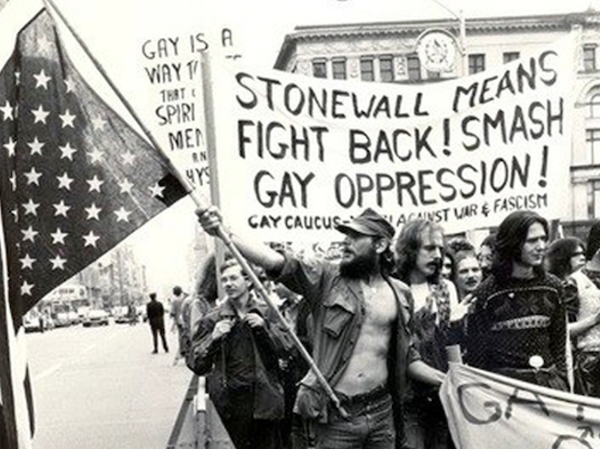

Here we are, 50 years to the day from that night in New York when 100+ gay men and women said, “no more,” and stood up to the police who raided the Stonewall Inn. As a point of historical fact, there had been riots at gay bars before. Here in Los Angeles, the Black Cat riots had taken place two years earlier. But it took the riots at Stonewall to galvanize the entire LGBTQ community and to shock the nation into paying attention to our plight.

Paying attention didn’t mean immediate social or legal acceptance, though. It wasn’t until 1973 that the American Psychiatric Association removed homosexuality from the list of mental illnesses. And our community’s journey toward greater civil rights has been a brutal one.

In 1980, the first gay man died of AIDS in the United States. Ken Horne was the first of many—too many.

It was about that time when my personal journey as an out gay man began.

Before I became a lawyer, before I even contemplated going to law school, I wanted to work in U.S. embassies overseas. I didn’t especially care what I did there, as long as I had the opportunity to represent the American government in foreign countries.

So in 1984, I took the Foreign Service exam – a two-day ordeal that involved written materials and oral role-playing scenarios – and I actually passed the exam. I eagerly waited to be called to the diplomatic corps. And I waited, and I waited. But no call came.

After deciding I couldn’t keep waiting, I moved on to consider other ways to work with the government, and, answering an ad I had seen in the newspaper, I scheduled an interview with the CIA. The interview went surprisingly well. I hit it off with the interviewer and answered all the questions with ease. At the end of the interview, though, the CIA agent asked me a question that surprised me: “Have you ever slept with another man?” I knew that being gay was a problem for security services back then, but I didn’t think they’d be so blatant about it in the interview process. When I answered “Yes,” the man followed up with, “Do you think it could happen again?”

I replied, “I sure hope so.”

Needless to say, I didn’t get the job. And I never heard from the Foreign Service either.

Realizing that my future career lay in the private sector, I turned to a more traditional path: I went to law school, summered with prestigious firms, and ended up as an associate in the Los Angeles office of one of the largest law firms in the country. During all of this time, I didn’t hide the fact that I was gay. I brought my partner to firm events and made sure people knew he was not just my buddy. The law firms surprised me by not seeming to care, so I started out in my legal career thinking, this is going to work out just fine.

But being gay did have a big effect on my career. Although I was well-respected, partners would choose other lawyers for high-profile cases, lawyers who fit in better with the firm culture and who were more “presentable” to clients. Most of the time, this was done unconsciously but the result was still the same: I needed to work twice as hard to get ahead, and I had to struggle to keep my career on track.

As I struggled to fit in as a gay first-year associate at a big law firm, the gay community was facing a much more serious struggle. The AIDS crisis had reached epidemic proportions. It was the AIDS crisis, more than any other event, that brought home to me just how much society, and the US government in particular, treated the LGBTQ population as expendable and without rights.

By the time President Ronald Reagan first uttered the word “AIDS” in 1986, over 20,000 Americans had died from the disease. His refusal to fund AIDS research by the Center for Disease Control allowed the disease to go unchecked. By 1989, when he left office, over 70,000 people were dead from AIDS.

