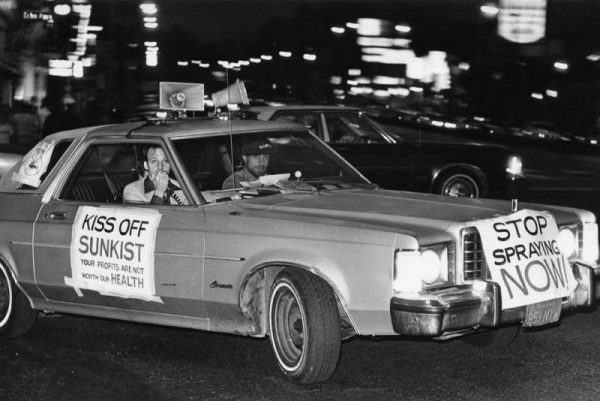

Medfly Mayhem

to protest state-ordered aerial spraying of the chemical malathion over Los Angeles to combat an infestation of the Mediterranean Fruit Fly (medfly). (Photograph by James Ruebsamen, Herald Examiner Collection, Los Angeles Public Library)

Now these guys have the right idea. Why walk during a protest when you can ride?

Very few insects have caused the widespread panic, political controversy, and public outcry like the Mediterranean fruit fly (medfly) shortly after it appeared in California in the early 1980s.

Considered one of the world’s most disruptive agricultural pests, the medfly threatened the state’s agricultural Industry, with its high cash crops such as citrus and stone fruit.

Gov. Jerry Brown ordered aerial spraying of the chemical malathion to nip medfly infestations in the bud, leading to unprecedented uprisings by residents, who said the spraying, with helicopters flying low over their homes, was disturbing. They were also concerned that malathion may be harmful to their health.

When a single medfly was found in 1980, a year of debate about how to deal with the pest followed. By the time Gov. Brown ordered aerial spraying, the infestation was huge. The delay is blamed for costing the farm industry $100 million, as well as Brown’s loss to Pete Wilson in the 1982 Senate race.

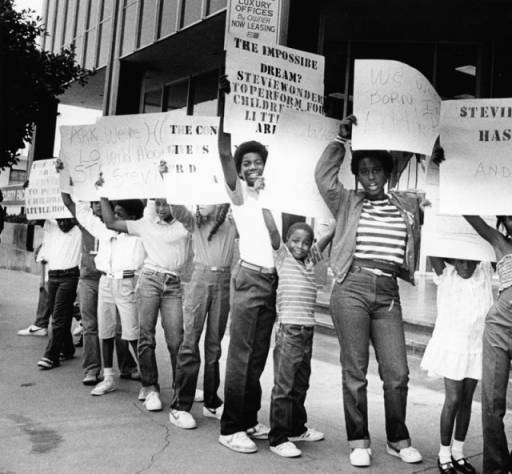

Hoping to See Stevie Wonder

(Photo by Mike Mullen, Herald Examiner Collection, Los Angeles Public Library)

This group of 13 kids from Little Rock, Ark., staged a protest outside the Sunset Strip office of Stevie Wonder’s manager on Aug. 26, 1982. They hoped to see Wonder in person to ask him to perform in Arkansas for a fundraiser.

A check of his concert dates shows that he never made it to Arkansas, but the kids still got a vacation in Hollywood from their efforts. Too bad Wonder didn’t see them … or maybe he did, if you believe the conspiracy theory that says he really isn’t blind.

ACT UP/Los Angeles is not only one of the most important activist groups in the history of West Hollywood but also Los Angeles and the state of California. As a member of ACT UP/LA since 1988 I am disappointed that Bishop failed to include ACT UP/LA in this otherwise excellent survey. ACT UP/LA met in Plummer Park for ten years, 1987-1997. During that time numerous protests, political funerals, and other public events were organized and led by ACT UP/LA. The impact of ACT UP/LA has been documented in a book by Benita Roth and journalists Karen Ocamb, David Reid and… Read more »

this piece is wonderful. thank you. when people ask me “why west hollywood?’……THIS IS WHY.