EDITOR’S NOTE: On March 16, data from the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health showed that West Hollywood had the highest rate of COVID-19 infections of any of the 335 cities and communities in Los Angeles County. The number of confirmed infections in WeHo on that day was five. On March 22, both West Hollywood and Brentwood were reported to have 18 confirmed infections, putting them both at the top of the list of most highly infected communities. But as of Monday, Brentwood ranked No. 118 on the list of infections per number of residents and West Hollywood, with 133 infections, ranked No. 20. Crosstown LA, a data-driven, non-profit news organization, has taken a look at why those and other affluent communities in Los Angeles County are sliding down the list of infections as a percentage of population.

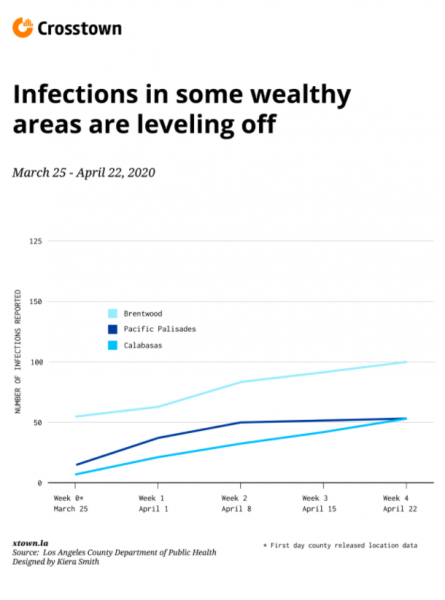

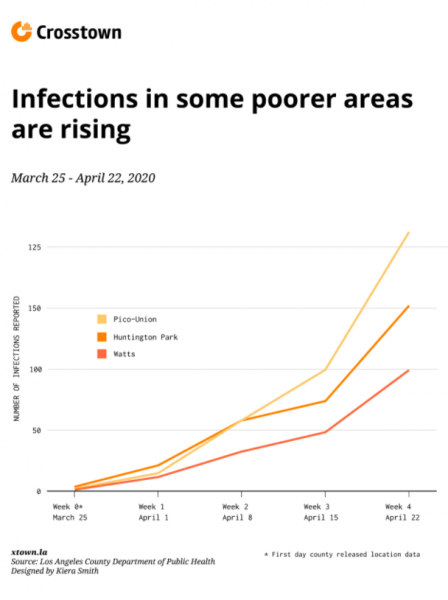

In March, when data about the spread of COVID-19 was first released, wealthy neighborhoods such as Brentwood, Bel-Air and Beverly Crest had some of the highest infection rates in Los Angeles County. Now, cases in many of those areas appear to be leveling off, while some poorer areas, including Inglewood, Historic South Central and Watts, are spiking.

This comes as coronavirus emerges as the leading cause of death in the county.

The reversal in infection rates illustrates how quickly the picture of coronavirus is shifting. As more data becomes available, it also might be exposing the degree to which wealthy communities are better prepared to weather the storm. If the current trends persist, COVID-19 will tell a troubling, if familiar, story: Los Angeles’s wealth divide is also a health divide.

When the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health began releasing data on the location of COVID-19 cases on March 25, testing kits were in short supply. Some experts speculated that wealthy areas appeared to have higher infection rates primarily because they had better access to doctors who could test them — and money to pay for the tests.

More Testing, More Cases

Now, however, access to testing has been expanded broadly, with the City of Los Angeles promising COVID-19 tests to anyone with symptoms who requests one. At the same time, wealthier residents often have a host of advantages, such as more flexible work arrangements, making it easier for them to follow stay-at-home orders. Many essential workers, though, are at the bottom end of the wage scale — working at supermarkets, assisted living facilities or on janitorial staffs — putting them at greater risk.

“If you’re a grocery worker, you might be at higher risk. These are jobs where they’re interacting with more people compared to someone like a professor, who works from home,” said Neeraj Sood, a professor at the University of Southern California’s Price School of Public Policy and a lead investigator in a pilot study examining how many Angelenos have been exposed to COVID-19. “That’s a factor that might explain why you’re seeing higher infection rates in lower-income neighborhoods,” he said.

Sood’s study, a joint project between USC and the county public health department, and which has not yet been peer reviewed, estimated that 4.1% of Los Angeles County adults may have already contracted the virus.

Lower Incomes, Rising Infections

From April 15 – 22, infection rates in Huntington Park, Pico-Union and Watts grew by over 100% each. Meanwhile, rates in Pacific Palisades, Brentwood and Calabasas stabilized, growing by only 3.1%, 8.8% and 19.2%, respectively.

According to USC’s Sood, however, this pattern could be caused by an expansion in overall testing for the virus, including more testing in low-income communities.

“You could see a larger increase [in infection rates] because there’s more testing happening now in poorer communities. That’s one potential factor,” he said.

LA County’s infection data presents just a partial picture of the virus’ path. It only tracks residents who have been tested. Officials have no way of counting people who were sick several weeks ago but were never diagnosed because testing was scarce.

According to the public health department’s website, as of April 23, there were a total of 17,508 confirmed coronavirus cases and 797 deaths. While the county releases location data on infections, location data about deaths resulting from coronavirus are not readily available.

The shift in infection rate data could be a bellwether of how the upcoming weeks will unfold, said Robynn Cox, a professor at USC’s School of Social Work and a fellow at the USC Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics. Communities that suffer from historic economic and social inequities will have higher mortality and morbidity rates and may also have a greater “likelihood of contracting the virus,” she said.

Although race information is only available for about a third of COVID-19 deaths nationwide, a worrying trend has already started to emerge. Although African Americans constitute 13% of the US population, they account for 34% of deaths caused by the virus.

In L.A. County, for example, African Americans comprise about 9% of the population but account for 16% of COVID-19 related deaths.

How we did it: We examined publicly available data from the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health on infections by neighborhood. That data is also available on our interactive map.