It wasn’t just Reagan who didn’t care about the lives of gay men. When one of my good friends, who was suffering from AIDS in Los Angeles, called one night to say he needed help, my partner and I went to his apartment and found him lying in a pool of blood and feces, close to death. We called 911, but when the fire department paramedics arrived, they took a look at my friend, realized that this was an AIDS victim, and refused to give him treatment or to transport him. They simply left us there to deal with the situation on our own. We managed to get a private ambulance to transport him, luckily as it turns out, because we learned that he would have died of blood loss if he had been denied medical treatment for much longer.

In 1991, the AIDS crisis struck even closer to home for me. I learned that my brother had come down with the disease. This was a time when there was still no medication that could save an AIDS victim’s life. I flew back to New York every month to visit my brother in the hospital, and during that first year in my law firm when partners tested new associates, determining which ones had the character and fortitude to make it as a lawyer, my brother contracted disease after disease that his compromised immune system couldn’t fight off. Eventually, I got a call while I was at my firm’s first-year lawyers’ retreat that I needed to get to my brother’s side right away. His death was not peaceful, and almost 30 years later his ordeal still haunts me. Steve was 33 when he died.

In 2008, I married my partner on our 25th anniversary (which in any other context would be a very odd thing to say). We could do that because for a brief window of time, same-sex marriage was deemed legal in California. It wouldn’t be legal nationally until 2015. I never thought I would see same-sex marriage legalized, let alone be treated as an ordinary occurrence. The fact that it occurred 46 years after the Stonewall Riot puts that victory in perspective.

The response of the LGBTQ community to all the challenges we’ve faced—police harassment, anti-gay legislation, the AIDS crisis, the fight for marriage equality—has impressed me enormously. In the years after Stonewall, we as a group came together and created a political force that was and continues to be so much greater than our numbers would imply. Organizations like ACT UP performed in-your-face acts of civil disobedience, political groups like the Human Rights Campaign Fund tapped into pent-up anger and showed how much money LGBTQ groups were able and willing to spend on political causes, and people in all parts of the country began coming out the closet in numbers never seen before.

Even with these advancements, we are again facing an attempt to stigmatize, dehumanize and strip civil rights from the LGBTQ population. There are renewed attempts to put us back in the closet, to tell us that we are less than equal. But I am an optimist, and I have seen the tide of history over the past 50 years sweep away bigoted, uninformed and hateful points of view. I have seen our community stand up and roar, and I have seen how a simple act like coming out can transform the way a whole community views civil rights. Because of the bravery of a handful of drag queens and others at the Stonewall Inn 50 years ago, I have been able to forge a successful career as a gay lawyer in a major law firm, to get married and to lead a deeply fulfilling life. So when people ask me if I think that all our advancements will survive and that we will continue to press the march of civil rights forward, I think I have reason to answer with the same optimistic answer I have always given: I sure hope so.

Ditto to what LADoug wrote. Karl, thank you for sharing your experiences and your optimism – your story.

Ken – a deep article, thank you for sharing your journey and gay history.

A full-hearted tribute to those who have passed due to AIDS, hate, or suicide.

50 years of progress, thank -you to all of the gay/queer advocates who have paved the way for all of us.

I’d like to see our community return to it’s grass roots. I was fortunate to know those brave men and women of that era. Courageous and pioneers. If it weren’t for them, I’d be killed or forced to live in silence. Keeping historical information alive , is the key to ensuring nothing like this happens again. We must be unified and inclusive of all people. This fight still continues.

Thank you for a very personally powerful and poignant essay and asking the most important question gay people can be asking of ourselves these days. I respectfully inquire what are your suggestions as an answer to the question in this regard? I bow in your direction.

What we need is a world class LGBT museum to honor our past, enrich our present, and help create our future. West Hollywood, with its vibrant LGBT tourism and access to Hollywood would be a perfect location for such a venue.

Agreed